- 15.0Cover

- 15.1How to Read this Broadsheet

- 15.2Variations on IdiorrhythmyHeather Kai Smith

- 15.3Thresholds of ResistanceIlya Vidrin

- 15.4The Archive and UsVania Gonzalvez Rodriguez, mother tongues

- 15.5Coral VisionJess Watkin

- 15.6Casting Our Kino-Eyes Over the Collective HorizonThe Post Film Collective

- 15.7KOMQWEJWI'KASIKL 2Michelle Sylliboy

- 15.8Animating Myths to Protect EcologyPerformance RAR

- 15.9Embodying Ancestral LoveTasha Beeds, Quill Christie-Peters

- 15.10Meal of Choicesquori theodor

- 15.11The Pussy Palace Oral History ProjectElspeth Brown, Alisha Stranges

- 15.12In Search of Lost ConfidenceTonatiuh López

- 15.13En Busca de la Confianza PerdidaTonatiuh López

- 15.14Local Useful Knowledge

- 15.15Glossary

The Archive and Us

Permanently Under Construction

- Vania Gonzalvez Rodriguez

- mother tongues

I wish I had a better story about how the three of us who make up mother tongues first met. I remember meeting Marina Georgiou in the kitchen corridor at work. I love her honesty. Marina can talk about very academic themes in a way that is real and accessible without being patronizing. I remember I was very impressed, and our friendship grew organically out of our desire to do something that gave us more agency than our day jobs in an institution. I felt similarly when I met Kaya Birch-Skerritt, an eloquent and in-tune person who perfectly balanced the collective.

It was Marina who had the initial idea. We wanted to do something together at the Antiuniversity Festival (London, UK), so we proposed a translation party with the Feminist Library. This was about five years ago. For that first event (Talking in Languages Translation Party, 2018), we wrote:

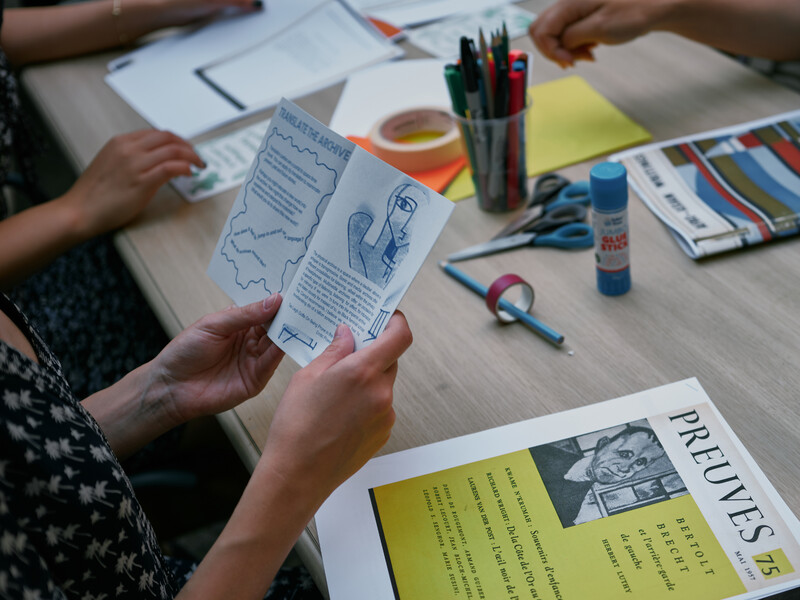

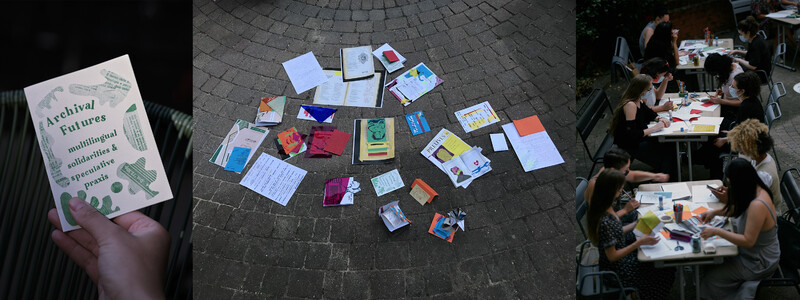

Collectively we will translate selections from zines, pamphlets, and periodicals from the Feminist Library’s special collection. Everybody is welcome! If you have an interest in translation, want to break language canons, help with opening access to a history of feminist DIY distribution, even if you don’t speak more than one language, you can still help! We will discuss issues around translation, about being part of a polyphonous community, ways of decolonizing and queering our speech and writing, etc.

