This exhibition brings together artists whose works employ archival traces to underscore the global footprint of warfare and organized violence, and speak to dimensions of conflict that are usually overlooked or deliberately suppressed.

The war enterprise, rooted in the history of colonialism, genocide, and slavery, and sustained by extractive capitalism, is a force that has structured and continues to shape much of the world. Achille Mbembe, among other theorists, has reflected on the inextricable links between warfare and global politics, suggesting that democracy worldwide is increasingly embracing its double or nocturnal side, which embodies the same violent impulses that propelled colonialism over the past few centuries. Based on a spirit of enmity intent on annihilating the “Other,” Mbembe argues in Necropolitics that governments today rely on war as a survival strategy, which produces a vicious cycle that often ravages the non-West, or minority communities in the West.

The exhibition calls attention to the fact that this war enterprise rests on the consumption of fossil fuels, which places oil-rich regions at the nexus of global ideological rivalries and fierce competition for resources. Although the Arab world, stretching from South West Asia to North Africa, is commonly reduced in Western media to a volatile zone, warfare in this part of the world tends to encapsulate the imperial dreams of dominant powers and their insatiable appetite for oil (or their desire to quell existential threats, typically in the form of militant Islam). The exhibition confronts the problematic correlation between conflict and the Arab world, underlining international entanglements in the tribulations of this geography, through a history of colonialism as well as ongoing political meddling and recent military interventions.

Organized violence, the exhibition affirms, destroys not only human beings and their environments, in this and other regions, but has a devastating, multifaceted, and lasting impact globally. Ongoing warfare serves to obfuscate pressing issues such as environmental degradation, which in turn exacerbates the economic and social disparities plaguing the world, leading to unprecedented apathy and polarization. More importantly, in Arab countries and elsewhere, violence also leaves an invisible stain—the contours of which may be detected within archives—touching on questions of memory, representation, culture, nationhood, and belonging.

