- 10.0Cover

- 10.1Ghost PopulationsInes Doujak

- 10.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 10.3BluntRinaldo Walcott

- 10.4COVID-19, Language, and IdentityAi Taniguchi

- 10.5Finding LanguageVanessa Dion Fletcher

- 10.6The Abundance and Conflict of On-Demand WritingLouise Hickman

- 10.7UnlanguagingJesse Chun

- 10.8An Infinity of TracesMatt Nish-Lapidus

- 10.9Speaking Out: Researchers on Pandemic-Era HealthcareZoë Dodd, LLana James, Laura Rosella

- 10.10Living ScoresOana Avasilichioaei

- 10.11Pronouncing (Un)FreedomShama Rangwala

- 10.12blertJordan Scott

- 10.13In Protest and Choir SongMaandeeq Mohamed

- 10.14In Support of the CensureJacob Wren

- 10.15Glossary

Finding Language

- Vanessa Dion Fletcher

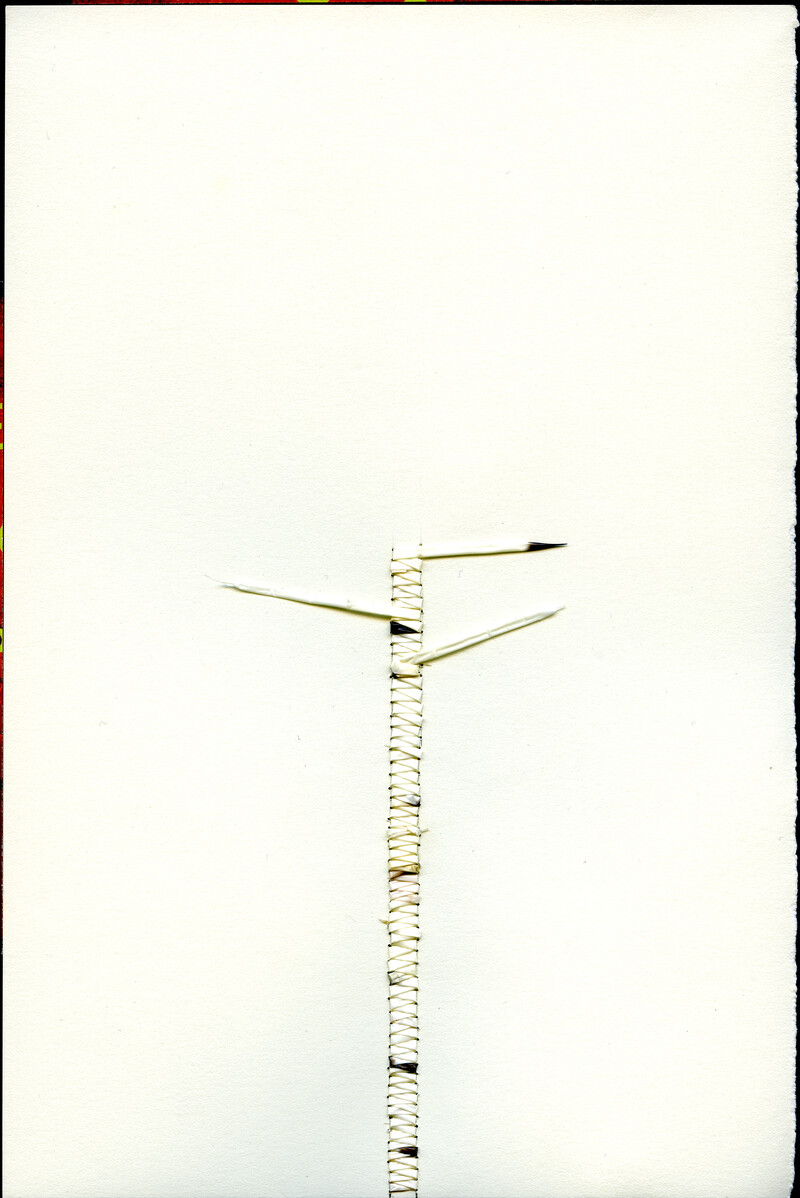

Zigzag in Twenty Nine Parts is from a series of embroidered porcupine quillworks on paper that Dion Fletcher conceives as a pathway for finding language. Intricately woven in alternating directions, the zigzagging design of cream-coloured quills is the result of a meticulous and laborious process, in which the Indigenous craft operates at the level of language. The composition leaves a compelling trace of Dion Fletcher’s work. Enigmatically inhabiting the page, the quillwork functions as a non-normative approach to language that brings the artist closer to her Lenape culture.