During the party participants will be encouraged to select and translate extracts they find interesting and as a result the work produced collectively will be used as a resource for the Feminist Library. We will also use the library’s photocopier to make a zine out of our translations.

What Are Translation Parties?

Our first event was very popular; inevitably, we had a mix of friends and a general audience. Many of the participants were interested in translation as a formal discipline and were happy to find a space to practice their skills in a more creative way. For a majority, this was their first experience interacting with a collection. Few had the opportunity to be in a “real” archive before. As part of the workshop, we discussed these issues, the inaccessibility of certain spaces, the infrastructures, and the gatekeepers. Together with participants, we created a good atmosphere. I believe that the main element for the success of this event was the friendly approach: we hosted a party, and people were open to collaborating with us, independent of their knowledge of the collection and translation.

We’ve carried this approach forward to all our translation parties since. The workshops critically explore translation, archival, and knowledge production practices to explore how colonization and other forms of domination affect and influence our relationship to language, identity, and community.

We invite participants to translate archival materials that were selected previously for the workshop, but they are also welcome to find their own material in the archive. Participants can choose texts in one language and translate them in different ways. While translating (even using Google Translate), there are many conversations and much camaraderie. I like when people challenge the material by adding their knowledge or contextualizing certain cultural information that the original author did not. We encourage participants to be creative so that they can translate not only from text to text, but create something more abstract, some sort of illustration; people have even made small paper sculptures. Once you give them the freedom to express themselves, participants can be very imaginative. We want to make the archive alive through interaction. The result is a subverted and pluralistic archive, which is mutable rather than static.

At the end, we invite people to share their research. Together we co-produce knowledge and build a community. We believe that collective listening and dialogue are potent tools for building stronger communities, although we acknowledge that language acts in favour of certain groups. Languages have hierarchies; speaking certain languages gives us privileges, and having an accent places us in a particular position.

The workshops aim to explore and discuss how power runs throughout languages, record-keeping, and the broader landscape of the archive—and how we can intervene to reflect our way of knowing.

We are not interested in perfect translation, but in creating space for people to be playful and joyful with their languages and knowledges; in this way, we believe we are decolonizing and queering11See Mama Alto and Sue McKemmish, “Is Life a Cabaret? A Living Archive of the ‘Other,’” Curator: The Museum Journal 63, no. 4 (2020): 531–545; Yula Burin and Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski, “Sister to Sister: Developing a Black British Feminist Archival Consciousness,” Feminist Review 108, no. 1 (2014): 112–119; Kathy Carbone, “Archival Art: Memory Practices, Interventions, and Productions,” Curator: The Museum Journal 63, no. 2 (2020), 257–263; Michelle Caswell, “Inventing New Archival Imaginaries,” in Identity Palimpsests: Archiving Ethnicity in the U.S. and Canada, eds. Dominique Daniel and Amalia Levi (Sacramento, CA: Litwin Books, 2014), 35-58; and Hannah Ishmael et. al., “Locating the Black Archive,” in Communities, Archives and New Collaborative Practices, eds. Simon Popple, Andrew Prescott, and Daniel Mutibwa (Bristol: Policy Press, 2020), 207–218. our speech and writing.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In these five years, we have collaborated with many people, in different capacities, giving us opportunities to rethink our work. Last year we did our first residency, working with the Aarhus Feminist Collective and rum46 artist-run centre (also in Aarhus, Denmark). We had time to think about how we work as a collective. From practicalities like admin to well-being issues, how do we balance full-time employment, care responsibilities, and different interests with our practice as a collective, in ways that feel genuine? How do we grapple with theoretical issues around language and translation in ways that are relevant to our communities?