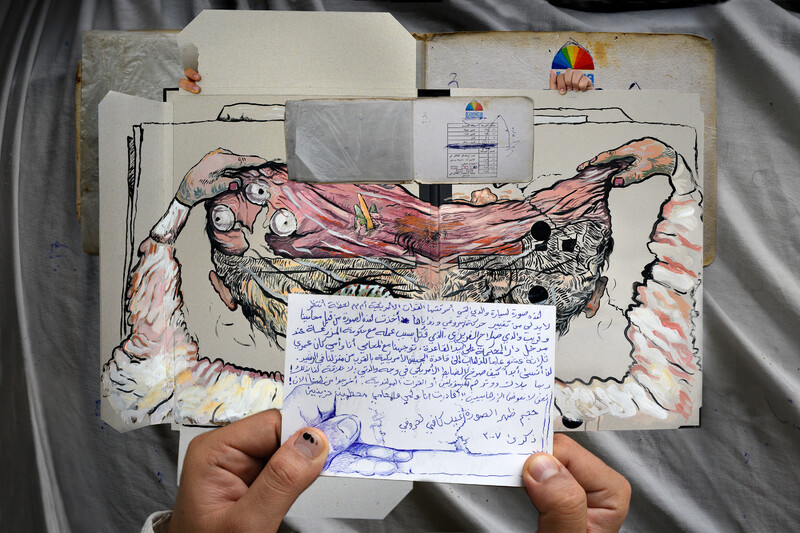

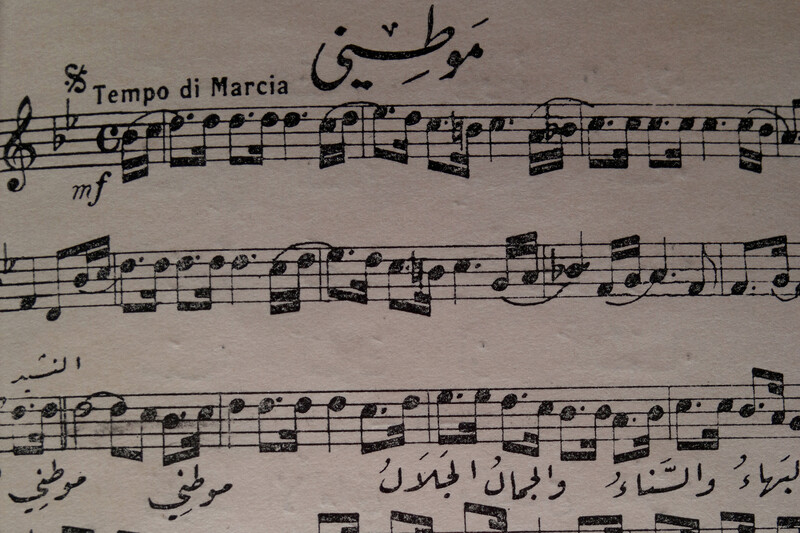

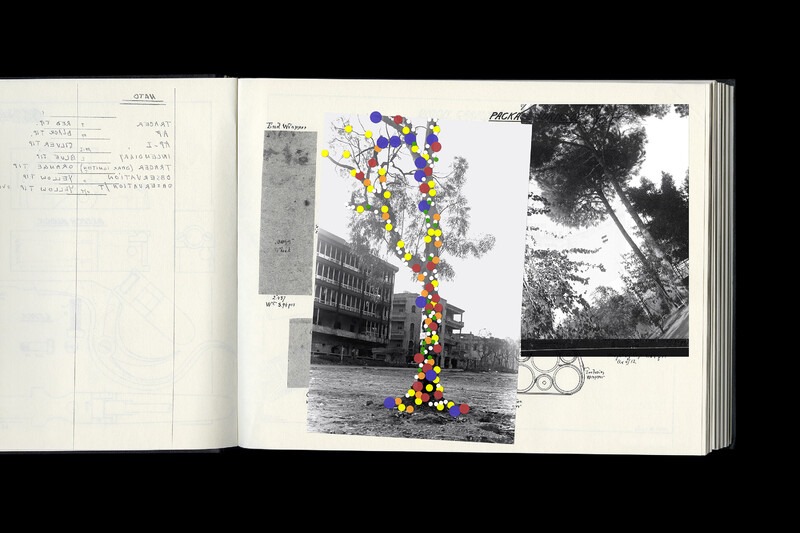

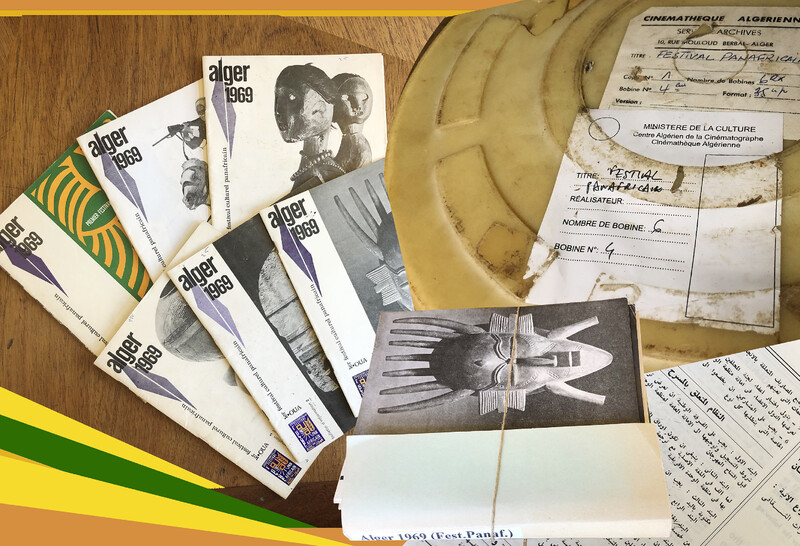

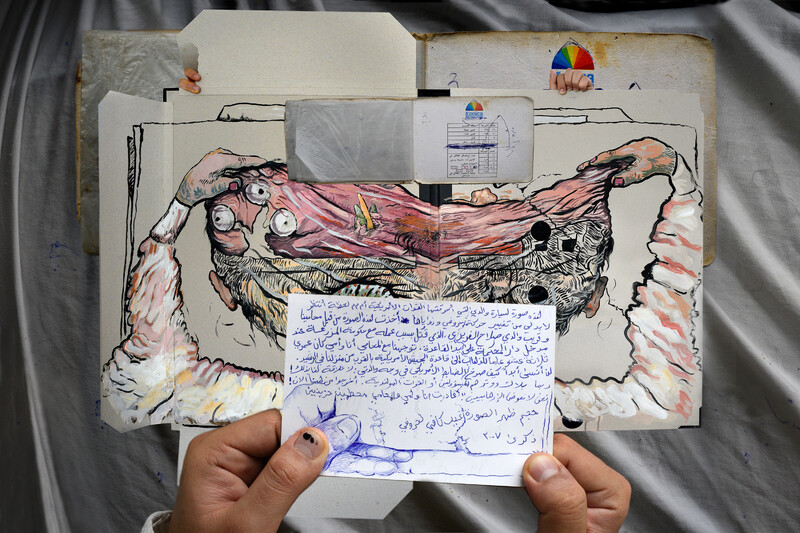

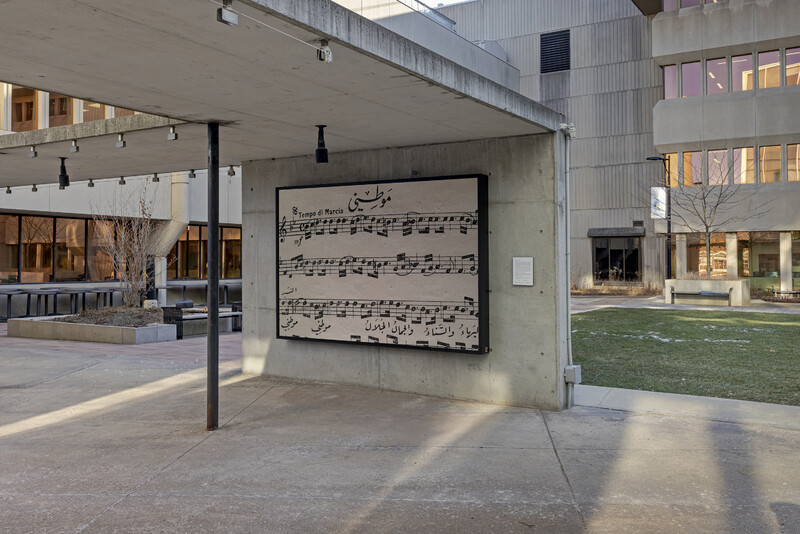

The participating artworks address the multiple, and often hidden, aspects of organized violence, and their far-reaching repercussions. Covering myriad parts of the Arab world, across different time periods, addressing varying guises of conflict, and gesturing toward numerous manifestations of archives, these works also blur boundaries between past and present, here and there, them and us. Zineb Sedira’s work conjures the violent legacy of colonialism, but also the transnational solidarities and liberation movements it sparked across the non-West, through reflections on family and post-colonial archives. Emily Jacir’s work tackles how colonialism and armed conflict led to the dispossession, displacement, and loss of cultural property, evidence of which the artist found in misappropriated archives. Walid Raad’s work explores the inherent complexities and contradictions encountered when remembering local conflicts, partly inflamed by international interests, through assembling an archive that deliberately conflates historical facts with fiction. And, Ali Eyal’s work evokes the deep traumas left behind by recent foreign interventions, and the open wounds that continue to torment the region and its diaspora, which he captures by recollecting personal memories and delirious dreams.

