- 11.0Cover

- 11.1How to Read this Broadsheet

- 11.2Power of PeopleAyodamola Tanimowo Okunseinde

- 11.3Walking through Mishibizhiw: Challenging the Measured Pace of ColonizationTasha Beeds

- 11.4Permanent PrecarityMostafa Henaway

- 11.5Soundpace // Eavesdropping on the Process of Dilettante ComposerOana Avasilichioaei

- 11.6Bringing the Decolonial into Kinesiology, Health, and Sport EthicsJanelle Joseph, Debra Kriger

- 11.7The Territory Between UsLee Su-Feh, Bracken Hanuse Corlett

- 11.8"Ensuring I Can Let People Know They Exist": Continuities of Black Feminist Publishing in TorontoAdwoa Afful, Cleopatria Peterson, Corinn Gerber

- 11.9Wayside SangCecily Nicholson

- 11.10Full StopMaandeeq Mohamed

- 11.11In Spite of DefeatismJacob Wren

- 11.12Glossary

Soundpace // Eavesdropping on the Process of Dilettante Composer

- Oana Avasilichioaei

It begins with desire. A longing for what is yet to be conceived. Faint and fragmentary glimmers of ideas, sound heard in the mind’s ear: elongated resonances, long drawn-out frequencies advancing and receding in waves, layers, reverberations // static, silent extensions // sometimes sparse, sometimes full // a sea of glass, a more active, rougher sea of surf and foam and wind // plucked chords // long vocal vowellings fading into breathlessness.

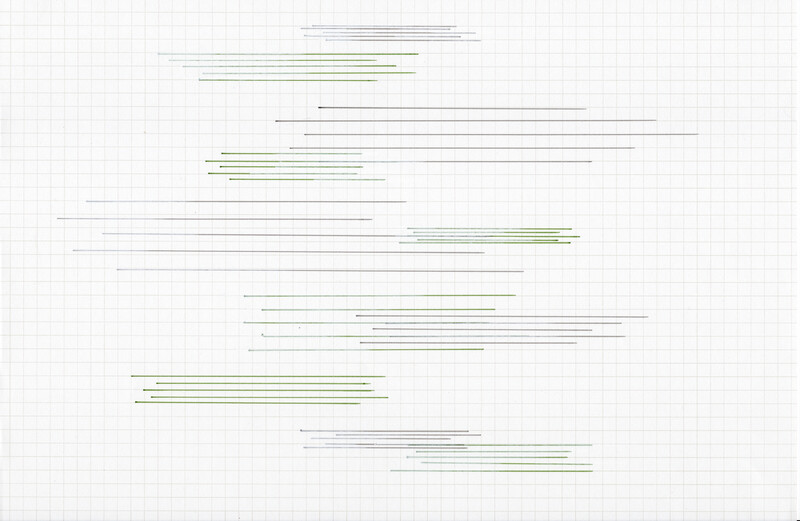

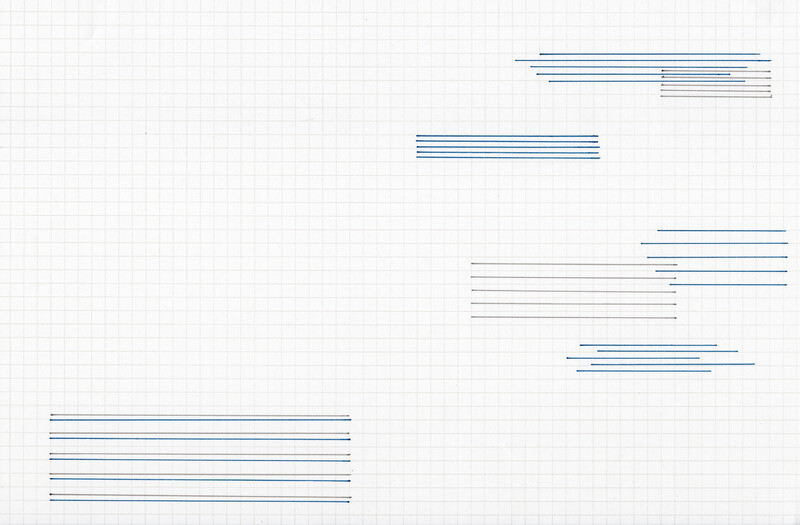

It began years before with the dilettante’s desire to learn something about sound and music (because unschooled) by drawing (with an instinctual, untrained hand) a series of graphic scores. Each a drawing in itself. A blueprint of potential. A visual musicality. Perhaps a future sounding. Or perhaps not. And even before that, it began with the excited feeling and compelling aural images inspired by the graphic scores of some of the greats such as Cornelius Cardew, Iannis Xenakis, John Cage.

The dilettante has read that pacing in compositional music has to do with selecting the tempo and overall rhythm for the performance of a score. Pacing in sound work, and certainly in the dilettante’s sonic essay, might then entail the apparent rate at which aural events take place, apparent because the sound, though transmitted rather than played, is still actively constructed in each moment by the types of speakers through which it is conveyed, by the space in which it is resonated, and by the listening ear-body (with all its particularities) and the location of that ear-body in the resonant space. Pacing thus shapes an aural elaboration in space and time, yet the contours of this elaboration remain, to some extent, porous or in flux. So one composes the simultaneous evolution and nowness of these aural events knowing that there will be variations in the impact of their pacing. So one composes with a certain (and arguably naive) sense of trust and a conviction of inevitable failure.