During our summer residency, we met other artists and collectives, and we explored ideas of change and adaptability, the natural and living archive. When we went back in autumn for the second part of the residency, we decided to do a walk in the woods. On a rainy day, we walked together to forage for mushrooms; we had conversations with participants about our bodies and our surroundings as containers of knowledges. We shared tea and biscuits while making a hanging macramé piece. Our journey took us to the sea and back through the woods. During the sharing moment, all the participants confessed to having been in the woods many times before, but acknowledged this was their first time feeling embodied there.

The residency gave us the space and time to realize that we were never just DIY—we have always worked in a Do-It-Together way. Our practice is evolving and has become more ambitious regarding relationships and collaborations. Our conversations were mainly about the possibilities of our practice. What can we do around collection/archives/language? How? Why? We want to collaborate with people who feel like home, challenge us in a pedagogical way, and are open to learning from each other. Some people who have participated in our events have become dear collaborators and friends.

We want a playful practice that brings joy—and, to some degree, hope—to the people we work with, and us too.

This year we have already been back in Aarhus to work on a new art project with platform Sigrids Stue in the neighbourhood of Gellerup. We met the artists running the space last year during our residency. This interaction introduced many new questions into our practice. How can we bring sustainability to our relationships? What can we offer as visitors?

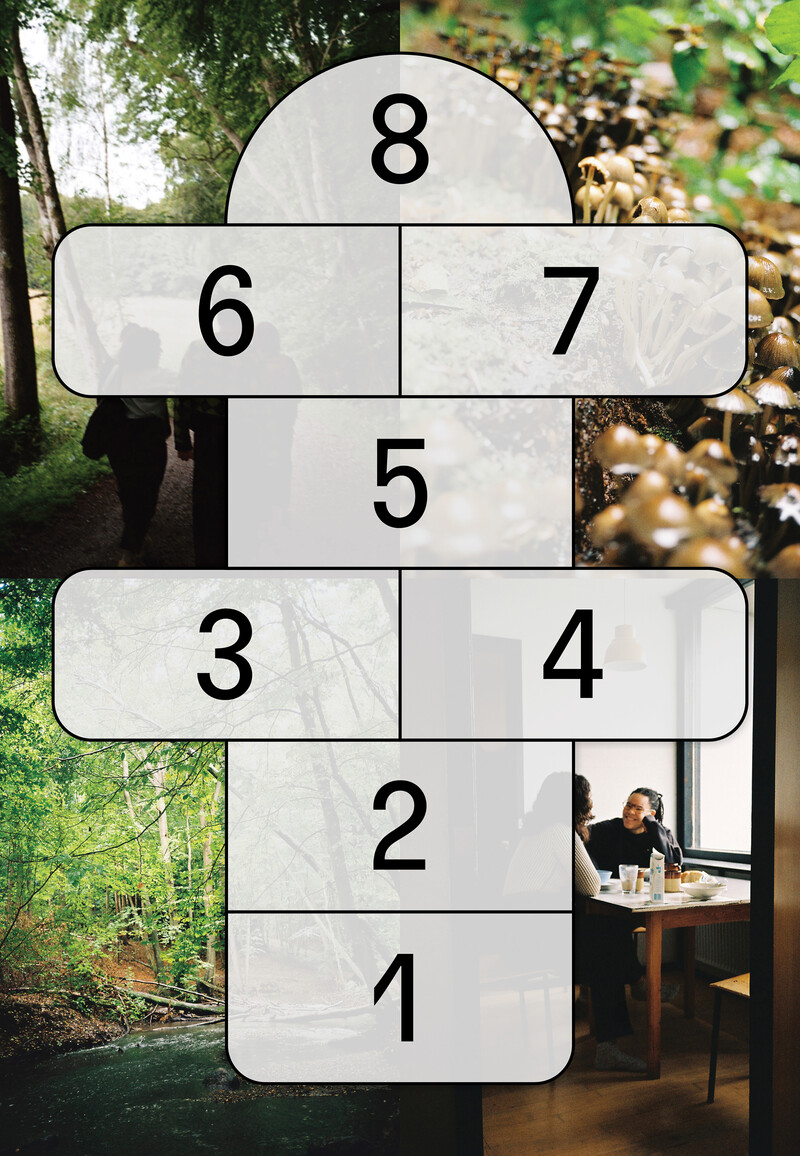

We hope to continue to build and deepen our network in order to create a more intentional art ecosystem, one that does not replicate hierarchies of power. I envision Rayuela (hopscotch) as an exercise for doing this.

