- 01.0Cover

- 01.1Geologic Time SpiralLisa Hall

- 01.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 01.3How to Graft a CityShannon Mattern

- 01.4IntersectionsMorris Lum

- 01.5Climate Change: An Unprecedentedly Old CatastropheKyle Powys Whyte

- 01.6The LEAP ManifestoLEAP

- 01.7Decolonizing the AnthropoceneHeather Davis, Zoe Todd

- 01.8This, Seeded in a GlanceJulie Joosten

- 01.9Tree Permit TP-2016-00332Kika Thorne

- 01.10Prosthetic CarapaceAmanda Boetzkes

- 01.11Pollution is ColonialismEndocrine Disruptors Action Group, Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research

- 01.12What is The Economy?D.T. Cochrane

- 01.13Serpentine GalleriesFraser McCallum

- 01.14Credit Valley Conservation Authority: Nature/Culture/NatureAndrea Olive

- 01.15Learning from Natural Assets

The Climate Change Project, City of Mississauga

- 01.16Local Useful Knowledge: Resources, Research, Initiatives

- 01.17Glossary

Prosthetic Carapace

- Amanda Boetzkes

Grafting has emerged as an insistent figural operation at a time when sensory environments are charged with colliding political and ecological forces. Indeed, we can think of such conflicts as incisions into the defense structure of the subject from which new material trajectories grow. New carapaces are being constituted at the site of ecological wounds. The graft is therefore ambivalent—neither a suture nor a bandage, but a layer that integrates itself to form a resilient but receptive shell for a new condition. Artistic grafting implants offshoots that propagate outward growth in unforeseen directions. But it also involves ingrowth, the corporeal acceptance of foreign material. Grafting is thus an aesthetic activity that spans epistemological and ontological concerns.

Consider Pierre Huyghe’s Untilled installation at Documenta 13 in 2012. Like much of Huyghe’s work, Untilled staged discrete animal and vegetal Umwelten—lifeworlds—that overlapped but nevertheless maintained gaps of indifference toward one another. The outdoor installation was composed of a sculptured nude set amidst groupings of poisonous nightshade plants, fungi that produce LSD, and toxic flowering foxgloves. A greyhound named Human with a dyed pink leg lived on the plot of land, moving freely about the site with no constraints. These disparate components—or as Huyghe describes them, these “alive entities and inanimate things, made and not made, dimensions and duration variable”—were gathered together by a focalizing agent, a graft at the core of the sprawling dimensions: a colony of bees built a massive hive around the head of the sculpture, thus seaming together the numerous divides in the space. In grafting concrete and honeycomb, it joined sites of meaning and meaninglessness; the signifying world of art and the signaletic world of bees. The graft flattened the expressivity of the work to articulate a paradox: the capacity to communicate across ontological difference is shown as the sculpture’s incommunicability. The face of the female figure was remapped as the bees’ dominion.

Grafting crosses realities and binds them together by asserting the very material excess of its procedure. It injects exterior matter into interior content and projects interior content outwards. In this way, a graft behaves like a frame or pedestal to the work of art, or what Jacques Derrida calls the parergon: a device that indicates the space of art and without which art would not be what it is. In The Truth in Painting, Derrida argues that framing and ornamentation are integral components of the meaning of the artwork. The ergon (the work of art) is offset by its parergon, the limit that separates the work from what lies outside it, thus binding the two together. Derrida shows how Kant established a model of aesthetics based on an elaborate conception of the artwork, using framing devices as prostheses that are necessarily integral to the work’s internal subject matter. It is therefore only by virtue of the external parerga, the scaffoldings that deliver the work of art as art, that Kant can make aesthetic judgments based on internal criteria. In other words, the world of art is upheld by frames.

The parergon is not a literal frame, but rather a procedure of encircling, supporting, and presenting the work of art. Derrida maintains that the relationship between the artwork and its parergon may be as close as that between the drapery and inferred body of a classical sculpture. The drapery is material excess, a supplement without which there would be no sense of the body. Yet the drapery is not an interior or intrinsic component of the complete representation; it belongs to the work in an extrinsic fashion.11Jacques Derrida, “The Parergon,” trans. Craig Owens, October 9 (Summer 1989): 21. It adorns and veils the nudity of the body. But precisely as a supplement on the edge of the work, it naturalizes the representation itself.

