patricia kaersenhout’s series Of Palimpsests & Erasure (2021) is the second in a sequence of image sets that comprise the exhibition Overseeding: Botany, Cultural Knowledge, and Attribution. Overseeding is the practice of spreading grass seed for the recolonization of lawns, land that would have had its own botanical communities. Turning the settler practice back on itself, the exhibition seeds over monocultural understandings of the origins of agricultural, botanical and herbal knowledge, returning pre-imperial ideas and diverse authors to the space. Palimpsests are writing materials, such as parchment, that have had text erased so that the writing surface can be reused, but continue to hold traces of previous inscriptions. Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname), a book of illustrations of insects with their host plants, self-published by Dutch naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian in 1705 is the point of departure for patricia kaersenhout’s featured work.

Maria Sibylla Merian made a life of unconventional choices, for a Dutch woman living at a time when it was believed that women, by their nature, were incapable of producing scientific knowledge, and were typically limited to domestic duties. Self-initiated, Merian studied the lifecycle of caterpillars, observing them in their natural habitat and by breeding them. She recorded her findings with skillful detail, in striking watercolour paintings, publishing three collections of engravings between 1675 and 1680. In middle age, she divorced and decided she would travel to Suriname, a Dutch colony since 1667, to continue her study of insects, with one of her two adult daughters assisting her. The journey of over two months on churning seas, in cramped conditions, with deteriorating food quality was one that she had the freedom to choose or to refuse.

Being raised in a family of business owners, engravers, publishers and artists afforded the naturalist with the advantages of exposure, tutelage, and access, including to books on natural history. She made her way to Suriname with connections to plantation owners there, supported by a grant from the city of Amsterdam and proceeds from the sale of her artworks, enough that she planned to stay for five years. And as a white woman, she was free to enslave others to service her passion.

