Migratory Passages confronts the politics of sea space and migration, figuring water as both a lifeline and a dangerous or unknowable threat. The series brings together artists and collectives to address the oppressive restrictions around maritime migration; the policing and “illegalizing” of migrants and refugees; the ambiguous territorialization of oceanographic space; the risks associated with irregular border crossing; the personification and mythologization of water sources and bodies; and the spectropolitics surrounding the history and legacy of colonialism across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Titled Theme for the Cross, Yassine Rachidi’s image tells a narrative of a Tunisian man, Mohsen Lihidheb (Momo), who wanders the coast of Zarzis in the southeast of Tunisia, collecting the lost objects of migrants, or harragas.1 What initially began as a voluntary beach cleanup quickly took a sociopolitical turn as Momo came to find hundreds of thousands of migrants’ shoes, clothes, and letters stashed in bottles, which he uses to locate their identity and write poems in tribute to their memory.

Taken in Momo’s garden during a joint visit with Rachidi, Sasha Davai’s photograph is a kind of trace or spectre, to borrow from Derrida, that “is both visible and invisible, both phenomenal and nonphenomenal.”2 The Arabic graffiti on the wall reads, “why is the sea laughing,” a reference to a poem by the Egyptian poet and critic, Naguib Surour. The presence of the migrants’ personal belongings set against Surour’s wistful verse serves as an eerie reminder of the lives lost at sea, while also speaking to the longue durée of colonialism in the Maghreb, which continues to haunt the present. Davai’s image further reminds us of the blessed/haunted binary as it relates to water: water as a means of purification and source of rebirth, and water as a sublime force of nature haunted by the ghosts of harragas.

In a similar vein, Jumana Emil Abboud’s work, titled The Dig, invokes blessed and haunted water sites via Palestinian folklore. Activated by spirits, demons, angels, and jinn,3 the water sourced from these sites is believed to hold curative and transformative powers. Water from these sites is handled with prudence and care, with the wellbeing of nature entwined with human health and spiritual protection. By employing anthropological and ethnographic methodologies and calling on the memories of elders, Abboud maps out sacred wells, oases, streams, and springs cited in Palestinian folktales. After locating them and gathering detailed research notes, drawings, photographs, and maps, she develops imagistic collages, animating and preserving Palestinian tales and rituals and reclaiming the Indigenous history of the landscape.

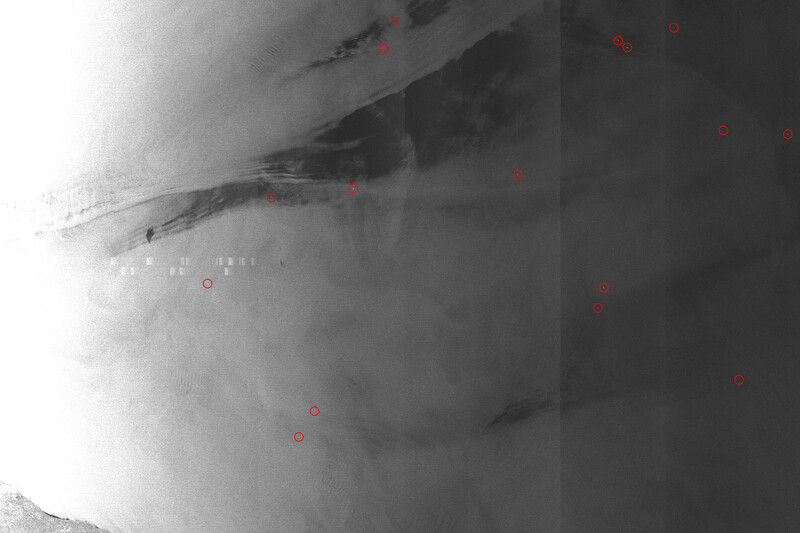

Forensic Oceanography’s research also relies on a kind of oral history as they combine testimony with images and data collected from the Mediterranean Sea in order to reconstruct the effects of militarized border control. Using footage taken by the European Space Agency’s Envisat satellite, Liquid Traces depicts a migrants’ boat caught on a portion of the Strait of Sicily between the coast of Libya (lower left) and Malta (upper portion).4Although satellite images are typically weaponized for the surveilling, policing, and “illegalizing” of migrants, Forensic Oceanography appropriates and repurposes them as evidence of state abandonment and neglect. They describe this technique of reading images captured by remote-sensing devices in opposition to the desires of migration management regimes as a “disobedient gaze.”5 By deploying the very technologies of surveillance used against migrants, they refocus our attention back onto the cruelty of border enforcement, reminding us of the actors involved and the neocolonial regimes they perpetuate.

Popular news coverage of the migrant crisis is oversaturated with images of migrants and refugees in precarious conditions. The images in Migratory Passages intentionally reject the dehumanizing depiction and commodification of pain and trauma, privileging melancholic ruminations, diagrammatic reconstructions, and folkloric allusions over explicit, brutal imagery. In so doing, they invite us to critique and challenge the violently differential logic of necropolitics, underpinned by capitalism and fuelled by mainstream media. As Hito Steyerl stated, “a growing number of unmoored and floating images corresponds to a growing number of disenfranchised, invisible, or even disappeared and missing people.”6 Given the uneven relationship between Global North actors and Global South communities, the series asks: What constitutes responsible mediation? How do we chart colonial history against capitalist institutions of violence? How do we account for regional and cultural specificity under displacement? And where does the large and critical diasporic space come into play? Through biographical, narrative, cartographic, and imagistic strategies of representation, Migratory Passages aims to generate more responsible and thoughtful discourse around crises of borders and nationalisms in the postcolonial theatre of MENA, harkening back to water as a transformative entity and risky passageway.

Migratory Passages

Burning Glass, Reading Stone is collectively curated by current and recent Blackwood Gallery staff

Installation Views

Reader-in-Residence

Interpretive Video

Educator-in-Residence Laura Tibi leads a tour of Migratory Passages on University of Toronto Mississauga campus.

- Artists

- Yassine Rachidi

- Sasha Davai (Alexandra Lapina)

- Jumana Emil Abboud

- Forensic Oceanography

- Charles Heller

- Lorenzo Pezzani

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently closed.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.