Grafting similarly undertakes this activity of supplementation. As in the case of a skin graft, a material supplement is applied in order to (re)constitute the whole organ. The graft must be absorbed into a seamless totality in order for the skin to function as the body’s primary organic boundary. In grafting, we see the fundamental excess of all concepts and terms: the graft points to ruptures and affordances. Like Derrida’s frame, it forms and deforms, and we might also consider how grafting in-forms. The excess of the graft feeds back into the work and even has the potential to recast intention and meaning. Grafting applies a surface that is both sensorial and informational, a bi-directional interface that grows excessively in the fissures of meaning and orientation. Through its interweaving of that excess, it produces new skeins of sense.

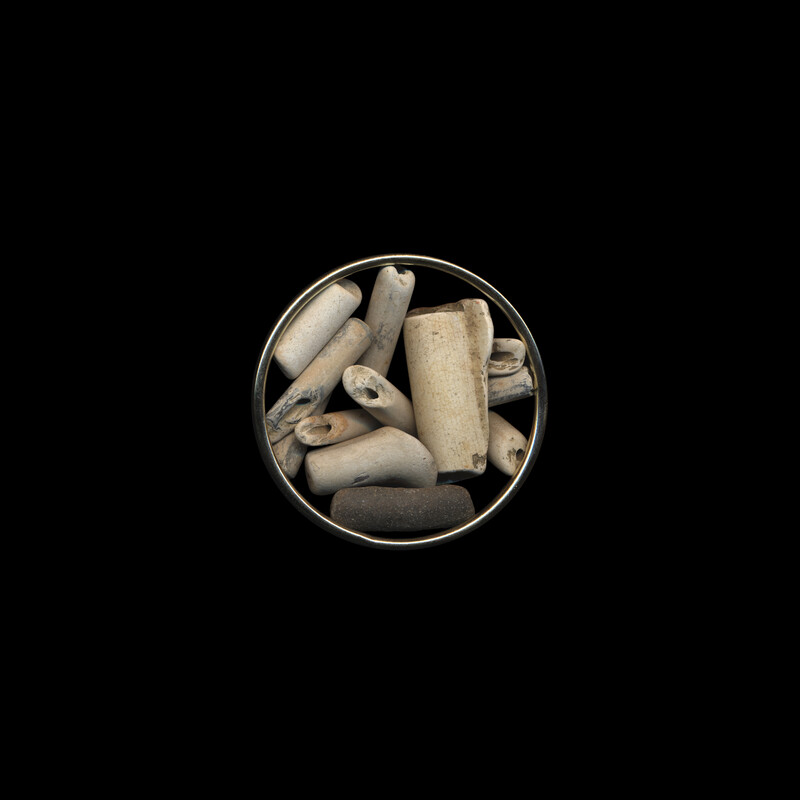

Consider Nadia Myre’s work Code-Switching (2017), comprised of photographic images of clay-pipe fragments woven with Indigenous beadwork. Set against a black background, the objects call to mind traditional ceremonial dress. Yet the work switches the visual code of the object, implanting it with inferences of its colonial history. A Montreal-based artist and member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, Myre began the work as a study of the tobacco trade. She and her son recovered the pipe-fragments from the Thames River, debris from a time when traders would dock in London with ships full of imported tobacco from the “New World,” where goods and resources were circulated on trade routes that spanned the Atlantic. Myre’s recovery of the clay pipe becomes an act of grafting: she sews the pieces into a fabric that supplements traditional beadwork with the material remains of the tobacco trade. The fragments bind together the total object but nonetheless inform it with a new code: a colonial history and decolonizing intervention. She inflects the visual code of all beadwork, insisting on its historical and material specificity in lieu of timeless mythologies of Indigenous craft. In so doing, her graft-work resists the historical masking of colonial violence and deterritorialization.

But grafting does not merely inflect; it transforms through the movement of informational relay, making incisions into visual contextures and recoding them. The effects of such manoeuvres are more than instructive, however, as recoding changes both perspective and experience. It brings materiality to the horizon’s edge and resonates with what lies beyond the world. The graft therefore resounds between the virtual and the material, generating sensible possibilities at the limits of discursive knowledge. When Australian artist Stelarc grew a full-sized ear from his own tissue and surgically inserted it into his arm, he did so to resituate the body’s sensorial orientations and to intervene in the way that others direct their input. Ear on Arm is one of several prosthesis projects designed by Stelarc to “augment the body’s architecture, engineering extended operational systems of bodies and bits of bodies, spatially separated but electronically connected.”22Stelarc, Ear on Arm: Engineering Internet Organ, http://stelarc.org/?catID=20242. His work does not intend to reconstitute a body that is missing an existing organ or limb, but rather to explore the possibilities of extending, repurposing, and reconnecting the body to the external world. Importantly, the ear is rigged with a wireless internet connection and a microphone, so that it will serve as a communicative organ that both receives and outputs information. Stelarc envisions that it could also be a remote sensor, so that someone across the globe could tune into it and listen to what it hears. Furthermore, it would be part of a distributed remote communication system, in which a speaker would be implanted in Stelarc’s mouth so that he might talk to someone by speaking into the ear on his arm, and hear the answer from the implant in his head. Stelarc has thus grafted a new sense system into his body in such a way as to problematize corporeal boundaries altogether. His prostheses collapse the naturalized parameters of the body, closing the spatio-temporal gaps that separate individuals by building an exoskeleton by which others are assimilated into its fabric.

