- 15.0Cover

- 15.1How to Read this Broadsheet

- 15.2Variations on IdiorrhythmyHeather Kai Smith

- 15.3Thresholds of ResistanceIlya Vidrin

- 15.4The Archive and UsVania Gonzalvez Rodriguez, mother tongues

- 15.5Coral VisionJess Watkin

- 15.6Casting Our Kino-Eyes Over the Collective HorizonThe Post Film Collective

- 15.7KOMQWEJWI'KASIKL 2Michelle Sylliboy

- 15.8Animating Myths to Protect EcologyPerformance RAR

- 15.9Embodying Ancestral LoveTasha Beeds, Quill Christie-Peters

- 15.10Meal of Choicesquori theodor

- 15.11The Pussy Palace Oral History ProjectElspeth Brown, Alisha Stranges

- 15.12In Search of Lost ConfidenceTonatiuh López

- 15.13En Busca de la Confianza PerdidaTonatiuh López

- 15.14Local Useful Knowledge

- 15.15Glossary

The Pussy Palace Oral History Project

Sensory Portraits of Public Sex

- Elspeth Brown

- Alisha Stranges

On September 15, 2000, five Toronto police officers raided the Pussy Palace, an exclusive bathhouse event for queer women and trans folks. Police laid several charges against two security volunteers, accusing them of violating liquor laws. Since the 1970s, oral testimony has been foundational in the preservation of queer and, more recently, trans history. Surprisingly, there has never been an oral history project about this event, the last major police raid of a queer bathhouse in Canada. From February to August of 2021, the LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory (Director: Elspeth Brown) collected thirty-six interviews with bathhouse patrons, event organizers, and community activists. Our interviews address not only the raid, but also radical sex/gender cultures in turn-of-the-21st-century Toronto.

We have since transferred the digitized collection to our collaborative partner, The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives, for long-term preservation and community access. However, a desire to connect broader publics with this history inspired us to experiment with digital research creation, circulated on social media. One form of media we produced was a duet of “sensory portraits”—animated video shorts that spotlight our narrators’ sense memories of the Palace. Our approach, which blends a queering of oral history methods with collaborative research creation and dissemination, addresses two challenges facing queer oral historians: 1) How can we make our oral histories accessible in meaningful ways, beyond simply putting them online?; and 2) How can we queer oral history interview strategies to facilitate narrators’ engagement with the past, beyond empirical recollection?

Is Anybody Listening?

Long after the work of collecting and digitizing an oral history project is complete, oral historians have no doubt asked themselves quietly, offline: is anyone actually watching, or listening to, our full-length files once we put them online? We’re thinking maybe not so much. Most people have little patience for screening long-form oral histories, or even accessing sections through indexed topics. In our work, we are trying to reach broader publics beyond academia, and, increasingly, we believe that putting interviews online, even with captions and transcripts, is not necessarily a synonym for making them “accessible.”

To address these questions of access and broader publics, we have turned to “research creation.” This relational practice has emerged over the last ten years, mostly from interdisciplinary and research-oriented artists whose work is shaped by research questions and topics familiar to those of us in the social sciences and humanities, but whose research communication strategies depart from the traditional book or journal article. As Natalie Loveless has argued, a research-creational approach asks, “What if the most powerful way to communicate the research embodied within a certain ‘chapter’ is not to write about it on a page, but to ‘write’ it through video?”11Natalie Loveless, How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 40. This question is especially apt in the context of oral history, a multimodal form of primary-source research that yields—in our case—visual, aural, and written texts in collaboration with non-academic community partners and narrators. Why not make the most of these rich sources and develop shorter-form creative works, a strategy that might succeed more in engaging the interested public?

Sight: “I see the pool. I see bubbles from the jets in the pool. I see a lot of people kind of draped and hanging out around the perimeter of the pool area, on benches. Some in the pool, some kind of parts of themselves in the pool, but outside of the pool. People are in various states of dress and undress. Someone’s walking by with a stack of towels, walking through trying to get back to the laundry room. The night is cool, and the sky is dark, and there’s a breeze.” —Karen B. K.22All sense memories are excerpted from interviews conducted by Alisha Stranges and Elio Colavito for the LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory’s Pussy Palace Oral History Project. Full interview transcripts are held at The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives, Toronto, ON.