Finding Language

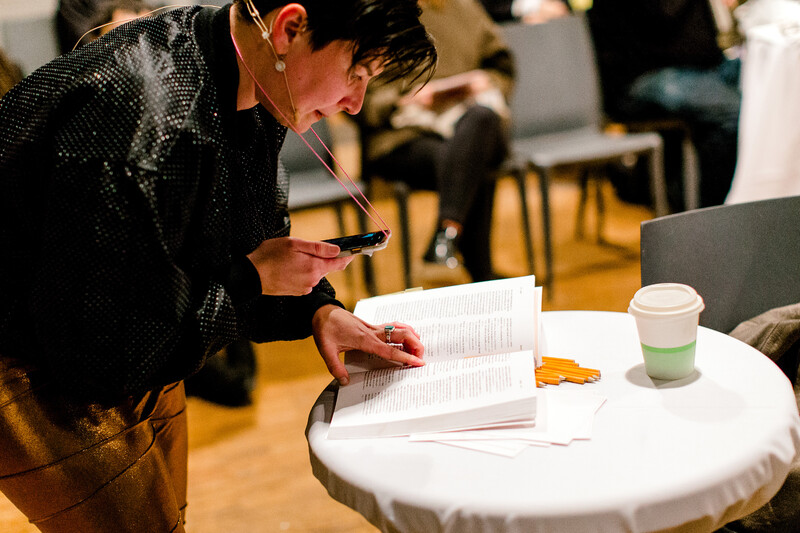

As part of a residency with Bodies In Translation (BIT), Vanessa Dion Fletcher developed the performance Finding Language: A Word Scavenger Hunt. This performance animates Dion Fletcher’s multi-layered relationship with spoken and written languages as a Potawatomi-Lenape artist who is seeking out her traditional and disappearing Lenape language (called “Delaware” by colonizers) and as someone who identifies as learning disabled. The performance begins with audio of her grandmother, which fills the room. The voice tells family stories and then describes the process of getting older, becoming disabled, becoming dependent. Overlaid in the audio, a child softly sings in what might be an Indigenous language—Lenape perhaps? As the audio ends, Dion Fletcher turns to focus on the Delaware-English/English-Delaware dictionary. As she begins to read aloud from this dictionary, it becomes clear that it offers distinctly colonial translations of the Lenape language.

With dictionary in hand, she sets out on a “word scavenger hunt” around the room. She roams the audience and the large room we are gathered in, in search of written words. As Dion Fletcher finds English words, which are plentiful, she translates them into the Lenape language using her dictionary. And the translations she finds are surprising, contentious, revealing. Take, for example, her discovery of a bag with multiple spellings of the English word “women”—“wimmin,” “womin,” “wimmyn.” Dion Fletcher slowly reads out these different spellings phonetically and then turns to her dictionary. As she thumbs her way through the English side of the dictionary in order to find the Delaware translation, she reads aloud other surrounding words: “White, white snow, be white, witch, hm.” Tension rises as the weight of colonialism fills the room. She finds the word “women” and reads aloud its related forms: “Indian woman, Delaware woman—that’s me!—white woman, schoolteacher, bad woman, good-for-nothing woman, woman with poor character [...] fat woman, be a bad woman, be a good-for-nothing woman, older single woman, hm.” Tension rises again.

Finding Language addresses the ways that Dion Fletcher has lost her language through the imposition of settler-colonialism and her struggles to orient to the language of settler-colonialism, a written language, because of the ways she delivers and receives language. In doing so, Dion Fletcher disrupts colonialism and presents new understandings of disability and its meaning in the world.

—Eliza Chandler

See Connections ⤴

As an Associate Professor in the School of Disability Studies at Toronto Metropolitan University, Eliza Chandler leads a research program that animates disability arts and its connections to disability rights and justice. This research interest came into focus when, from 2014-16, she was the Artistic Director of Tangled Art + Disability, an organization in Toronto dedicated to showcasing disability arts and advancing accessible curatorial practice. Chandler teaches in the areas of disability arts, critical access studies, social movements, and crip technoscience and participates in a number of research projects in these areas, including co-directing the SSHRC-funded partnership project, Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology, and Access to Life. Chandler regularly gives lectures on disability arts, accessible curatorial practices, and disability politics in Canada, and she is a member of the Royal Society of Canada’s College of New Scholars.

See Connections ⤴