- 09.0Cover

- 09.1Because You Know Ultimately We Will Band A MilitiaXaviera Simmons

- 09.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 09.3Four Movements of DiffusionSophia Jaworski, Zoë Wool

- 09.4Water Filtration System: Floating University BerlinKatherine Ball

- 09.5Looking for a CureIrmgard Emmelhainz

- 09.6Theory of IceLeanne Betasamosake Simpson

- 09.7Legible Motivations: "Not Everything is Genuine"Nehal El-Hadi, Mark V. Campbell, Elicser Elliott, Charles Officer

- 09.8As if our Future Past Bore a Bad AlgorithmLiz Howard

- 09.9The Neurocultures Collective: Co-creating Moving Images

- 09.10ReceiptsImmony Mèn, Lilian Leung

- 09.11Weaving a Local, Grassroots WebJoy Xiang

- 09.12The First ChapterJacob Wren

- 09.13Glossary

Legible Motivations: "Not Everything is Genuine"

- Nehal El-Hadi

- Mark V. Campbell

- Elicser Elliott

- Charles Officer

The archives can take many different forms and behave in many different ways. They can be material or digital, selective or undiscriminating, regulated and uncontrolled. They can be housed online, or in buildings with security and climate control. But these aren’t the archives I’m most interested in—the archives I prefer to work with the most are messy with unclear boundaries, maintained by informal infrastructures, catholic in their criteria, fluid in their scope, and responsively open to those interested in them. I’m drawn to the ways in which these repositories are managed and accessed, the ways in which order emerges through patterns.

When I was asked to convene a panel on “diffusion,” I pictured ideas, images, languages, stories moving from areas of high concentration into those of lower concentration. This year has seen these flows happen organically and politically, but we’ve also watched as the conditions of our Black lives have contrived the dissemination and distribution of our emotions and narratives. I thought of the work of filmmaker Charles Officer, DJ and academic Mark V. Campbell, and artist Elicser Elliott—three Black men in film, music, and the visual artists—and the ways in which their work has provided reference points for my own understanding of Blackness in Toronto.

I’ve taught Officer’s music videos, documentaries, and films in university classes looking at social policy, storytelling geographies, and critical media. Campbell’s North Side Hip Hop Archives project both confirms historical legacy and celebrates Canadian contributions to a global cultural phenomenon. Elicser’s murals are some of the most recognizable in Toronto, and his work enlivens neighbourhoods around the city—I don’t know what kind of city Toronto would be without his art.

I brought them together for a conversation about the effects and temporalities of their work, most significantly as Black artists engaged in cultural production during a time when to be Black and alive is to be insisting on Black life. The conversation took place online: Campbell and Elliott were in Toronto, and Officer was in Winnipeg, MB, where he was working on a television series.

Nehal El-Hadi: I wanted to start with why you do the work that you do, and who you do it for.

Charles Officer: I felt like there was a massive gap. It’s a choice: you can either be in front of the camera or you can construct the stories. I felt like it was important to focus my energy on learning how to create the canvas that would allow talented Black people to work on this canvas. I felt there was this really important space of archiving our stories cinematically. There’s a not a lot of space that we’ve been allowed to occupy in this particular industry. I wanted to change that, one story at a time.

When I got into film, “Who’s your audience?” would always be the question. “Who do you want to reach?” And I realized—very quickly—what they’re trying to get you to do is make something for all the white folks. And if my work wasn’t speaking to them, it wasn’t valid. You can make something for an audience member from your family, someone who you love, who’s close to you, that you want to speak to. I often make these films for my nieces and nephews. That’s my audience. My mom. My aunts, my uncles—you know? Because they are reflections of my community, and I try to personalize it that way. And if I speak to them, the audience is actually larger.

Mark V. Campbell: My audience has changed over the last decade. When I started doing [the North Side Hip Hop Archives], I wanted to create resources for students and educators. Now my audience is the architects and pioneers of hip hop, trying to get them to see their legacy and to historically contextualize their achievements so that they can understand what they achieved. In the little tiny context that we live in, we may not see our value and our impact. But when you zoom out, our speech patterns have completely transformed North American culture, even if we don’t get credit for it. I try to do this kind of work to give people a larger context in which we can understand our value better.