Touch: “Smooth, wet, tile. Underneath your thighs. Along your back if you recline. Then the feeling of the tile, with water as a barrier in between, when you dunk yourself down into the warm water.” —Ange

Accessing “Queer” Historical Memory

These questions—about audience, engagement, collaboration, and the form our research takes—expose new methodological challenges in the co-creation of queer oral history. How, for example, do we interview people about their affective, somatic relationship to the past? There’s not much point in asking the Pussy Palace project narrators to answer an endless series of basic empirical questions, such as “what happened,” given that the Palace police raid was heavily reported. How, then do we encourage narrators to confide other forms of knowledge, like sense memories, in ethical and nuanced ways?

Sound: “There’s the music on the first floor. It just pounded. It sounded like a bar. It sounded like a dance club. And then you walk up the stairs, and you’re starting to hear folks having sex in the cubicles in the hallway. And you could hear different implements being engaged with. The clanking of chains, the sound of leather or flesh on flesh, and the people moaning. Clink of bottles, beers being poured out... Or cans, I think it was cans actually, being popped and poured.” —JP

Smell: “Smells like summer, smells like gin, smells like marijuana, maybe from the alley, maybe from the pool area. It feels kind of misty, kind of foggy. It feels magical, like a stolen summer night.” —Karen B. K.

After reviewing the usual literature on multi-sensory oral history and queer affect/feelings, from Paula Hamilton on sound to Ann Cvetkovich and Sara Ahmed on varying approaches to affect, emotion, and feelings, Alisha Stranges (Project Oral Historian and Collaboratory Research Manager) proposed that we investigate narrators’ sense memories of the physical space. In her view, sense memory is a form of embodied memory that embraces messier and more primal modes of communication, which cannot be exhumed through language alone. Drawing largely on her training in theatre creation and arts-based interventions in group facilitation, Alisha devised a guided meditation exercise that effectively “queers” oral history methods, inviting insights otherwise omitted from strictly empirical historical accounts. Introduced thirty minutes into each narrator’s interview, Alisha and Elio Colavito (PhD Candidate in History and Co-Oral Historian on the project) gradually refined the exercise, which, through the intentional use of breath and silence, encouraged narrators to recall the physical sensations associated with their participation in this public sex event:

I want to invite you into an exercise. It might feel a little strange, so just go with me to the best of your ability. I’ll be right there with you. Let’s try it.

Get comfortable in your chair. Placing your feet firmly on the floor...

Soften your gaze. Or, if you feel comfortable, you can even close your eyes.

Relaxing your arms, your hands, your jaw...

Just breathe...

With each inhale, allow your body to re-inhabit a specific location within the Pussy Palace. Don’t worry about which location comes to mind. The first one is the best one.

From this contemplative space, as you look around, tell me...

What can you see?

What can you hear? If the space had a sound, what would it sound like?

What does it smell like? Any lingering odours?

Imagine that some part of your body is brushing up against some part of the space. What are you touching and what are its textures?

If you could taste the space, what would its flavour be?

If you could distill this space into a single colour, what would it be?

And let that go. Opening your eyes if they’ve been closed.

Thanks for taking me there.

Between prompts, Alisha took care to leave space, creating prolonged silent pauses that interrupted the predictable rhythm of the traditional question-and-answer interview structure. Across our thirty-six interviews, each narrator delivers five to seven minutes of testimony that captures their affective and somatic engagement with the past.

Colour: “I would say dusty red, like stage curtain, like velvet curtain, dusty red.” —Terri

Taste: “Sweat, sex, lip gloss.” —T’Hayla

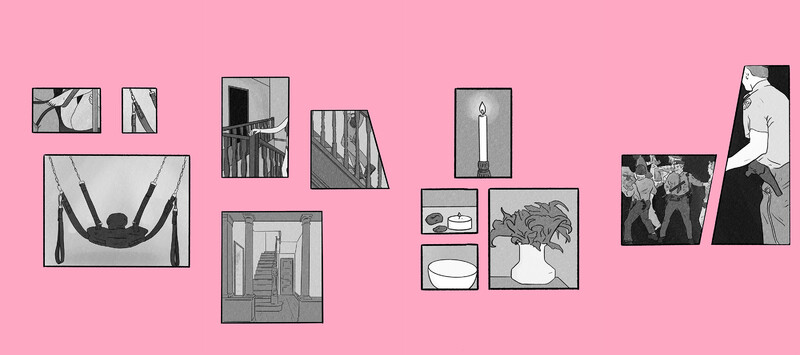

Working with these excerpts, we then produced two “sensory portraits,” video shorts that use digital art, interview audio, and original soundscapes to animate narrators’ sense memories of the Palace. The aesthetic of these video shorts evolved through our collaboration with Robin Woodward, the first project narrator we chose to feature. Creative Producer Ayo Tsalithaba began by editing together the Zoom speaker and gallery views from the sense memory exercise section of Robin’s interview, working primarily with colour and sound to communicate their vision. When we showed Robin the first cut, she requested that we remove her video footage and work only with the interview audio. In Robin’s words: “I’d be more comfortable if there was a bit less of my pandemic-winter face.”