Grafting is therefore ambivalent. It anticipates, speculates, and feeds back, but the procedure is not always successful, confronting material recalcitrance and historical reflexes. Grafting takes place against the repetitions of “nature,” colonial oppression, the capitalist psyche, and bodily repression. It is anticipatory yet must also protect against grooved patterns of reification; it attempts to reset the nervous energies bound up in our perceptual reactivity. Grafting is a “perlocutionary gesture,” as Judith Butler defines it—a performative act constituted by the very possibility of failure, by virtue of the existing discourse into which it is performed.33Judith Butler, “Performative Agency,” Journal of Cultural Economy 3, no. 2 (2010): 152. It runs up against the existing contexture in all its extended material implications. It is not surprising to note that Stelarc’s implants have suffered from necrosis and have had to be removed and re-implanted. Grafts can indeed be rejected and feed their failure back into the host system. Grafting is therefore a risky practice and not merely an exercise of the imagination.

The feedback of the graft, whether utopian extension or dystopian infection (or both at the same time), intercedes in the processes of anthropogenesis by generating communication with the assemblage of forces that make up the earth’s ecology. In this regard, let us consider Mary Mattingly’s Wearable Homes series, which imagines portable architecture as superadded layers to the body, designed to respond to global climate change. Through these fabricated carapaces, she grafts bodily reflexes and sensibilities. In turn, climate is incorporated into individual movement, habitation, and response capabilities.

The Wearable Homes designs take clothing patterns from a variety of cultural traditions, information technologies, and portable energy systems. Through these components, the architecture of each Wearable Home is designed for a subject that will be exposed to volatile climates without an anchored geographic location. In fact, it anticipates the very undoing of cultural identities grounded in environmental consistency. Mattingly’s templates derive from Inuit garments, Indian saris, Buddhist robes, American chains like The Gap and Banana Republic, Japanese kimonos, safari camouflage, and military uniforms. The synthesized textiles protect the body and provide it with a general global form.

Mattingly relates the general globality of the Wearable Home to an understanding of the clothing’s sheltering capacity, insofar as she notes that one wearer would be indistinguishable from the other. At the same time that this would provide for privacy and anonymity, however, she notes that “the pervasiveness and scrutiny of high-powered networks would still catalog our movements and whereabouts.”44Mary Mattingly, Wearable Homes, http://www.marymattingly.com/html/MATTINGLYWearableHomes.html. The home would be outfitted with an information technology mainframe, so the wearer could receive and transmit signals via GPS, cell phone networks, VA goggles, and the internet. Additionally, the home would be outfitted to inflate in water, with solar panels to provide electricity, warming and cooling fabrics, and batteries recharged through bodily motion by power sensor nodes. Each home would also have thirty pockets to fit the pills necessary for a month of “mood and health monitoring.” In short, the affordance of this intelligent membrane is precisely its plasticity: its endurance through any and all climates—political, environmental, cultural, and subjective.

Wearable Homes is a speculative fiction of the entanglement of the body, climate, and aesthetics, which Mattingly sets in moody dystopian landscapes in her photographic series. The Wearable Homes appear in the charged environments for which they were designed. Lone individuals appear against dark, cloudy skies, craggy cliffs, or churning waters. The images thus enact grafting as a response to the systemic interplay between body and climate, with all the political and technological entanglements this implies. It gives articulation to the form and movement of grafting, creating mediatized sense-objects that are at once interfaces with possible worlds and hypothetical objects of those worlds. As grafting envelops and moves between interiorized and exteriorized realities, inverting and extroverting, it weaves a syntagmatic chain that runs through the speculative real and feeds back a retrospective sensibility. Its operation serves as what Félix Guattari calls a chaoide, an intervention to unlock the body from its nervous repetitions and open material possibilities.55Félix Guattari, Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995).

See Connections ⤴