- 02.0Cover

- 02.11:10000Dana Prieto

- 02.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 02.3Fort McMurrayMatt Hern, Am Johal

- 02.4Clouds and Complexity: Viewing the Earth from SpaceKent Moore

- 02.5A memory, an ideal, a propositionKarolina Sobecka

- 02.6Alterlife and Decolonial Chemical RelationsMichelle Murphy

- 02.7ᔥᑲᑲᒥᒃᐌ ᑭᑐ

Shkakamikwe Kido

It Comes Through The LandNatasha Naveau - 02.8St. Lawrence CrossingSydney Hart

- 02.9Sister WaterAndrea Muehlebach

- 02.10Changing TogetherStanka Radović

- 02.11The Right to ChargeFraser McCallum

- 02.12What is The Market?D.T. Cochrane

- 02.13Canada’s Waste FlowMyra J. Hird, Canada's Waste Flow

- 02.14A Brief History of Lake Ontario and Lake Ontario WaterkeeperHarvey Shear

- 02.15Reflecting on Sustainable Transportation

The Climate Change Project, City of Mississauga

- 02.16Local Useful Knowledge: Resources, Research, Initiatives

- 02.17Glossary

What is The Market?

- D.T. Cochrane

“Leave it to The Market.”

We frequently hear variants of this refrain from pundits and politicians: following the immutable laws of supply and demand, the Market will generate the best possible outcome. However, this mythical Free Market does not describe how actual markets function. Rhetoric about the Market misrepresents both the innumerable structures that support and maintain them,11See Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001). and the necessary interventions to prevent and correct their associated harms, such as worsening inequality and environmental degradation.

The discipline of economics has normalized structures of unequal exchange in its formal models, where unencumbered exchange among equal individuals generates an outcome deemed both just and efficient. Whether market participants are twenty-somethings newly living on their own or the Coca-Cola corporation, the theory tells us that they both enter the market as atomistic utility maximizers, meaning neither has any power within the market and both are driven by self-serving desire. From the competition between these powerless equals, prices for all goods emerges. Despite the prevalence of indisputable corporate power, it is absent from the theory. This theory is so dominant in economics that it is rarely named, although it is often called “neoclassical,” or more descriptively, “marginalist.”22For a critical analysis of contemporary, mainstream economic theory, see Ian Hudson and Robert J. Chernomas, Economics in the Twenty-First Century: A Critical Perspective (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016).

Much of the focus of contemporary economics is on trade-offs: how much of this thing would you give up for that thing? The Market is the place where individuals make such trade-offs. I trade my labour for these goods. I trade this food for that service. On and on and on. Within the marginalist framework, individuals—assumed to be the best judges of their own well-being—will continue making trade-offs at the margin until the achievement of what economists call Pareto optimality, after one of marginalism’s foundational thinkers, Vilfredo Pareto. At the Pareto optimum, no one can be any better off without making someone else worse off. While you might want more corn, you aren’t willing to give up any of your gold necklaces to get it. When we achieve this state, we are, the theorists tell us, in an equilibrium where everyone is as well off as possible.

The concept of equilibrium is the theoretical counterpart to the margin. Trade among individuals rebalances the system until a utility-maximizing equilibrium is achieved. If there is some sort of disturbance to the system, such as a new technology or a new source of inputs, then markets will redistribute things until we achieve a new equilibrium.