So, Alisha and Ayo went back to the drawing board. They needed to create something visually dynamic to complement the narration, which was a challenge because we had no archival film footage or photographic evidence of the scenes Robin described. In the search for a solution, Ayo experimented with sketching and animating original digital imagery to accompany Robin’s narration, and this time Robin was thrilled with the result.

We are so grateful for Robin's audio-only request, as her feedback challenged us to stretch our creative capacity in order to settle on a solution that Robin could love and that we were proud of.

Conclusion

Sensory experiences help us access “queer” memory, enabling us to preserve the story differently. Historically, of course, queer has characterized a collection of “impossible” sexual practices, desires, and orientations that society deems excessive, unintelligible, and outside social sanction. But in redeploying “queer” as a modifier of a particular kind of memory, we can uncover in our narrators’ sensory experiences the effort to translate an “impossible” knowledge to the listener—a way of knowing and understanding past experience that unsettles us, defamiliarizes expected scripts, and communicates a story about the Pussy Palace that is otherwise intangible.

Our sense memory portraits are just one of the research creation strategies we’ve devised for this project. Others include live-action and animated video shorts on a range of topics; short audiograms; and Instagram stories. Our capstone project is an immersive digital exhibit (forthcoming fall 2023), detailing the evolution of the Palace events, the raid, and the early histories that informed this moment of radical sexual culture. The exhibit’s focal point invites users to visit nine digitally illustrated rooms within the Palace where clickable objects spark sketches of narrators and relevant interview sound bites, allowing users to engage with first-person accounts of the joys and tensions patrons experienced while attending these events. Once complete, the exhibit will live online, as a publicly accessible website. Stay tuned!

These research creation strategies seek to address the primary challenge of making our oral histories accessible in meaningful ways. To understand how we’re doing on that score, we need data about who is accessing our material, both the short versions and the long ones, and for how long. Are folks watching for thirty seconds or thirty minutes, or what? These data-driven questions are sending us down an oral history archival rabbit hole, where we are discovering a dearth of evidence-based scholarship on end-user engagement with online oral histories. But we will leave a discussion of that research for another time.

See additional content from the Pussy Palace Oral History Project online, including a video playlist of Sensory Portraits (featuring project narrators Robin Woodward and Karen B. K. Chan).

Elspeth H. Brown is Professor of History at the University of Toronto and Associate Vice-Principal Research at the University of Toronto Mississauga. Her research focuses on modern queer and trans history; the history and theory of photography; and the history of US capitalism. She is the author of Work! A Queer History of Modeling (Duke University, 2019); co-editor of “Queering Photography,” a special issue of Photography and Culture (2014); and Feeling Photography (Duke, 2014), among other books. She has published in GLQ, TSQ; Gender and History; American Quarterly; Radical History Review; Photography and Culture; Feminist Studies; Aperture; No More Potlucks, and others. She is Director of the LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory, a multi-year and public digital humanities research initiative focusing on gay, queer, and trans life stories, using new methodologies in digital history, collaborative research, and archival practice. At the University of Toronto, she is also Faculty Lead for the Critical Digital Humanities Initiative. She is an active volunteer and former President of the Board for The ArQuives.

See Connections ⤴

Alisha Stranges is a queer, community-based, and public humanities scholar, theatre creator, and performer. In January 2021, Stranges joined the Collaboratory as the Project Oral Historian for the Pussy Palace Oral History Project, where she now serves as Research Manager. Stranges holds an MA in Women and Gender Studies from the University of Toronto (2020). Her master’s research project examines the therapeutic resonances of improvised rhythm tap dance for survivors of psychological trauma. Stranges received a diploma in Theatre Performance from Humber College (2006) and spent a decade devising original plays within Toronto’s queer, independent theatre community. From 2010–15, she returned annually to Buddies in Bad Times Theatre as a teaching-artist and co-facilitator for PrideCab, an intensive training program in collective creation and performance for queer, trans, and gender variant youth. In 2019, she launched the Qu(e)erying Religion anti-Archive Project, which documents over 10 years of supportive programming for life-giving queer spirituality at the University of Toronto.

See Connections ⤴