- 11.0Cover

- 11.1How to Read this Broadsheet

- 11.2Power of PeopleAyodamola Tanimowo Okunseinde

- 11.3Walking through Mishibizhiw: Challenging the Measured Pace of ColonizationTasha Beeds

- 11.4Permanent PrecarityMostafa Henaway

- 11.5Soundpace // Eavesdropping on the Process of Dilettante ComposerOana Avasilichioaei

- 11.6Bringing the Decolonial into Kinesiology, Health, and Sport EthicsJanelle Joseph, Debra Kriger

- 11.7The Territory Between UsLee Su-Feh, Bracken Hanuse Corlett

- 11.8"Ensuring I Can Let People Know They Exist": Continuities of Black Feminist Publishing in TorontoAdwoa Afful, Cleopatria Peterson, Corinn Gerber

- 11.9Wayside SangCecily Nicholson

- 11.10Full StopMaandeeq Mohamed

- 11.11In Spite of DefeatismJacob Wren

- 11.12Glossary

Full Stop

- Maandeeq Mohamed

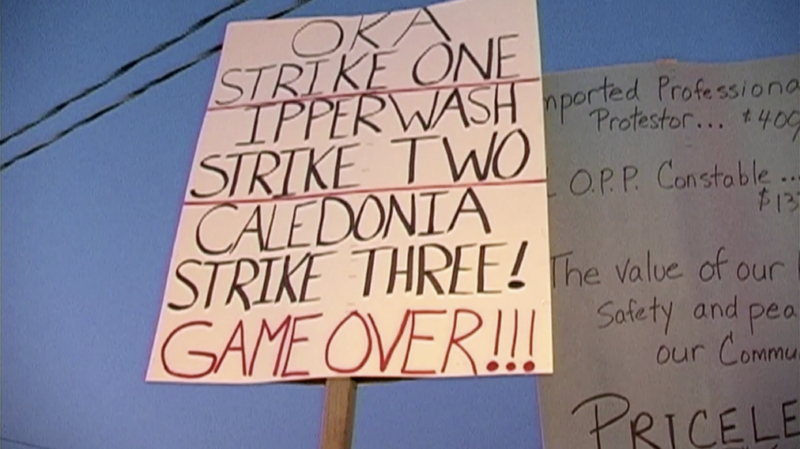

How to frustrate the time of empire, when settler colonialism presents itself as inevitable, encompassing past, present, and future, as if nothing exists outside it?11Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. In “Suspending Damage,” Indigenous studies scholar Eve Tuck writes of another time, of a desire that evinces decolonial temporalities at the juncture of “the not yet and, at times, the not anymore.”22Quoted in Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (Fall 2009): 417. The not anymore holds the promise of inevitable decolonization (after the dictum of so much movement building: “all empires fall”). And the not yet suggests that this end will come sooner than we might think. I want to read scenes of the blockade as countering the pace of settler colonialism, toward this not yet and not anymore. Consider the protest site 1492 Land Back Lane,33Support 1492 Land Back Lane’s legal fund at https://www.gofundme.com/f/legal-fund-1492-land-back-lane.located in what is sometimes called Caledonia, Ontario, where land defenders are protecting their lands from colonial-capitalist development. On July 19, 2020, Six Nations land defenders occupied the McKenzie Meadows development site, where Foxgate Developments planned to construct 218 houses on Haldimand Tract lands, and renamed it 1492 Land Back Lane. On August 5, 2020, the defenders were arrested, prompting the community of Six Nations to block several roads, Highway 6, and the CN rail line, disrupting commerce.44J. P. Antonacci, “A Guide to Understanding the Land Issues in Caledonia,” Hamilton Spectator, October 29, 2020, https://www.thespec.com/news/hamilton-region/2020/10/29/a-guide-to-understanding-the-land-issues-in-caledonia.html.In interrupting the railway’s flow of commodities and people, the pace of settler time is slowed to a pause at 1492 Land Back Lane.