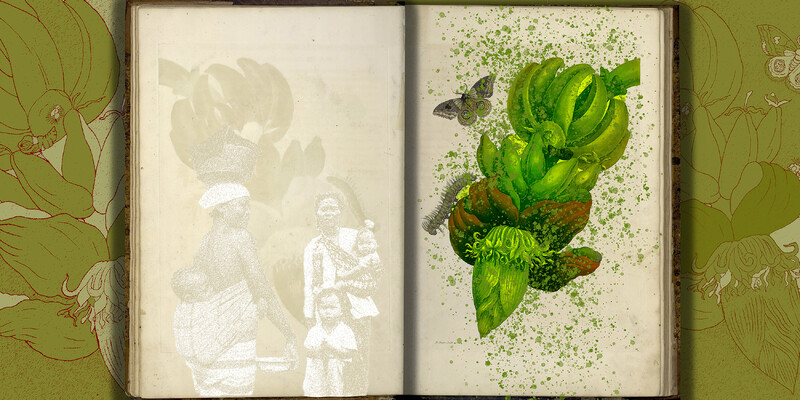

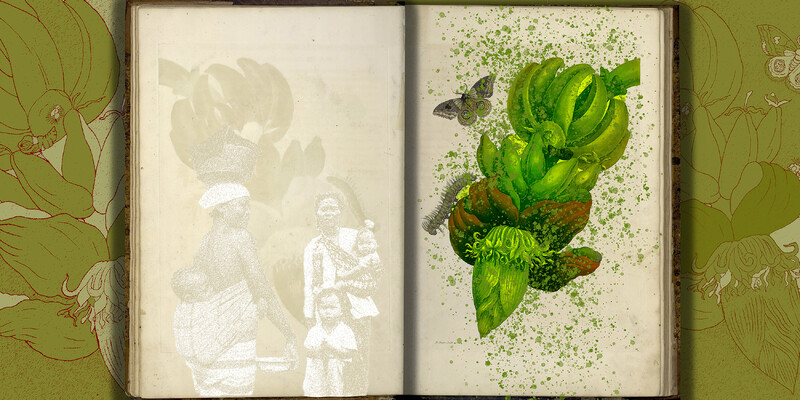

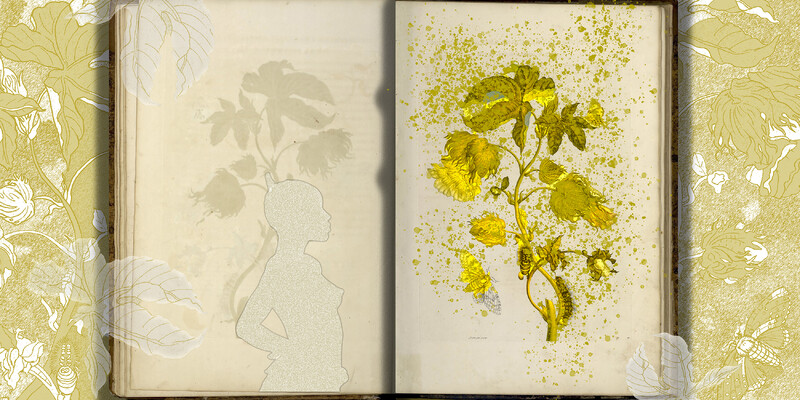

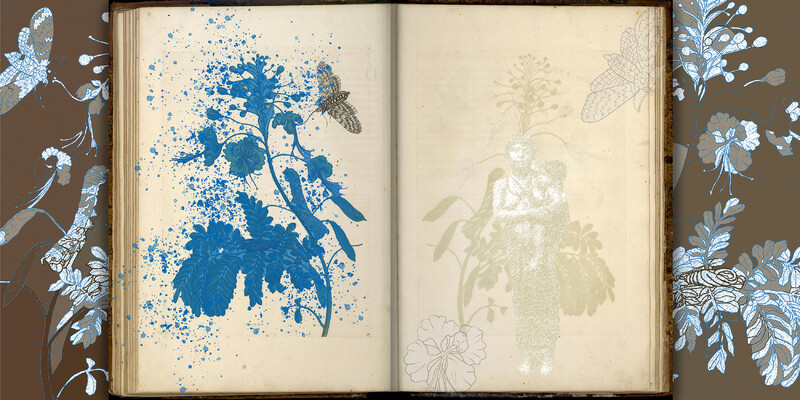

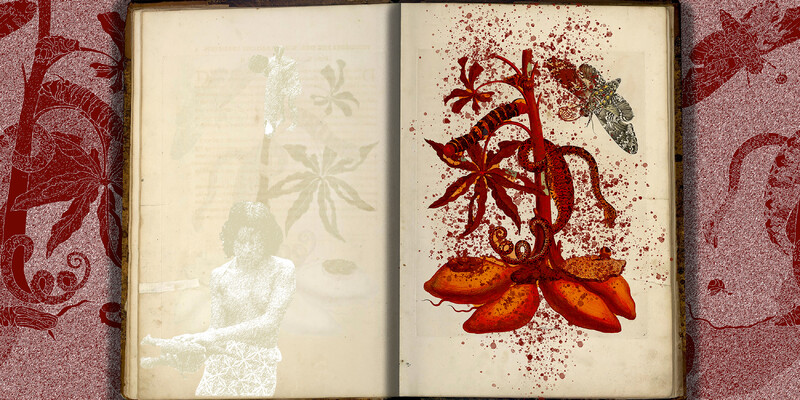

kaersenhout’s images resemble an open book; however, the side-by-side pages represent the recto (front) and verso (back) of the same illustrated page. A response to how the artist experienced Insectorum Surinamensium—Merian’s illustrations on the recto, perceptible on the verso. Selected drawings by the naturalist have been shaded over by kaersenhout, whose pigments complicate readings of the original images, dulling the beauty that has distracted from the ugly realities that Merian’s achievements stand upon. On the page representing the verso, a faint earth toned version of the same insect and host plant is joined by a figure of a woman, that is decidedly not Merian. The artist explains “The bodies of the women 'disrupt', as it were, a dominant history and thereby at the same time claim a place in a history that has actively wiped them out.”

It's unclear whether Merian was given or purchased enslaved people, but she enjoyed the benefits of being an enslaver, extracting physical labour hand-in-hand with Indigenous and African ethnobotanical knowledge, developed over generations before Dutch arrival. The women imprinted onto kaersenhout’s versos likely share resemblances with those whom Merian referred to as “my Indian” and “my slave,” diminishing their identities in the notes written alongside her visual studies. The women she tasked with the toil of creating a path for her research received no additional recognition. In her own words, “because the forest is so densely grown with thistles and thorns, I had to send my slaves ahead of me with axes to hack out an opening for me,” and “my Indian brought back [collected specimens] to my house and planted.”

