- 00.0Cover & EditorialAnchi Lin, Letters & Handshakes

- 00.1Care and Dying: Albert Banerjee in Conversation with Steven EastwoodAlbert Banerjee, Steven Eastwood

- 00.2Care as InfrastructureAi-jen Poo, Letters & Handshakes

- 00.3covering, distribution, cleaning my instrumentRadiodress

- 00.4Dilemmas of CareEmma Dowling

- 00.5CareForceMarisa Morán Jahn

- 00.6Antinomies of Self-CareLauren Fournier, Lynx Sainte-Marie, Sarah Sharma

- 00.7Other forms of convivialityPark McArthur, Constantina Zavitsanos

- 00.8It Takes Work to Get the Natural LookChloé Roubert, Gemma Savio

- 00.9Water is LifeOnaman Collective

- 00.10Seniors' Advocacy in OntarioCare Watch, Kassandra Hangdaan

- 00.11In Sickness and StudyCarolyn Lazard

- 00.12Shut. Muskrat. DownLabrador Land Protectors

Dilemmas of Care

- Emma Dowling

“Happiness is having someone to care for.” Stenciled in intricate Edwardian curlicue, this phrase frames a picture of a young girl in an apron, a colourful array of flowers at her feet. The toy ironing board on which this is imprinted appears in a collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood. A plaque informs young visitors that this toy was produced between 1970 and 1980 and was part of a set that also included a stove, sink, and cookery—everything, according to the museum label, “you would need to copy the work that grown-ups do in the kitchen.” Yet the feminized imaginary conjured up by the picture of the girl, the pastel colours, and the floral motif suggest that this is not about the household chores of adults in general but about the work of women in particular, for whom care is not presented as an obligation to fulfill but as the core of happiness in life. Positioning the opportunity to care as the key to female happiness aligns the needs and wishes of others with a sense of meaning and worth for one’s self.

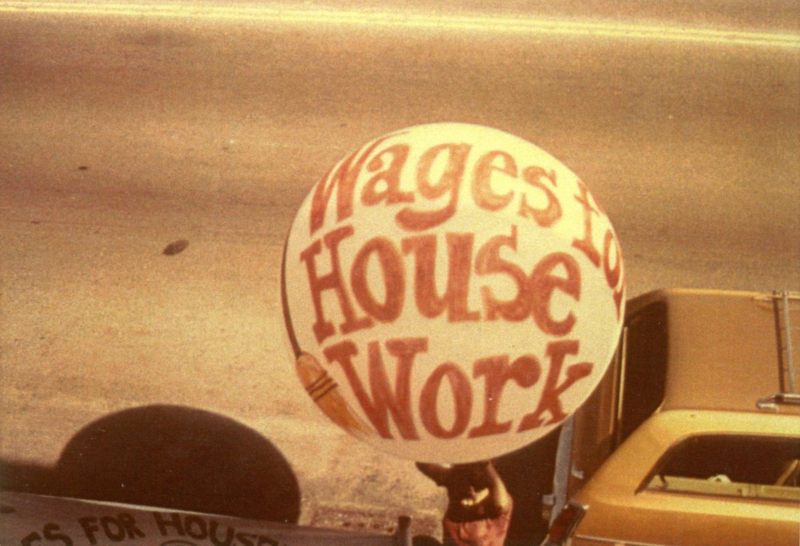

Feminized care work has not merely involved cooking, cleaning, and ironing in the household, but also encompasses the affective labour of tending to the emotional needs of those within and outside the household. Against the sanitized view of caring as bliss, the material realities of care work are more complex. Despite some uncoupling of care from gender as a result of feminist struggles, the global burden of caring responsibilities still disproportionately falls on women’s shoulders—even as more women have entered the paid workforce. The market’s incursions into ever more areas of social life has entrenched a highly stratified care sector, where class, gender, race, and citizenship and migration status are intersecting determinants of who does the mostly underpaid, increasingly precarious, and frequently arduous work of tending to others.

