- 7.2.0Cover

- 7.2.1tl;dr part 2Editorial

- 7.2.2Proposition 1: HandsIvetta Sunyoung Kang

- 7.2.3Breaking with the PastJarrett Robert Rose

- 7.2.4On Solar FuturesImre Szeman

- 7.2.5technology of careMirusha Yogarajah

- 7.2.6W.E.I.R.D.: EmergencyNicola Privato

- 7.2.7COVID-19 ARMitchell Akiyama

- 7.2.8XKara Ditte Hansen, cheyanne turions

- 7.2.9The Ill-Fated Class of 2020Alex Cameron

- 7.2.10This Text is a MonumentMark Dudiak

- 7.2.11Endurance Is Not ResistanceOlivia Klevorn

- 7.2.12Pandemic, Time for a Transversal Political ImaginationAli Ahadi

- 7.2.13Wake Work and the Coronavirus PandemicBeverly Bain

- 7.2.14When your people are sickJayda Marley

- 7.2.15MetanoiaLynn Hutchinson Lee

- 7.2.16“the future is ritual”shaina sarah isles evero fedelin agbayani

- 7.2.17Essential Work = Essential WorkerEmily Cadotte

- 7.2.18New HeuristicsJesse LeCavalier

- 7.2.19(séro)TROPICAL(e)Gian Cruz

Metanoia

- Lynn Hutchinson Lee

On Representing the Crisis: A Response to Metanoia

Laura Tibi

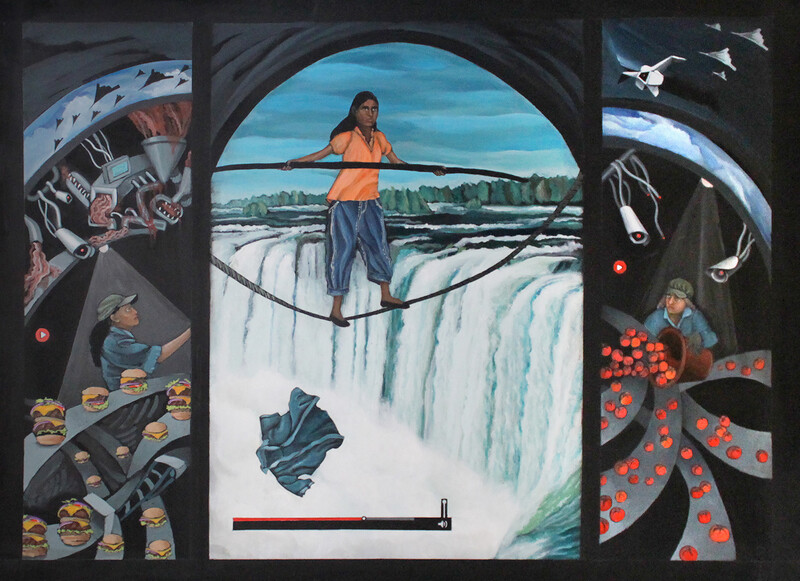

As the COVID-19 crisis lays bare capitalism’s innate injustices and reliance on the exploitation of enslaved peoples, immigrants, prisoners, and undervalued workers, I cannot help but wonder: What will become of our society? Will our apathy persist, or will the virus finally push us to take responsibility, acknowledge our role as passive perpetrators, and become critical, accountable citizens? Despite the nauseating bouts of performative activism and empty gestures of gratitude that the virus has unleashed, there seems to be a resurgent commitment to issues of class and solidarity gaining traction. Lynn Hutchinson Lee’s paintings evocatively capture the shifting moral impulse of our era by mobilizing a historical visual idiom to represent a contemporary problem. In doing so, she reminds us that the crisis is not an empirically new phenomenon, but rather an explosive accumulation of centuries of violence, dependency, and exploitation.

The triptych composition she adopts, typically found in altarpieces, is especially fitting considering the biblical proportion of the events unfolding. (While moralizing narratives around the virus run rampant, we must remember it is a non-living being with no religious convictions or ethical commitments.) Formally and thematically, Hutchinson Lee’s paintings are more reminiscent of the social realist style found in early- to mid- twentieth century Mexican murals—those of Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco—than of religious painting. Precarious labour: cook/ harvest/ balance notably picks up on the motif of the factory worker, much like Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural, who toils at a never-ending assembly line to barely make ends meet. But unlike the industrious, collaborative mood of Rivera’s rugged labourers, Hutchinson Lee’s workers are isolated and detached, signifying what Karl Marx referred to in Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 as Entfremdung or capitalist alienation. The menacing presence of overhead video surveillance reminds us that, despite the isolation of Hutchinson Lee’s workers, they are not completely alone, but in observed seclusion. On the one hand, the cameras act as a stand-in for supervision; on the other, they represent a more generalized, now exacerbated, panoptic surveillance in service of permanent and automated control.11Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books), 201–2. In the central panel, we see the figure of a woman of colour balancing on a rope suspended above the sublime backdrop of waterfalls—the artist’s personification of the precarious conditions of migrant workers throughout the Niagara region, and the disproportionate effects of the current crisis on migrant workers from across the Global South.

If precarious labour represents the dangers of working amid a pandemic, then slaughter/ drown/ serve/ eat points to its political correlative: the longue durée of overproduction and mass consumption. In the latter tableau, the precarity of industrial work is framed as a distant, Othered place: always elsewhere and never that which immediately concerns us. We are instead supplied with an abstraction of labour through intentionally irrational spaces and dizzying perspectival logics. The visual legibility and utopian promise of social realism is now supplanted by a hellish Boschian dystopia complete with flooded streets, floating pigs, and a disturbing display of glut. What I find most unsettling is the untouched feast in the central panel. Upon closer inspection, we see a scorpion served on a bed of red cabbage and a rat garnished with lettuce. Equally grotesque are the anthropomorphic dogs crawling in the far-left corner. By injecting such surreal, repulsive images into a portrait of wealth and privilege, Hutchinson Lee emphasizes the obscenity of social inequality. When viewed next to precarious labour, it becomes clear that the current crisis is part of a longstanding economic, social, political, and environmental problem that is endemic to capitalism. The subtle incorporation of pause and play buttons evokes questions of historicity, temporality, and duration. And while we all want to know when this nightmare will end, what we really need to consider is: How will we otherwise move forward? This may not be the last pandemic we experience in our lifetimes, but if we ever want to undo a system premised on centuries of violence and injustice, we need, at the very least, to implement more critical, tactical, and active approaches. We can begin this lengthy but necessary process of unlearning, unbecoming, and undoing by representing and understanding the crisis through and against history.

See Connections ⤴

Laura Tibi is an art historian and Educator-in-Residence at the Blackwood.

See Connections ⤴