Let’s be honest, the weather helped _ NATO

This image is presented in the exhibition Unruly Archives, curated by Amin Alsaden. The exhibition brings together artists whose work employs archival traces to underscore the global footprint of war and organized violence, and speak to dimensions of conflict that are usually overlooked or deliberately suppressed. As such, the images challenge the correlation between conflict and specific regions, particularly South West Asia and North Africa, while highlighting international complicity through a history of colonialism as well as recent political meddling and military interventions. Organized violence destroys not only human beings and their environments, but also has a lasting, traumatic, and often invisible impact that brings to the fore questions of memory, representation, culture, nationhood, and belonging.

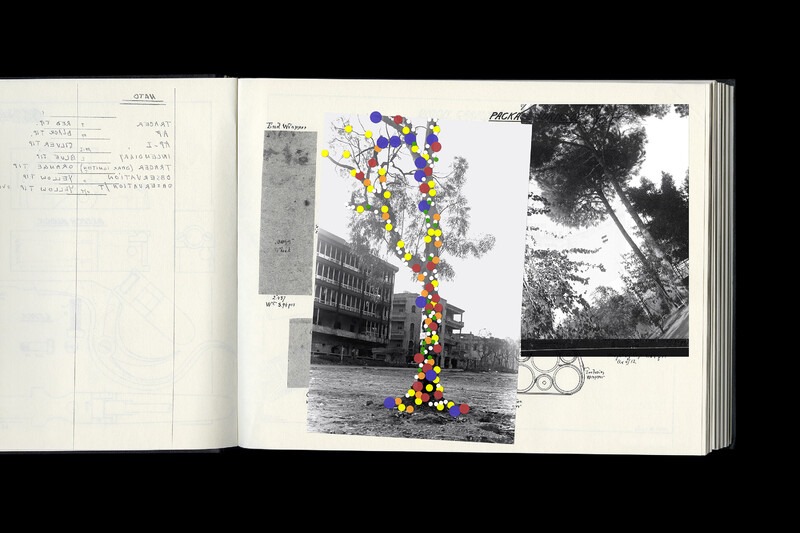

Between the years 1989 and 2004, Walid Raad pursued a multipronged project entitled The Atlas Group, researching Lebanon’s contemporary history, with a focus on what came to be known as the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990). In the archive he produced, consisting of text, audio, and visual documents, the boundaries between reality and fiction are blurred, conjuring and further complicating the manner in which this conflict is remembered. In the series Let’s be honest, the weather helped, from which this image is extracted, Raad produced plates that emphasize how this “civil war” was sustained through international interventions, evoked here in the constant supply of weapons that tore the country apart. This image speaks to the fact that war not only affects human beings and cities, but also targets the environment, decimating flora and fauna—one side of contemporary warfare that is usually disregarded. The work raises questions about the politics of remembering, particularly how archives are constructed, their claims to neutrality and truth, and, therefore, their inherently problematic nature.

The following statement by the artist accompanied this series as it was deposited into The Atlas Group Archive: “Like many around me in Beirut in the late 1970s, I collected bullets and shrapnel. I would run out to the streets after a night or day of shelling to remove them from walls, cars and trees. I kept detailed notes of where I found every bullet and photographed the sites of my findings, covering the holes with dots that corresponded to the bullet’s diameter and the mesmerizing hues I found on bullets’ tips. It took me ten years to realize that ammunition manufacturers follow distinct colour codes to mark and identify their cartridges and shells. It also took me another ten years to realize that my notebooks in part catalogue seventeen countries and organizations that continue to supply the various militias and armies fighting in Lebanon: Belgium, China, Egypt, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Libya, NATO, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, USA, UK and Venezuela.”

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently closed.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.