Nonetheless, the suggestion of a causal link between “happiness” and “care” expresses a basic dilemma of care: even if care work remains unequally distributed, or is performed under conditions of duress with insufficient resources, caring is fundamental to what is meaningful about social life. Care, moreover, comes with responsibilities that cannot easily be refused—for needs that cannot simply be ignored.11Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012).

“Take care,” we say to a friend as time spent together comes to an end. “Take care” is not just advice, however: it is an imperative—to slow down and take time to be attentive to oneself, to others, to one’s surroundings. The word “care” stems from the Old English caru, meaning “sorrow, anxiety and grief,” or “burdens of the mind.” Think of the images invoked by the term “care-free,” of being without a worry in the world. The etymology of “care” is distinct from the Latin cura, meaning to look after, or ensure the well-being of, something or someone. What a fine line there can be, though, between caring and fretting, between ensuring one’s own well-being and someone else’s, and between being anxious or worried about oneself or someone else, or even about the state of world. In a way, the tension between caru and cura is what is expressed in the Marxian understanding of labour’s double-edged freedom—the freedom to sell our labour power rests upon an absence of freedom derived from a lack of access to subsistence, which determines our need to labour for an income. Seen this way, our impulse to care can come from fear as much as from a sense of affection and connection.

Care work is the lifeblood of our social and economic system, yet, on the whole, we show little appreciation of just how valuable care work is: it provides the very conditions for us to live any kind of life at all, let alone the conditions to create economic value. Although a significant amount of caring is done outside of what we tend to think of as the economy—within homes and families or other personal relationships—caring is no personal, private matter. Care work—how it is done, by whom, under what circumstances, and to what end—is of concern to all of us. Few stop, however, to ask why it is that nurses, teachers, and child-minders, despite their immensely important work, are often some of the lowest paid workers. A satisfactory answer must turn the usual way of thinking on its head: it is not because care work is worth little that it has not been sufficiently valued; rather, the externalization of the cost of care work is the basis on which the system of profit-making is built. Care is offloaded onto the unpaid realms of homes and communities, of over-time, of going beyond our duties, of rolling up our sleeves and taking responsibility—precisely because, well, we care.22Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James, The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1972).Here lurks the ur-dilemma of care work’s cathectic bind in the contemporary political economy, a dilemma exacerbated by the double-squeeze of austerity and privatization that cuts people’s already frayed ability to care for themselves and each other, further deepening the wound of capitalism’s ongoing crisis of care.33Nancy Fraser, “Contradictions of Capital and Care,” New Left Review 100 (2016): 99–117; Ruth Pearson and Diane Elson, “Transcending the Impact of the Financial Crisis in the United Kingdom: Towards Plan F—A Feminist Economic Strategy,” Feminist Review 109, no. 1 (2015): 8–30.

Care, then, is at the heart of capitalism, despite the fact that it appears on the whole to be an un-caring system. There has been much public debate over how the global financial crisis, for example, was caused by a lack of care: bankers out for a big and fast buck, in cahoots with politicians who turned a blind eye to rampant speculation and the lack of regulation in the financial sector. When people seeking refuge from war and conflict drown while attempting hazardous sea crossings, some say that those providing help should not do so, lest this motivate more refugees to come—a demonstrative refusal of care is advocated as a form of political deterrence. Events like this are a stark reminder of a very real stratification of care made up of both hierarchies as well as boundaries. Together such boundaries and hierarchies determine just exactly who is afforded what kind of care and on what basis. At times, though, when populations are mobilized to care, their care is refracted through spectacularized outrage that feeds off what has been termed “poverty pornography,” with its images of hunger, disease, and strife.44Ratimi Sankore, “Behind the Image: Poverty and Development Pornography,” Pambazuka News, 21 April 2005, http://www.pambazuka.org/governance/behind-image-poverty-and-development-pornography.Inciting patronage, this care is infantilizing and victimizing; it reinscribes domination, reproduces inequality, and abrogates its recipients of their agency, stake, and voice.