Elicser Elliott: I’m an artist, and at least part of my duty is to talk about my day and times. That’s why I [paint murals], to educate the passer-by. If the person doesn’t know ackee and saltfish, let’s say, I put it in there, and they’re like, “What is that? Is that scrambled eggs?” No, that’s ackee and saltfish. So they go home, they research and find stuff, little tidbits to take away.

Especially my work on the street, for my community, for my surroundings, for the props getting up. It’s turned into more like I’m talking to the community. When I do a big mural, it’s usually funded by a grant from the city, so I have to encompass everybody. So sometimes it breaks down to taking the whole idea of the community and putting it in the mural, but somewhere in there, there’s the Black perspective. That’s my audience, sometimes.

Then when I’m just painting for myself, I tend to just go right out there. I can get really literal because I paint figuratively. But I try to not do it in the literal sense, so the viewer interprets it how they want to interpret it, instead of me pushing the full narrative on them. If they can see it from their perspective, it sticks with them a bit more.

NE: Have you ever found your work in places that surprise you?

MVC: I love libraries, but I don’t know nothing about the library sciences. What’s surprising to me is that the US Library of Congress hit me up: “Can you come talk about North Side Hip Hop?” And I’m like, “What am I going to tell you guys—you’re the Library of Congress. You should know everything there is about preserving.” It shocks me, because not only am I completely intimidated to go talk to archivists about this work I’m doing without training, but, in my mind, if they had valued Black life, I wouldn’t even need to exist. The work that I’m doing wouldn’t need to happen. It seems really curious to me that people are really interested once you start doing the work without the resources or the infrastructure. I think that’s the most surprising place that the work has shown up. I’m not doing anything radically different than anyone else in the archival sciences. I’m just storing it, preserving things, and talking about them. But it seems like there are other groups of people that pay attention.

CO: Unarmed Verses (2017) going to South Korea in 2018 [for EBS International Documentary Festival] was eye-opening. There’s this idea of the struggle of those who live in a lower income bracket, but it was surprising that the film—about this young twelve-year-old Black girl in Villaways here in Toronto and her experiences—resonated with so many people in South Korea. I’ve always known that’s the amazing power of cinema, the reach of it.

I was having a conversation with a guy blatantly telling me that he’s a racist, and then I’m in an audience that’s embracing my film. The experiences are interesting because he doesn’t know that I’m a filmmaker while I’m there [in person], but it’s amazing what that conversation would have been if he’d seen my film and then met me after. It’s always an interesting experience with cinema—what they assume you are, and then, when you’re in the cinema and they’ve seen that you’ve made that work, how they treat you. It’s fascinating that way.

NE: Elicser, what’s resonating for you?

EE: It’s being in different scenarios and the idea of: How do you come off without the context of your work? That’s a thought a lot of artists sometimes grapple with, I think.

NE: How do you grapple with it?

EE: I don’t know. There are situations where you’re in one arena where they’re talking about your work, and they’re speaking about it in this way, and you try to go to another place, and you’re treated in a different kind of manner. It’s like [Jean-Michel] Basquiat trying to catch a cab after the show. It seems like everybody treated him one way in the gallery, but as soon as he stepped out of the gallery, he was looked at in another way.

NE: This is something that I’m sure you guys are dealing with: How do you move through the fact that your work comes into demand in the wake of tragedies? How does it affect the way that you think about its production and dissemination?

MVC: I always get phone calls from the media when there’s a shooting or they want an expert opinion about a rapper. And I always say no to them. And these horrible articles still run, and they usually get an American perspective on something that happened on Spadina. As I do the work, I start to close down the legibility of the work that I’m doing, so it’s legible to the people I want it to be legible to. I’m thinking about Charles making films for his family members. This is part of our blessings. We’ve always been speaking in code, and hip hop being cryptic is an extension of that.

The work always gets taken up at the worst times. Outside of saying no to discussing your work with certain people, I also make sure that the work becomes legible in certain kinds of ways. When I’m talking about mixtapes or something like that, then I’m speaking to certain kinds of people who know about these things. Opacity.

NE: The right to be opaque.

MVC: Yup.

