- 09.0Cover

- 09.1Because You Know Ultimately We Will Band A MilitiaXaviera Simmons

- 09.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 09.3Four Movements of DiffusionSophia Jaworski, Zoë Wool

- 09.4Water Filtration System: Floating University BerlinKatherine Ball

- 09.5Looking for a CureIrmgard Emmelhainz

- 09.6Theory of IceLeanne Betasamosake Simpson

- 09.7Legible Motivations: "Not Everything is Genuine"Nehal El-Hadi, Mark V. Campbell, Elicser Elliott, Charles Officer

- 09.8As if our Future Past Bore a Bad AlgorithmLiz Howard

- 09.9The Neurocultures Collective: Co-creating Moving Images

- 09.10ReceiptsImmony Mèn, Lilian Leung

- 09.11Weaving a Local, Grassroots WebJoy Xiang

- 09.12The First ChapterJacob Wren

- 09.13Glossary

Water Filtration System: Floating University Berlin

- Katherine Ball

How will life change as our relationship to water transforms and we shift from being consumers of water to stewards of water?

Floating University Berlin is a nature-culture learning site. It is located in a polluted rainwater collection basin connected to Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin. During Floating University’s inaugural year, artist Katherine Ball helped design, build, and maintain a water filtration system that uses biological filters to clean polluted water on site.

Floating University was erected on a concrete basin built to gather rainwater runoff from Tempelhof Airport (the Nazis’ prized airport during World War II), and this location provides layers of history that contribute to the symbolism of experimental water usage and conservation. Floating University began in 2018 as an experimental offshore university for cities in transformation convened by the architecture group Raumlabor. It brings together neighbourhood residents and students from universities across Europe and the world to conduct interdisciplinary educational experiments reimagining how we can live together in contemporary urban space. In its inaugural year of 2018, over 10,000 people visited and participated. A successful citizens’ referendum against the construction of high-price housing in Tempelhof has frozen all development there, and so the mid-century infrastructure of the rainwater basin must remain in place until the development debate has been resolved. Today, Floating University is stewarded by an association of 40 members, called Floating e.V.

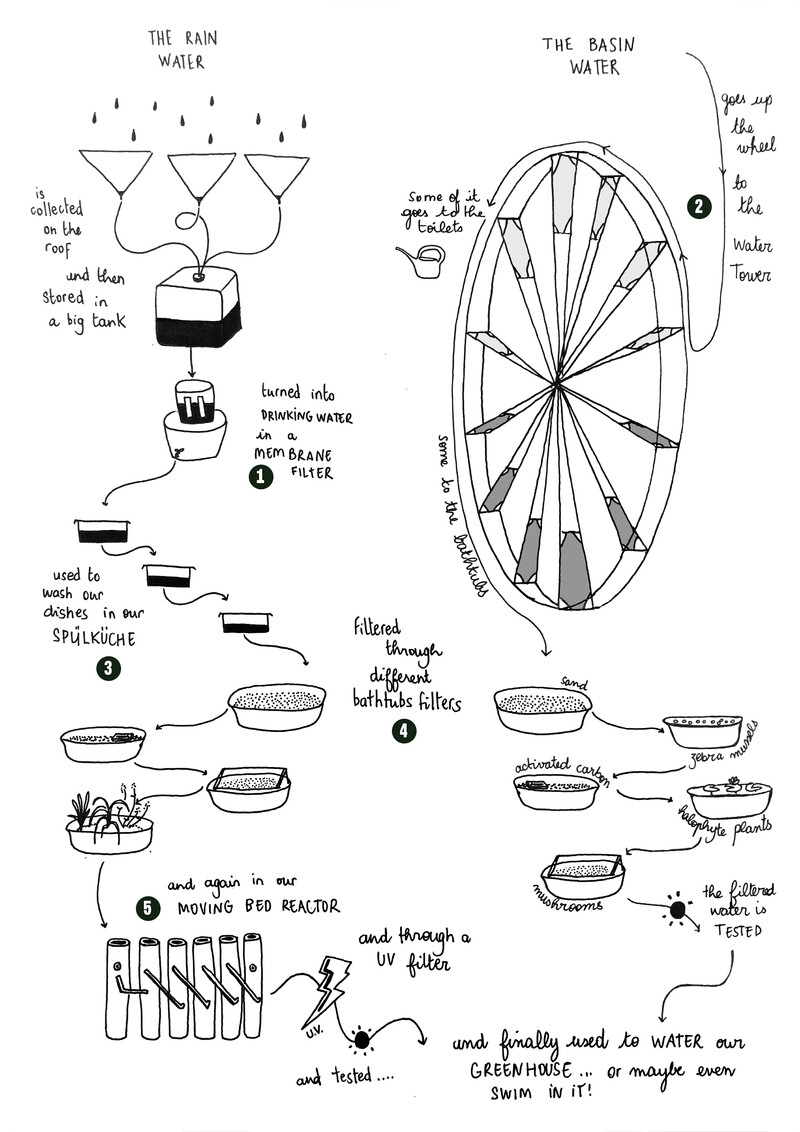

Water Filtration System

At Floating University, experimental water systems are constructed at every possible avenue. Water cascades down the laboratory stairs and spirals through a series of biological filters. Then, the filtered water journeys to the university’s kitchen, bathroom, auditorium, and greenhouse.

The filters are made out of plants, mushrooms, biofilms, sand, activated carbon, molluscs, and bacteria. They are located in a “spiral of bathtubs,” a membrane filter, and a moving bed reactor.

The spiral of bathtubs consists of nine bathtubs suspended from the ceiling of the Laboratory Tower. The membrane filter turns rainwater into drinking water and provides water for washing dishes. Finally, the moving bed reactor filters the university’s dirty dishwater so well that it is clean enough to irrigate the greenhouse, which grows thirty-five varieties of tomatoes from across Europe.

Water Qualities

Four different types of water are available at Floating University to experiment on:

Rainwater takes a six-kilometre skydive. On its descent through the urban atmosphere, it absorbs particulate pollution, sulphur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides. This tainted rainwater spills off the roofs of the university buildings and funnels through a collection system for reuse.

Basin water comes from rainwater that lands on the Tempelhof Airport building and airfield as well as on Columbiadamm road. Currently, this tonic of automobile oil, vulcanized rubber, cigarette chemicals, and other trash drains into the large open-air basin where Floating University “floats” and then drops into the canal system and flows to the Spree river.

Greywater is water that becomes “dirty” when it is used. There are various “shades” of greywater. For instance, greywater from the university’s offshore kitchen is laden with grease, fat, and food particles, while greywater from bathroom handwashing is laced with E. coli bacteria.

Blackwater is the most delicious. Produced by toilet water’s interaction with human waste, blackwater is full of nutrients for plants as well as pathogens. It is possible to use aerobic decomposition to turn blackwater into fertilizer and anaerobic digestion to create methane gas for cooking.

Water Cycles

How might our participation in urban hydrology nudge society toward an ecological balance?

How will we adapt our practices to rapidly changing cities and a rapidly changing planet to keep water affordable and abundant?

How can we be radical dreamers of utopia while keeping our feet on the ground—or in the water, as it may be?

See Connections ⤴