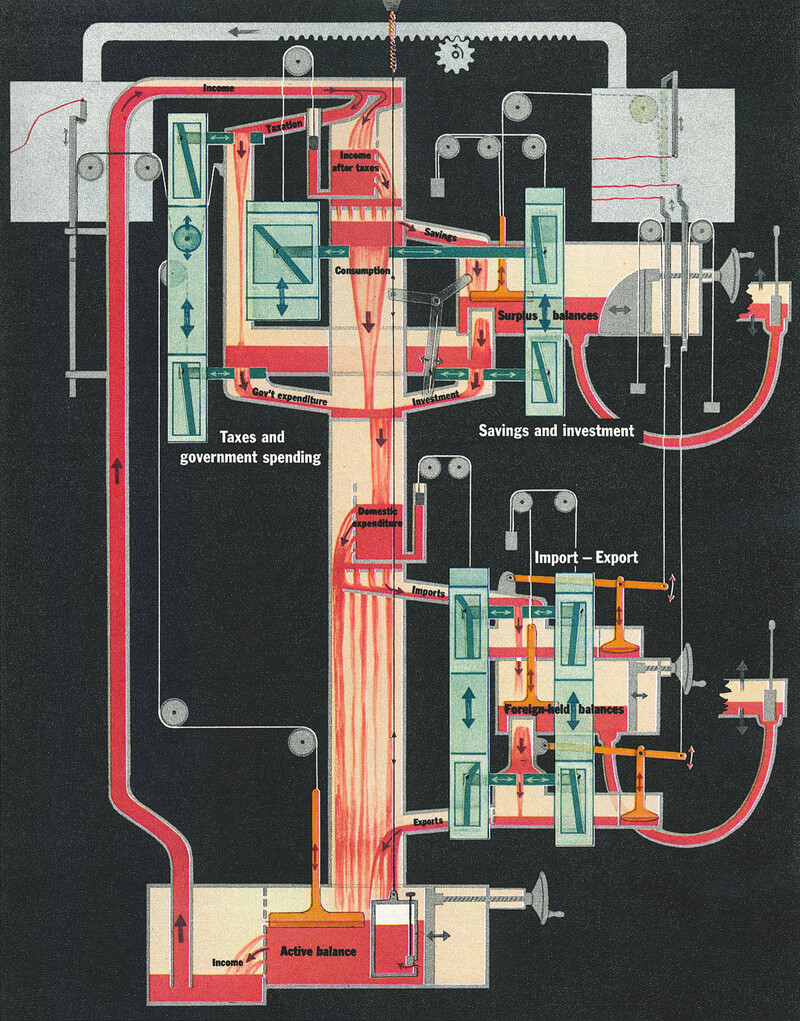

To illustrate this equilibrating process, Irving Fisher, another of marginalism’s foundational thinkers, used a hydraulic model.33See William C. Brainard and Herbert E. Scarf, “How to Compute Equilibrium Prices in 1891,” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 64, no. 1 (2005): 57–83. He connected a series of irregularly shaped cisterns together with hoses and rods to visualize how goods get distributed and redistributed among consumers. With the addition and subtraction of water from the system, a new equilibrium would be established where the utility of each consumer (container) was maximized.

While an ingenious visualization of the marginalist theory of the Market, Fisher’s hydraulic model also unwittingly expresses how disconnected this theory is from actual markets. The water in Fisher’s model performs its equilibrium-establishing role because it is isolated from the water cycle. Actual, globally connected water systems are far-from-equilibrium, driven by the Earth’s atmospheric heat engine.44A. Kleidon, “A Basic Introduction to the Thermodynamics of the Earth System Far From Equilibrium and Maximum Entropy Production,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365, no. 1545 (2010): 1303–15, doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0310. Melting glaciers, falling rain, and rising steam participate in the temperature differentials that keep the Earth’s materials in geochemical circulation.

The global economy is also a far-from-equilibrium system, and markets are part of driving the social transformations that keep it out of equilibrium. Consider the cement market. Cement is one of the world’s most important building materials. The most common variety, Portland cement, was developed in the mid-nineteenth century, and its consistent production techniques make it a highly standardized global commodity. At the same time, cement is bulky and expensive to transport, which keeps cement markets relatively local. Cement plants are costly to build, have large productive capacities, and can operative efficiently for a long time. This means one plant can satisfy a lot of demand, while the costs of entering a market are very high.55For more on cement markets, see Hervé Dumez and Alain Jeunemaître, Understanding and Regulating the Market at a Time of Globalization: The Case of the Cement Industry (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 1999).

One effect of this local-global tension is that cement prices diverge based on whether a market can be served by coastal transportation. Cement markets are strongly connected to both the pace and location of urbanization. The supplier to a land-locked city that is growing too slowly to entice new cement plants has more price-control than one in a coastal city large enough to warrant multiple plants.

The geographical and geological realities of cement markets have led to many small, local producers, with a handful of global giants. One of those giants is CRH plc, which owns the cement plant in Mississauga. Previously, the plant was owned by another global cement giant, Holcim Ltd., which sold the plant as part of a 2015 merger with yet another giant, Lafarge SA. The sale of the Mississauga plant, along with Holcim’s other Canadian assets, was in response to “competition concerns” expressed by Canada’s Competition Bureau. According to the bureau, the sale to CRH served to “preserve competition in the supply of cement and related products throughout Canada.”

The Competition Bureau exists because mythical Free Markets do not. High concentration of ownership in the cement industry would be worrisome for the users of cement, so the Bureau polices the redistribution of market power that occurs with mergers like that between Holcim and Lafarge. The regulations enforced by the Competition Bureau are just one set among many that bear on the cement market. Others include building codes that regulate material uses for reasons of health and safety. Yet others will pertain to carbon emissions, which are very high for the cement industry. All of these regulations exist because economies affect and are affected by the rest of society.

There is no Market to which things may simply be left. Because markets are always subsumed and penetrated by innumerable social relations, they will always require interventions and regulations. This will in turn provoke further changes, shifting the conditions of supply and demand—and thus altering prices.

A favoured phrase of the marginalists is ceteris paribus: all else being equal. Marginalist theory works by imagining that each small change has only an isolated effect, and the system easily settles back into equilibrium, as in Fisher’s hydraulic model. However, like moving water molecules, market transactions are themselves forces of change with effects that ripple outward, transforming other markets, altering desires, shifting prices, redistributing incomes across spatial and temporal scales. These ripples then amplify and contract, feeding back into the originating market. Ceteris is thus never paribus; economies are always far-from-equilibrium, and actual markets bear no resemblance to the Market.

Part two of a serial column on the fundamental concepts of commerce and exchange as driving forces that propel climate change.

Issue 01:

What is the Economy?

Issue 02: What is the Market?

Issue 03:

What is Growth?

Issue 04:

What is Innovation?

Issue 05:

What is a Price?

Issue 06:

What is Value?

D.T. Cochrane is an economist currently living in Peterborough, Canada with his partner and two children. He is an economic research consultant with the Blackwood Gallery at the University of Toronto Mississauga and the Indigenous Network on Economies and Trade. He is a postdoctoral fellow in "Innovation and Rentiership" at York University with Dr. Kean Birch. He is also a researcher with Canadians for Tax Fairness, where he works on issues of corporate power and inequality. D.T.’s central interest is the translation of qualities into quantities, and the ways that process and its outputs participate in the many struggles to remake our worlds.

See Connections ⤴