CO: We’ve been doing our work for the reasons that inspire us, for our communities, for our people, and for our own survival. These tragic moments that happen—we’ve been experiencing them for a long time. And these last ten or twelve months have been crazy. But we’ve always been here. We’ve been talking about things for a long time. I kind of equate it to the idea of blood money. Suddenly, there’s this situation where organizations and institutions want to play some sort of role in our well-being. There’s been centuries of them abusing us. I’m not fooled by the idea that now they’re suddenly on our side and they want to see us prosper. Every time something happens, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been asked to do these things that I have to vet: Who’s asking me and why? And for my own well-being, there’s rarely the consideration that we’re actually experiencing something. I’ve had moments where I’ve turned down these requests and I’m getting a backlash, like I’m not trying to participate. It’s like: Yo, I’ve been participating. You haven’t been participating. So don’t put that on me, not now.

There is that advantage right now for Black artists to finally get their shit done and take advantage of this moment. But I don’t think that should be at the cost of your own mental health, your own well-being, or against your principles. You know what I mean? All this to say: through this whole process, you have to understand that not everything that is coming out of this right now is genuine.

NE: Thank you, Charles. Elicser, how do you make the choices in your career that you do?

EE: It feels sometimes like there’s an underneath reasoning why they’re picking you for a particular gig or campaign. And you feel weird about that. I got a request to put my work and images on one of these e-cigarette campaigns—basically, put your pieces on e-cigarettes for the preservation of Black life. I just didn’t even answer that email. But the fact that emails like that could go around … I just don’t care to have a say on it.

NE: I wonder if you all think about the temporality of your work—how your work exists over time. Elicser, we’ll end with you, because I’m also interested in the ways that your work is put up and sometimes painted over. First, Mark: How do you think about temporality and distance over time for your work?

MVC: March was the ten-year mark for the North Side Hip Hop Archive. If something happens to me, what happens to North Side Hip Hop? It has forced me to think about how to become a platform for the work, and to become infrastructure for our community. It feels like I’m doing public education work and also creating not just the language but also the platforms so that people can begin to archive their own work. I think about temporality all the time. With digital archiving, I constantly keep my finger on the pulse. If I disappear, what happens? Is North Side in the cloud somewhere? Will it always be accessible? What happens to the physical materials? How many students have I trained to take over? How many people know how to do this with nuance? I think about that more than I think about the things in the archive. Some people want to be encyclopedias of information, and I’ve got to figure out how to make a digital asset and what an NFT looks like and what does that mean for archiving Black stories going forward, if we’re trying to do share splits on songs that never got copyright, or where labels went under.

CO: One of my inspirations getting into filmmaking was that cinema actually immortalizes. And what I understood was that these ideas, well after you’re gone, will remain. It’s one of those mediums that—whether or not it was going to be true for me—I felt was an important space. It had a natural connection to archiving our stories. But for myself as well as my own work over these years, I had to realize that I made my first film in 2000. Last summer, the University of Toronto reached out about archiving my work, and they actually expressed that they don’t have Black filmmakers in their archives. There’s a young filmmaker working with our small company [Canesugar Filmworks] who’s going to be helping to put that material together. It also triggered her mind about how she’s going to be taking care of her stuff as she’s moving forward, so it gives her a nice pathway into preparing to archive her own work.

For me, it’s the “each one, teach one” vibe: Make sure that the next generation is inspired, and they’re continuing that lineage of work. That’s the way that you can contribute.

EE: We already have that in the graf community, the sense of archiving. If we’re going out on a mission to go paint trains somewhere at three in the morning, you better have good cameras. Like, right after—take a flick and get this, coz the piece is going to roll away. But in the sense of the city and painting murals, sometimes pieces fade or whole buildings get built in front of my pieces.

Preserving the work of Black artists appears to take on new urgencies when the infrastructures that promote and support their art rely on a market that mythologizes exceptionalism and rewards tokenism. But none of these circumstances are surprising, exceptional, or new, and treating them as such challenges the authenticity of the work that Black artists somehow manage to produce consistently and in defiance of what they have to contend with on the daily.