Almost a year later, Foxgate Developments announced the cancellation of the development at 1492 Land Back Lane, citing the land defenders’ occupation as having “no sign of ending.” Foxgate’s description of Haudenosaunee resistance as “unending” echoes state-led reconciliation efforts oriented toward “moving forward” to avoid the kind of anticolonial organizing that would challenge the existence of the Canadian state and the profits of private property. In 2008, for instance, Indigenous studies scholar Glen Coulthard identified the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as directly linked to the Canadian state’s anxieties over 1990s Indigenous resistance movements, such as the Kanehsatà:ke resistance.55Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill and Sophie McCall, The Land We Are: Artists & Writers Unsettle the Politics of Reconciliation (Winnipeg: ARP Books, 2015), 7–8.Almost a decade and a half later, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service gave an internal report on the “disruptive implications” of 1492 Land Back Lane in these terms: “Critical infrastructure near the camp has been damaged, vandalized or disrupted during the protest. The damage to critical infrastructure and the potential disruption to services have implications not only for Caledonia, but southern Ontario as a whole.”66Brett Forester, “Top spy agency tracked Caledonia land dispute as possible threat to national security: secret document,” APTN News, June 29, 2021, https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/spy-agency-tracked-caledonia-land-dispute-as-possible-threat-to-national-security-secret-document/.If the state needs to “reconcile” and “move forward” to avoid further anticolonial organizing that would challenge both the existence of the Canadian state and the profits of private property, then Haudenosaunee sovereignties showing “no sign of ending” insists on an altogether different pace. At 1492 Land Back Lane, the pace of settler colonialism is brought to a disruptive halt when a desire for the time of not yet and not anymore exists outside reconciliatory state gestures. A billboard on the former McKenzie Meadows development reads: “Your kind of community.”77Antonacci, “A Guide to Understanding the Land Issues in Caledonia.”Is the “your” in Foxgate’s advertisement the same “your” as in Ontario’s slogan of “Yours to discover?” Named after the year Christopher Columbus claimed he discovered the Americas, 1492 Land Back Lane—five hundred years later—refuses the language of colonial discovery and possession that defines Ontario’s tourism sector; instead, it insists on the sovereignty of unceded Haudenosaunee territory: this is 1492 Land Back Lane.

I want to think through the kind of stoppage that 1492 Land Back Lane evinces alongside the work being done by the innumerable tenant unions and organizations across Toronto. Groups like the Goodwood Tenants Union and People’s Defence, who have successfully blocked the eviction of numerous tenants during the COVID-19 pandemic, refuse the settler logic of defending private property on stolen land. On September 21, 2020, members of the Goodwood Tenants Union (a collective of tenants at 108 Goodwood Park Court, East York) protected one of the building’s residents from eviction.88See Joanna Lavoie, “Tenants, Supporters Block Sheriff from Enforcing Eviction Order in East York,” Toronto.com, September 21, 2020, https://www.toronto.com/news-story/10205681-tenants-supporters-block-sheriff-from-enforcing-eviction-order-in-east-york/.When the sheriff and several police officers arrived to enforce the eviction order, dozens of Goodwood tenants prevented their entry into the building. And on April 17, 2021, when twenty-six police cruisers arrived at 33 Gabian Way, York, to evict a father and his two children, the presence of dozens of members of People’s Defence (a Toronto-based eviction defence group) placed enough pressure on the landlord to halt the eviction and negotiate a new lease with the tenant.99Miriam Katawazi, “Single Father of Two Says Toronto Police Stormed His Building as he Faced Eviction amid COVID-19 Pandemic,” CTV News, April 7, 2021, https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/single-father-of-two-says-toronto-police-stormed-his-building-as-he-faced-eviction-amid-covid-19-pandemic-1.5377734.If the police as an institution exists to protect private property (consider the more than $16 million spent by the Ontario Provincial Police in half a year to police 1492 Land Back Lane as just one example of how the colonial history of policing in the Americas continues today), then communities of tenants protecting their neighbours present a kind of blockade on stolen land.

