- Info

How to Read the Reader

- Feb 14, 2025

The Agency of Walking

- Jan 21, 2025

Groundwater

- Jun 25, 2024

QUIET PARADE: Precedent Projects

- Jun 18, 2024

Unearthing Stories: Tracy Qiu on Decolonizing Plant Narratives

- May 27, 2024

Resources and Research: Overseeding

- Mar 28, 2024

The Blackwood Index on Campus

- Feb 26, 2024

Building Interrelationships through Interpretive Text

- Feb 07, 2024

Listening is Our Ongoing Score

- Dec 06, 2023

To resist, to empower, to heal

- Nov 20, 2023

Queer Orientations for Future Worldmaking

- Nov 02, 2023

“The sex ed we have as teenagers is precarious”: A timely conversation between Lorena Wolffer and Kira Sosa Wolffer

- Oct 27, 2023

Readings and Resources on Palestine

- Oct 20, 2023

Difficult Art

- Jul 13, 2023

Gestures Toward the Miraculous: A Q&A with Erika DeFreitas

- Jul 06, 2023

“A toast! to you”: Create Your Own Meal of Choices

- May 30, 2023

Sense Encounters

- May 16, 2023

What brings you here? SDUK Readership Survey

- May 05, 2023

Here, Better, Now: Connections

- Apr 06, 2023

Here, Better, Now: Foundations

- Mar 03, 2023

Turning Points

- More…

What stories do we tell about plants, and who tells them? Which stories are overlooked, and why? How do these narratives influence culture, identity, and community? These questions were at the heart of the recent workshop Plant Provocations led by researcher, educator, and gardener Tracy Qiu. Developed alongside the lightbox exhibition series Overseeding: Botany, Cultural Knowledge and Attribution, curated by Su-Ying Lee, this program invited participants to share knowledge about plants and people from a decolonizing and decentering perspective. Attendees were encouraged to bring their own plants of significance, with additional plants loaned by UTM’s Teaching Greenhouse. For Qiu, plants serve as an accessible tool for discussing decolonization, which she defines as “visibilizing, acknowledging, and intervening in past, present, and ongoing impacts of colonization.”

Qiu opened by recounting her childhood on a peanut farm in China, her immigration to Canada, and her unexpected career path—from a degree in animation to a pivot towards horticulture. She was only the second racialized person to enroll full-time at the Niagara Parks Commission School of Horticulture, one of the few programs of its kind in Canada, emphasizing the lack of racial diversity in the field.

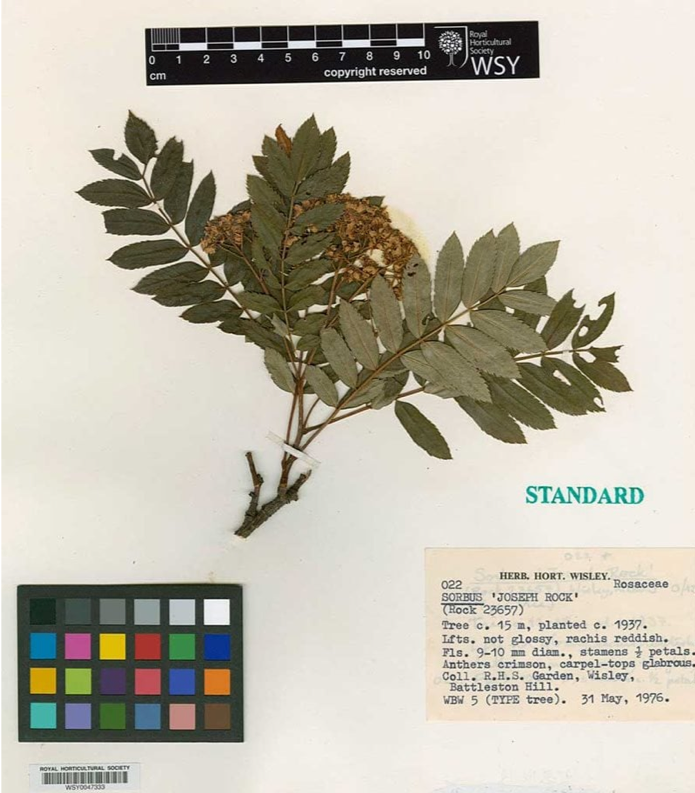

Qiu explained how art and plant science have long been intertwined, from the frescoes and reliefs of Classical Antiquity in Europe and Southwest Asia to the gelatin silver photo prints of the Industrial Revolution. Despite advancements in photography, plant illustrations remained crucial for identification due to the variability of photographs under different lighting and weather conditions. Qiu highlighted different approaches to plant representation in Western European and non-Western cultures: Western depictions often isolate plant specimens on a white page, exemplified by Sorbus “Joseph Rock,” named after the Austrian-American botanist who collected plant specimens and seeds in Asia for 30 years in the early to mid-20th century. By contrast, non-Western representations typically show plants in relation to their environment, as seen in Métis artist Christi Belcourt’s painting The Wisdom of the Universe, about which Qiu highlighted its accurate representations and identifiable species.

Drawing inspiration from patricia kaersenhout’s Of Palimpsests & Erasure, which exposes how Dutch naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian exploited the physical labour and ethnobotanical knowledge of Indigenous and African people to produce her book, “The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname,” Qiu further explored the significance of other common plants including:

- Toloatzin/toloache (Nahuatl), also known as thorn apple (Datura innoxia), which have been historically significant in Indigenous cultures and traditional medicine in Mexico. Despite suppression efforts post-contact, Datura species have maintained their importance and are also commonly cultivated.

- Leopard lily (Dieffenbachia species), native to Mexico, the West Indies, and Argentina, has a troubling history of being used as a tool to punish or silence enslaved people due to its toxic properties, which earned it the name Dumb Cane.

- Maguey, or agave (Agave species), native to Central and South Tropical America, holds sacred status in Aztec and Mexica culture. It is used to produce alcoholic beverages like pulque and tequila, fibers for ropes and clothing, and medicinal treatments for wounds and digestive issues. Symbolically, maguey is linked to fertility and resilience, featuring in rituals and mythology, particularly associated with the goddess Mayahuel, representing sustenance and adaptability.

- Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), native to South America played a significant role in ancient trade and cultural exchange.

- Papyrus (Cyperus papyrus), native to Africa, was crucial for making paper in ancient Egypt, marking a pivotal moment in written communication.

- Peacock flower (Celsalpinia pulcherrima), depicted in kaersenhout’s work, has a complex history, having been used as an abortifacient in traditional medicine by enslaved Africans and Indigenous populations in Suriname.

- Aloe Vera, native to Southwest Asia, is renowned for its medicinal properties. Its gel is widely used to soothe burns and treat various topical injuries. Additionally, the latex derived from Aloe is used as a natural remedy for constipation. Aloe Vera has a rich history dating back to ancient Egyptian medical texts.

Through these narratives, participants were encouraged to reconsider how plant stories shape and reflect cultural identities and communities, highlighting the importance of acknowledging overlooked voices and histories within the world of plants.