See Connections ⤴

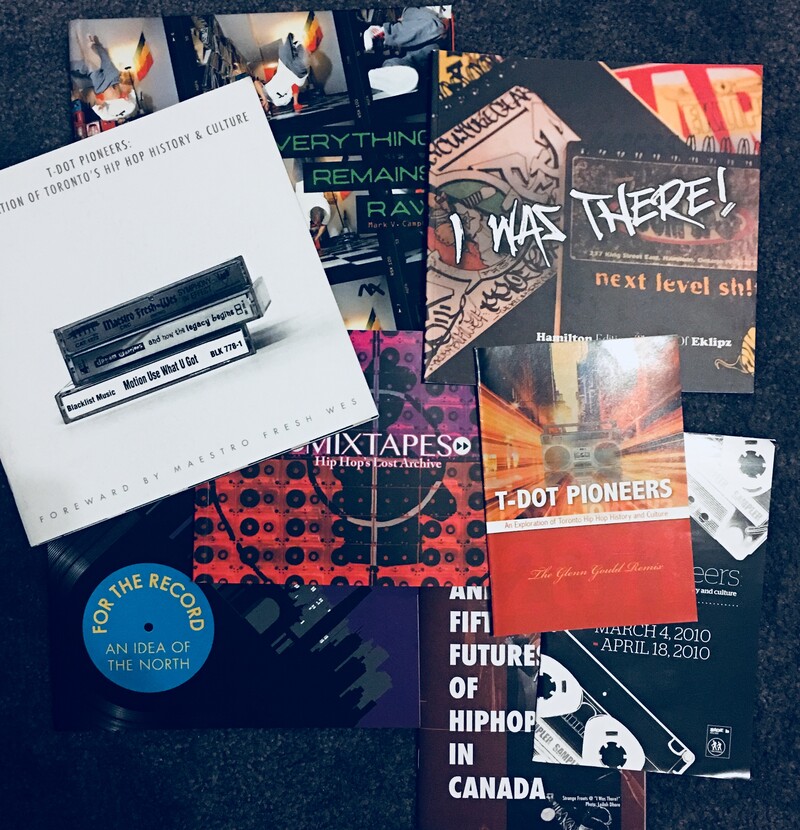

Mark V. Campbell (aka DJ Grumps), founder at Northside Hip Hop Archive, is a DJ, curator, and scholar. As a co-founder of the Bigger than Hip Hop Show at CHRY 105.5 FM, Mark DJed and hosted the show from 1997–2015, and served as a Member of the Board at the Ontario Arts Council from 2015–2018. As a curator, Mark has organized exhibitions related to Canadian hip hop, including the T-Dot Pioneers trilogy, Mixtapes: Hip-Hop’s Lost Archive, …Everything Remains Raw: Photographing Toronto Hip Hop Culture from Analogue to Digital, and For the Record: An Idea of the North. As a scholar, Mark has published widely in various academic journals, and his co-edited collection We Still Here: Hip Hop North of the 49th Parallel was released in 2020 by McGill-Queen's Press.

See Connections ⤴

Elicser Elliott is a Toronto based aerosol artist whose creations adorn the cultural landscape here and abroad. An integral part of Toronto’s street art community for over a decade, he has been recognized and praised by both street and fine art collectors all over the world. His work has been featured in many publications and hung in prestigious galleries like the Art Gallery of Ontario and Royal Ontario Museum. Although he is a Montreal native, Elicser grew up in St. Vincent. On his family’s return to Canada, he was introduced to street art while attending the Etobicoke School of the Arts. However, he had not seriously considered art as a possible occupation until he had a discussion with a guidance counselor who encouraged him to study animation at Sheridan College.

See Connections ⤴

Charles Officer is an acclaimed writer, director, producer and founder of Canesugar Filmworks. A former creative director and graphic designer, his film works include the recent crime-noir Akilla’s Escape (TIFF 2020), and feature documentary Mighty Jerome. Officer’s Unarmed Verses cemented his distinct visual brand of storytelling, winning awards at Hot Docs and TIFF Top Ten Festival. From garnering record setting CSA Nominations for his debut feature Nurse.Fighter.Boy to his truth to power documentary The Skin We’re In, Charles is committed to amplifying diverse stories that integrate the arts. He is a founding member of Canada’s first Black Screen Office, and serves on the board of trustees at the AGO and Reel Canada.

See Connections ⤴