Even the discourse of self-care now exudes a “tactical polyvalence”55Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, trans. Robert Hurley (London: Penguin, 1976), 154.as it travels from the ranks of insubordinate Black feminists66Audre Lorde, A Burst of Light: Essays (Ann Arbor, MI: Firebrand Books, 1988).and radical philosophers77Michel Foucault, “The Ethics of the Concern for the Self as a Practice of Freedom,” in Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, ed. Paul Rabinow (New York: The New Press), 281–301.to self-help guides and diet ads, heavy with self-importance. Where once self-care was conceived as necessary to resist a system stacked against the survival of those it didn’t want or need, self-care’s battle-cry is now the transmission belt for financialized capitalism’s most recent attack on what is left of collective solidarity and public welfare: Take care of yourself, because nobody else will!, the billboards warn, as they offer an array of lifestyles, products, and mindsets that promise—if purchased—to ward off our fears.

If the task is to understand care as an enabling force, perhaps even as a basis for politics, we must navigate the contemporary dilemmas of care. Care is a complex relationship, and caring is an affective disposition that can be both oppressive and liberatory. Practices of care have an ethical dimension that has to do with how we value ourselves and others—as well as the natural environment that makes planetary life possible. This is not purely ideational: expressed in material, embodied practices, and inserted into the capital relation, practices of care become sites of struggle over the means to live well.

What would a radical conception of collective care look like for our time? One that can transform the power relations that reinforce care inequalities? One that can withstand the imperative to align one’s self-care needs with the demands of self-optimization in the service of financialized capitalism? One that offers a real alternative to the temptations of a new “caring capitalism”88Emily Barman, Caring Capitalism: The Meaning and Measure of Social Value (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016).or “compassionate” capitalism in which an entrepreneurial hand can find its ethical glove in “doing well by doing good,”99Matthew Bishop and Michael Green, The Road from Ruin: How to Revive Capitalism and Put America Back on Top (Danvers, MA: Crown Business, 2010).making money out of the efforts of communities to address their ongoing care crisis as they put their unpaid, volunteer labour to work in order to fill the gaps in existing welfare provision?

Will the robots marching towards us lend us a helping hand? Our collective fantasies about robotics seem to oscillate between two equally fallacious pitfalls: disparaging techno-skepticism and willful techno-optimism. On the one hand, our fears conjure up a dystopian landscape of algorithmic anomie of unhappy loners whose social relationships are replaced by robotic interaction.1010Michele Hanson, “Robot Carers for the Elderly Are ‘Another Way of Dying even More Miserably’,” The Guardian, 14 March 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/mar/14/robot-carers-for-elderly-people-are-another-way-of-dying-even-more-miserably.On the other hand (and at times no less eerie) is the utopian polemic for a world without work, where machines do everything humans don’t like to do, so that people can spend their time caring for one another in meaningful ways.1111Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World without Work (New York: Verso, 2015). Yet technology is of course always enabled or constrained by the social, political, and economic power relations it exists within. The key question here is: to what extent do technological developments reinforce and entrench existing inequalities, and to what extent might they be utilized to overcome them?

The politics of care is a politics of dilemmas. Care work is systematically undervalued, yet it is essential to the functioning of society. The more that capitalism undermines our capacities to care for ourselves and one another, the more the crisis intensifies. We know that simply calling on everyone to “care more” does not address the structural inequalities that impose the burden of care on some shoulders more than others, while also marginalizing the voices of those doing the care, as well as those in most need. The demand, then, is not for a politics against care, but a politics that acknowledges and augments the value of care. Yet we should be cautious about framing the value of care in conventional economic terms. Doing so risks confining the politics of care to the register of money, inadvertently preparing the ground for the further marketization and thus privatization of care. Can we think instead about how to drill down into the concrete materiality of care practices in order to truly give value to care? How might we provide and democratize the means, time, and capacities for care as we struggle to find a way out of the crisis?

See Connections ⤴