In the preface to Insectorum, Merian mentions her distaste for “the company of people,” emphasizing her lone and chosen servitude to the study of flora and fauna. The naturalist’s work was inarguably dependent upon being accompanied by people—enslaved Africans and Indigenous Lokono and Kalipuna, who had been living on, and knew the land she desired to glean from. A great deal of knowledge Merian is credited for arrived to her through transfer. Perhaps the women, hearing that their enslaver intended to stay no longer than five years, strove to bring her attention to evermore captivating things in hopes that they wouldn’t soon be taken with her to live or re-live the terror of being trafficked across the ocean, when Suriname no longer held her thrall. They could tell by the way their labour, caring for the house, and for Merian and her daughter freed her to absorb herself in painting, and by her eagerness to be shown the ecology of co-existence between local insects and plants, that she could scarcely do without them and would wish them to continue tending to her.

Neither she nor history credited the Indigenous and Black women for the botanical knowledge they shared, and she published. Characteristically, with identities omitted, Merian wrote of being taught about Flos Pavonis or Peacock Flower, which is highlighted in #4/8 of kaersenhout’s series: “The Indians, who are not treated well by their Dutch masters, use the seeds to abort their children, so that they will not become slaves like themselves. The black slaves from Guinea and Angola have demanded to be well treated, threatening to refuse to have children. …They told me this themselves.”

The significance of this teaching is greater than that of marginalia for Merian's illustrations. It could be understood as a message to the Dutch woman, who ship’s records show brought a captive unnamed Indigenous woman back to Holland with her. Communicating to Merian, who rested in the confidence that colonial laws entitled her to ownership of persons, that she would not have totality. Sipping tea steeped with the seeds of Peacock Flowers, the women could disrupt enslavement. Their appreciation of the flaming yellow and red flower escaped the comprehension of Europeans, whose limited perception deemed it to be an ornamental shrub with “no known [medical] virtues” (Hermann Boerhaave, 1727, Historia plantarum). Since before European arrival, Amerindian women used the plant to regulate their menstrual cycles and fertility. In kinship with the enslaved African women, they shared their medicinal knowledge. The relationship the women had with the flower demonstrates the complex understanding they held regarding their positions within the dynamics between women’s reproductive health, herbalism, the flow of colonial capitalism and power.

In recent years, interpretation of the events of Merian’s life and research has grown, bestowing her with latent recognition and validating her as a botanical and natural history illustrator, entomologist, ecologist, researcher, writer, publisher and explorer, who was dismissed and belittled under patriarchy. Without a doubt, she faced tremendous gender-based discrimination, against which she produced valuable and exquisite visual documents, fulfilling her creative and intellectual drives—while preventing such actualization for others. To privilege Merian’s achievements without laying bare her extractive methods, and bringing the individuals who contributed to her success into the light, is to reproduce historical harms.

Only two years had passed in Suriname when Merian experienced a lingering illness, possibly malaria. Receiving urgent instructions to bring things living and dead to add to her already sizeable cache, was an indication to the women that she was preparing to leave. Perhaps sensing that their time in Suriname would end with hers, they strategically told her of food plants that were important to them, influencing her to both memorialize the plants’ likenesses and bring them across the ocean for cultivation. #2/8 in kaersenhout’s series is the Loweman Bakba (runaway banana) that had come to Suriname from Java (Indonesia), a place the Dutch had begun to settle. The banana had also been successfully cultivated by the Maroons of Suriname. #5/8 is the Cassava root, a staple food for Indigenous people, enslaved Africans and Maroons. The fruit and tuber are two of the ingredients in Heri Heri, a dish that would later symbolize emancipation day in Suriname (July 1, 1863 though in reality it took ten years for the enslaved to be freed in earnest). The celebratory day, observed in both Suriname and the Netherlands, is also called Keti Koti, Sranantongo or creole for "the chain is cut" or "the chain is broken.”

Caesalpinia pulcherrima is the Latin name Europeans assigned to the Peacock plant, obscuring the pre-existing Amerindian name that would have held traditional knowledge within it. The Peacock plant’s brilliant cupped flowers bloom in clusters that transform into brown seed pods, and finally, when ripened, burst forth to scatter seeds that are respected for their medicinal value. A plant that women have used to disrupt violent racial capitalism could also conceivably be called Keti Koti.

—Su-Ying Lee

Of Palimpsests & Erasure

Curator: Su-Ying Lee

Part of Overseeding: Botany, Cultural Knowledge, and Attribution, a three-part lightbox exhibition on UTM campus.

Image Set

Public Program

Installation Views

- Artist

- patricia kaersenhout

- Curator

- Su-Ying Lee

Proudly sponsored by U of T affinity partners. Discover the benefits of affinity products!

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently closed.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.