Directly or implicitly, these artists raise polemical questions about the ways in which violence casts dark shadows onto archives, and think—in expansive and speculative ways—about the challenges of remembering a distressing past. They ask, in other words, how history is written, why, and by whom. Indeed, the space of the archive emerges in all the participating works, in various modalities: conventional, institutional, and state archives; personal, private, and community archives; invented, imaginary, and fictional archives; lost, displaced, and pillaged archives; covert, occluded, and non-existent archives; resistant, alternative, and counter archives.

This profusion of archives also begins to indicate the incommensurability between the scale of tragedy experienced in places and communities that have endured conflict, and attempts to account for the deep pain that remains largely obscured—by contemporary media and geopolitics, which habitually conceal international complicity in bringing about these catastrophes.

In their plurality and open-endedness, these are atypical, unruly archives: disruptive, loud, and impossible to contain. The events, narratives, and truths they communicate refuse to be silenced, returning relentlessly to haunt the world, demanding attention and room in our collective consciousness. Demanding justice.

—Amin Alsaden

Unruly Archives

Curated by Amin Alsaden

Part of Crossings: Itineraries of Encounter, the 2021–22 Lightbox Program

Attunement Session

Installation Views

Interpretive Video

Educator-in-Residence Shalon T. Webber-Heffernan leads a tour of Unruly Archives on University of Toronto Mississauga campus.

- Curator

- Amin Alsaden

- Attunement Session

- Anna Jayne Kimmel

- Dana Olwan

- Rijin Sahakian

- Rasha Salti

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently closed.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.