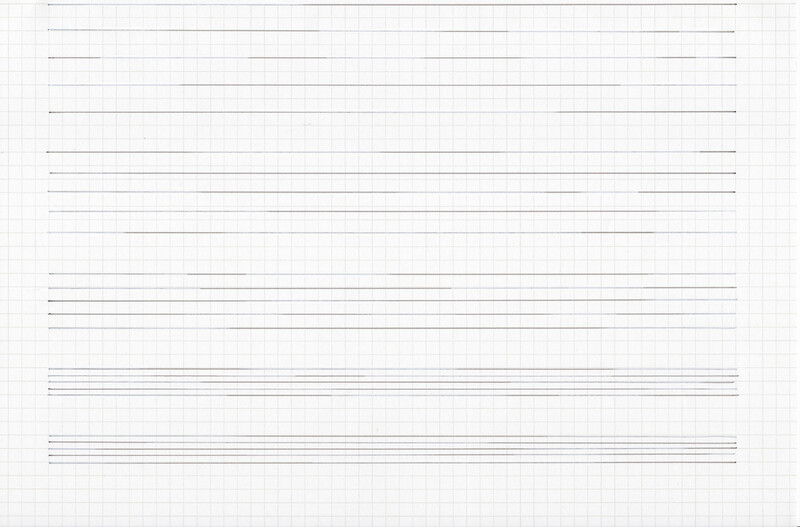

It began with the staff, the five horizontal lines that structure the composition of notes (in Western musical notation). It began with the lines because of the dilettante’s aspiration to draw sound though unable to read music. Thus the five lines of the staff would be made into markers of sound.

Much later, after enough drawings had accumulated, after a selection had been made, after a potential order or movement had been established, it began with translation. From the visual two-dimensionality of the page to a volumetric spatialization of sound across eight speakers (the dilettante still called them “speakers” then, though a more accurate word would have been “monitors”). The arrangement, spacing, length, thickness, shape, proximity, colour, and texture of the lines would combine to suggest various gestures, qualities, volumes, tones, and frequencies of sound.

Thus far, the dilettante had only ever worked in stereo. Although she was a long way off from exhausting its possibilities, over the years she had grown somewhat comfortable with its qualities; its potential for structuring audio had become familiar. The leap from stereo to octophonic was oceanic. Everything she had learned (often by scrambling in the dark) had to be unlearned and then learned anew. How sound would behave within and beyond the eight-source circle. How certain shorter, more staccato sounds would remain localized to one spot, moving out of it ever so slowly, while more melodic, elongated resonances would quickly fill the room.

Pacing here was suddenly so much more complex than anything the dilettante had ever considered before, for it was multidimensional, multifractal, a constant choice between a stationary point and a movement, between a solo, duet, trio, chorus, or a combination of all, between a focus and a dissipation, between a fullness and a fast wave, a fading and a rhythmic beat, between a circular progress and a linear expansion, all choices simultaneous, all choices exponentially increased by a factor of eight.

At first, the dilettante tried to assign an “instrument” to every aspect of the lines, a time frame to every drawing. However, this quickly failed and it became evident that she must build the piece holistically. For every segment, as one stood in the middle of the room of speakers, she wanted one to feel as though they were standing in the middle of the drawing. In certain segments, some of the qualities of the lines would be more present while others would be more muted. The time and pacing of the segments would vary. Sonic lines, linear soundings, fading reverbs, growing distortions, washes of sound.

The dilettante selected, reselected, selected again, and chanced upon her instruments: the wet sound of a processed theremin, the raw melodies of a prepared piano somewhat out of tune, the noisy textures of various objects and drawing implements captured with contact mics, the distortions of an old zither, an improvised gong, the vocal spectre of the breath. A sense of a trace, of bareness, a shadow or suggestion of something more concrete yet that remained just out of reach was at the core of her selection.

There is a skill (which the dilettante could barely graze with her fingertips) to knowing when to let loose and when to hold back, when to add and when to remove, when and how to sculpt silence, when to build on or continue or devolve or work against what came before, when and how to be aleatory, when to defy expectations created by a particular moment and surprise or when to deliver on those expectations, when and how to make peaks into transitions and transitions into endings.

It began each day with a listening session of the whole, with note taking (such as: use theremin with reverb but no volume on theremin so record only the wet // use fainter paperdraw 33 for lighter yellow parts of the lines // record textures: cat brush, pine cones, chopsticks, plastic fork on paper // create longer transitions // maybe extend zoom 28 so fade-in is longer // maybe warp texture 18 further // bring back a sound, altered or unaltered), with ideas for changes, for the next, with listening to potential sound already recorded, or with recording more. It developed slowly, drawing by drawing, second by second, in multiples of channel combinations. There was a semblance of form and of building, but also of disintegration, suspension, a tense promise of what is to come, a memory of what has not yet happened.

About halfway through the process, the dilettante asked for some feedback, a few trusted reactions on the work thus far: a sense of being out of time, out of space, prehistoric // spectral presences, eerie, lurking soundings but largely falling between as most of the sounds can’t be placed // begins in a more intimate, contained space, then moves outward, later returns to another, more intimate space embodied through a rotating, almost centripetal breath, then moves outward again, ever more outward // a sense of structures and shapes // sometimes very abstract, material, textural, other times more suggestive of images, atmospheres, figures, almost painterly // an organic machine // cinematic // electronic with much organic physicality // the dissolution of radio static.

Then the process went on, the work evolved, morphing ever so slightly with each change, addition, deletion, failed direction, progression, moment of attention. Though a semblance of an ending was eventually reached, the aural labour continues. It begins again and again and again. There is much refinement to be done, the intricacies of the pacing, the activation of the volumes, and the embodied reactions of the ear-bodies to be reconsidered. The octophonic work might only ever be completed in a moment of listening, once it has entered and reverberated off an individual ear-body in a particular space. And then in another. And then in another. And even then, will it ever truly be finished?

See Connections ⤴