- 06.0Cover

- 06.1Whose Woods These AreZackery Hobler

- 06.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 06.3An Open Letter to Extinction RebellionWretched of the Earth

- 06.4Forging the Land on PaperBonnie Devine

- 06.5Rag CosmologyErin Robinsong

- 06.6Golden FuturesOrit Halpern

- 06.7for the watersAlize Zorlutuna

- 06.8The Collective Afterlife of ThingsSarah Pereux, John Paul Ricco

- 06.9Closing the Carbon Loop with Artificial PhotosynthesisPhil De Luna

- 06.10A Dictionary for the Future PresentThe Bureau of Linguistical Reality

- 06.11ExtractionsThirza Cuthand

- 06.12To Be RepairedJoy Xiang

- 06.13Demon Copper

Michael DiRisio

- 06.14What is Value?D.T. Cochrane

- 06.15The Blue Dot MovementCiara Weber

- 06.16Local Useful Knowledge: Resources, Research, Initiatives

- 06.17Glossary

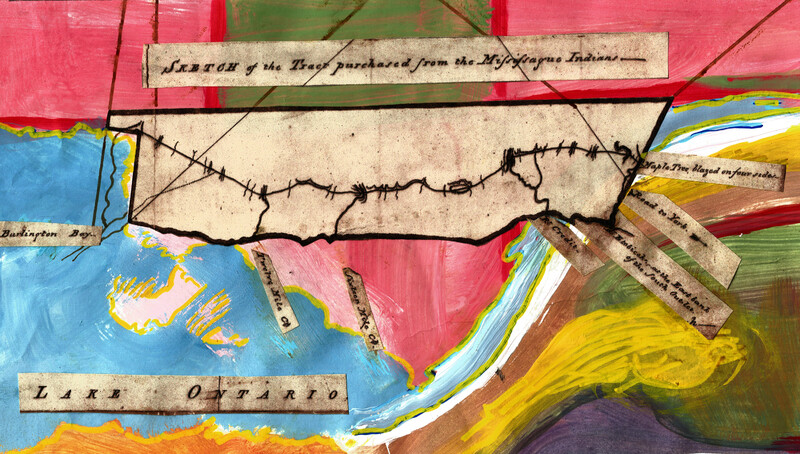

Forging the Land on Paper

- Bonnie Devine

There is a way to come to land that disavows the body. The tools of hearing, touch, and smell are not necessarily deployed, nor are feet or hands required in this exploration of country. It is an abstract process and almost entirely imaginary, except for the schematic representations that support and record the gradual disintegration of being and place into an official image and a bureaucratically administered fiction.

The maps in the University of Toronto archive provide the substrate for an exploration without travel, a long trek in the mind, and yield something like knowledge but in the end something not at all like knowledge of the river and the paddle and the lake.

On paper water stretches flat, shallower than the thinnest hide; earth wraps over ridges and under ravines like a drapery of carbon one micron deep. The eye slides over. The mind races past. Congestions of letters give up the names. Here lived the Mississaque. Here mouthed the green river against the breast of the great lake.

Tracts illustrating potential military approaches by competing colonial armies or resistant Indigenous forces are given special attention. Soberly invented campaigns unfold from their surfaces, dispatches to troops tensed along the borders are sent out to the frontier. Here there be dragons. Here a clear unimpeded thoroughfare.

The marches are measured and calculated. Lines drawn in crayon or sometimes careful inks sketch out the fate of the marshland and the distant combatants. The chart’s overworked surface obscures the shouts from the field.

In the event, bloodshed was unnecessary. The act of boldly marking up the page was sufficient to simultaneously claim and secure the territory.

We do not know all the approaches to this place, though the map confidently insinuates the opposite. As if the canoe paddle had dipped into the liquid ink, as if the morning sun had glinted off its arcing steel nib.

A hundred years later we still do not know beyond the sounder’s figurations what lies beneath.

But the genius of numbers and measurement ensures domestication, and the insult of an island’s lithe autonomy is overthrown in the rendering. An artist in downtown Toronto imagines ships and traces the outline of Pier Seventeen. A harbour is born.

A thousand years from now will we understand better the mysterious vestige of the island in its vessel of sweet green water? Will we account for its margins and depths more honestly?

Stretches of forest become landscape. A tracery of connecting lines, mostly straight, are ruled on the surface. A grid presses lightly against the mountain’s face and zigzags across the pastures of grasslands and shield lands right up to the pole. The pole. Yes. Even this is drawn as the imagined structure securing us in unabating movement.

Like the flower, the lakes and the land are thus taken and named.

The forger’s work concluded, the papers bearing these marks lie forsaken yet hoarded in a drawer at the university, the remains of the settlers’ lust for dominion. Their rectification is our future work.

All artworks courtesy the artist, 2019. Maps sourced digitally without restriction at the University of Toronto Map and Data Library

A member of Serpent River First Nation, Genaabaajing, an Anishinaabe Ojibwa territory on the north shore of Lake Huron, Bonnie Devine's work emerges from the storytelling and image-making traditions she witnessed as a child. Her art explores issues of land and environment, treaty and history. She is an artist, curator, writer, and educator. Though formally educated at the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD U) and York University, her most enduring learning came from her grandparents, who were trappers on the Canadian Shield. Devine’s installation, video, and curatorial projects have been shown in solo and group exhibitions and film festivals across Canada and in the USA, South America, Russia, Europe, and China, including the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Berlin Film Festival, the National Museum of the American Indian, and Today Art Museum in Beijing.

See Connections ⤴