Rayuela

I want to invite our readers to play Rayuela to recall some past reflections about our practice. You don't need to read this in the usual way; you are allowed to move around, and jump in and out through words.

8. Understand one another

7. Search for healing

6. Build solidarity

5. Radicalize the archive

4. Fail to translate

3. Help us fill the gaps in our memory

2. Decentralize your approach

1. Challenge homogenization

8. Translating languages is not just about speaking another language, but also about understanding one another. Translation as tactile. Translation as decolonial. Translation as creation.22Conversation with Marina Georgiou, 2023.

7. Our translation parties provide a space for building solidarity: in particular, the multilingual nature of the attendees offers exciting possibilities for forming transnational solidarities. They also provide a space for joy, which feminists are increasingly coming to value as an essential component of building sustainable movements.33Emily Beswick, “Cartographies of Queer Diaspora: Jin Meiling and Mary Jean Chan,” 2020, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bn7HQt-dpd6CZ0-zFHV-kqrq0r4e0hsL/view?usp=sharing.

6. Solidarity is multilingual; we translate texts and materials not only with knowledge of the language but the cultural context, and we incorporate certain practices in search of healing. We challenge the idea of traditional archives and their past, and we imagine a future of other stories and histories that are celebrated.

5. The translation parties contributed to a radical archival environment in which positions of authority (such as facilitator or archivist) were relinquished in favour of open dialogue, heterogenous knowledge production and community building.44Kaya Birch-Skerritt, “How Can an Archive be Creative?,” 2021, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ic6-H_BAEXqynuEiVw4GdcHgZ-NV_ja5/view.

4. In mother tongues’s regular translation parties, the collective intertwines their praxis of “failure in translation” with feminist praxes—of consciousness-raising, building solidarity, and producing documentation. The process of decolonizing and feminist theory and praxis opens up space to imagine alternative understandings of language, which embrace multilingualism and “unmasterability.”55Beswick, “Cartographies of Queer Diaspora,” 2020.

3. Have you been to one of our events? Please send us your reflections to mothertonguescollective [at ] gmail [dot] com.

2. We try to take a decentralized approach in terms of the projects we do because we are more interested in sharing knowledge and reclaiming agency. Our workshops are all about collaboration and creating communal spaces for experimentation and creation. Interaction is key to explore languages and creating spaces for different people.

1. The danger of homogenization. We developed our translation parties out of a desire to explore the legacies of colonial linguistic homogeneity, its affective consequences, and the ways that archives are implicated in both the suppression and preservation of marginalized histories. Our involvement with autonomous archives was a refusal of the colonial archival paradigm and its resistance against an embodied, participatory, and non-extractive approach to handling and interpreting of its records and collections.66Birch-Skerritt, “How Can An Archive be Creative?,” 2021.

Written by Vania Gonzalvez Rodriguez in conversation with Kaya Birch-Skerritt and Marina Georgiou.

Vania Gonzalvez Rodriguez is a Bolivian artist and cultural producer based in London, UK. Vania's practice explores languages, memory, grief, and archives. Vania is interested in how ritual and embodied knowledges can be tools for healing. Vania works at the Barbican Centre as a learning curator.

See Connections ⤴

mother tongues is a transdisciplinary research-led project applying decolonial, feminist, and queer pedagogies to explore language and identity. Their practice responds to language’s impact on personal and collective empowerment and aims to democratize archival collections and knowledge production. mother tongues is formed collaboratively by Kaya Birch-Skerritt, Marina Georgiou, and Vania Gonzalvez; they collaborate with artists, curators, and researchers, and are based in London, UK.

See Connections ⤴