Over the past year, alongside this work being done by tenant unions, labour unions have produced similar stoppages of their own. On April 26, 2021, thirty-five United Steelworker members at a Rexplas bottle-packaging plant walked out to demand better pay from their employer. Despite a 21% increase in revenue from pandemic profits, Rexplas did not increase employee wages until weeks of striking had taken place.1010Business Wire, “Pandemic Profiteers Must Pay Workers Fairly: United Steelworkers,” Financial Post, June 2, 2021, https://financialpost.com/pmn/press-releases-pmn/business-wire-news-releases-pmn/pandemic-profiteers-must-pay-workers-fairly-united-steelworkers.Throughout 2020–21, staff at various Toronto District School Board schools have refused work due to concerns about the spread of COVID-19.1111Joshua Freeman, “Support Staff Concerned about COVID-19 Begin Work Refusal Process at Toronto Special Needs School,” CTV News, January 25, 2021, https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/support-staff-concerned-about-covid-19-begin-work-refusal-process-at-toronto-special-needs-school-1.5281758; Chris Herhalt, “Staff Who Refused Work at Elementary School Dealing with COVID-19 Outbreak Will Make Their Own Decisions on When to Return: Union,” CP24, November, 2, 2020, https://www.cp24.com/news/staff-who-refused-work-at-elementary-school-dealing-with-covid-19-outbreak-will-make-their-own-decisions-on-when-to-return-union-1.5170661.And, in the summer of 2021, frontline healthcare workers at Black Creek Community Health Centre, deemed essential throughout the ongoing pandemic, went on strike to demand a provincially mandated 1% wage increase.1212Ontario Public Service Employees Union, “Media Advisory: Black Creek Community Health Centre Workers Take Strike to Minister of Health,” Cision Canada, July 13, 2021, https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/media-advisory-black-creek-community-health-centre-workers-take-strike-to-minister-of-health-807086846.html.Amid these labour stoppages as workers demand fair pay and safer working conditions, labour shortages have been further impacting various industries across Ontario, from restaurants to automotive manufacturing.1313Nicole Williams, “Recruiting ‘a Nightmare’ for Restaurants as Ontario Loosens Indoor Dining Restrictions,” CBC News, July 13, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/covid-19-labour-shortage-1.6099624; Mark Rendell, “Canadian Companies Deal with Supply-Chain Bottlenecks amid Recovery,” Globe and Mail, May 31, 2021, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-canadian-companies-deal-with-supply-chain-bottlenecks-amid-recovery/.According to a May 2021 report by CIBC, “Canadian businesses could still run into issues as they attempt to reopen or expand their workforces. Under the CRB [Canada Recovery Benefit], people have an incentive to return to work, but that incentive diminishes the more they earn [from the benefit].”1414Benjamin Tal and Andrew Grantham, “Where have all the workers gone? Surging job vacancy rates post-pandemic,” CIBC Economics in Focus, May 26, 2021.In CIBC’s calculation, workers’ precarious experience of making more money from COVID-19-related unemployment benefits than they can in below-living-wage jobs is reduced to a labour “issue.” Is “labour shortage,” here, rather a euphemism for workers refusing to return to their exploitation? A euphemism for the farms across Ontario that are COVID-19 hotspots, causing outbreaks among migrant farm workers?1515See, for example, "Workers Speak Out for International Migrants Day: Open Letter,” Harvesting Freedom, December 18, 2020, https://harvestingfreedom.org/2020/12/18/workers-speak-out-for-international-migrants-day-open-letter/.The language of reports like CIBC’s often invokes the idea of a block: employers “run into issues,” “shortages,” or “challenges” that disrupt the pace of “economic recovery” (for who?).1616Williams, “Recruiting ‘a Nightmare’ for Restaurants.”Such stoppages evoke similar scenes as the ones enacted by the eviction blockades of tenant unions across Toronto and by the land defenders refusing colonial development on unceded Haudenosaunee land. These sorts of blockades introduce a pause, refusing the terms of exploited labour and private property on stolen land. And this pause is expansive, encompassing the not anymore demanded by striking workers and by tenants who prevent the eviction of their neighbours on stolen land. Sitting in this pause can offer a window to a not-yet-here but soon-to-come end to empire.

See Connections ⤴