- 13.0Cover

- 13.1How to Read this Broadsheet

- 13.2Butterfly EffectsMaggie Groat

- 13.3what the river reveals: remembering like the waterCéline Chuang

- 13.4Dechinta | In the Bush: Northern Harvesting and Land-based LearningLianne Marie Leda Charlie

- 13.5Filling Spirits: Community-oriented Cuisine and GardeningRobin Buyers, Sienna Fekete, Sonia Hill, Camille Mayers, Vasuki Shanmuganathan

- 13.6Interview with OmehenThe Forest Curriculum

- 13.7Parasitic OscillationsMadhur Anand

- 13.8Msit No’kmaq: Deepening Relations with Mother EarthCarolynne Crawley

- 13.9Thinking with Black Ecologies in Educational ResearchFikile Nxumalo

- 13.10Peasant CVAsunción Molinos Gordo

- 13.11How Not to be ConsumedAimi Hamraie, Maria Hupfield, Zoë Wool

- 13.12Against RenewalChristina Sharpe

- 13.13Rooting in ExileMagdalyn Asimakis

- 13.14Glossary

How Not to be Consumed

- Aimi Hamraie

- Maria Hupfield

- Zoë Wool

Zoë Wool: Academic institutions are extractive spaces. But, as la paperson reminds us in the radical text A Third University Is Possible, they are always also more than that. Folded between their layers of bureaucracy, nestled between their conventional pedagogies and methodologies that conserve colonial and white supremacist forms of prestige and expertise, otherwise practices take root.

In fall 2021, I launched the TWIG Research Kitchen, a feminist research space devoted to experimental work on themes of toxicity, waste, and infrastructure across the social sciences and humanities. Praxis-oriented, we explore what convivial modes of research might be like. Formed in relation to disability justice, we try (and sometimes fail) to build models of scholarship that are sustainable and nourishing, rather than extractive and exhausting.

In hatching the Research Kitchen, I am lucky to have excellent examples to learn from, including Andrea Ballestero's Ethnography Studio, Aimi Hamraie's Critical Design Lab, Maria Hupfield's Indigenous Creation Studio, Max Liboiron's CLEAR lab, and Michelle Murphy's Technoscience Research Unit.

The Blackwood invited me to talk with two of these scholars about how we're re-figuring research, collaboration, and community involvement. The conversation below is an edited transcript of the really nourishing discussion I got to have with Aimi Hamraie and Maria Hupfield. Hamraie's Critical Design Lab is a collective of disabled designers, artists, and researchers currently spread across three countries exploring and making technology and media using a disability culture framework and approach. Hupfield's Indigenous Creation Studio is a space for students, researchers, scholars, and community members to build trust, responsibility, and accountability with Indigenous Peoples and communities through Land and arts-based practices. Together, we reflect on how we as researchers navigate institutional waters, and what tools and strategies we're using to wade through the unfamiliar waters of our contemporary moment.

What projects in your space are you excited about these days?

Aimi Hamraie: One of the projects that my lab does is the Remote Access dance party. It's organized by a group of people spearheaded by Kevin Gotkin. We started out doing those parties in March 2020 as a way to show all the different disability culture protocols that can be entered into a digital space and made into ways of relating, having social time, and partying at a distance.

Various people who have organized the parties have tried doing a hybrid version, like moira williams, a disabled Indigenous artist who's part of the collective. They had this boat party on an accessible barge in New York City, with a digital component. Party planners are just constantly trying to figure out how far or how close we want to meet other people. How do we dance? How do we, like, let our bodies do what bodies want to do in a dance party space, after having them so isolated for a long time? How do we do this in person, and at a distance?

Maria Hupfield: We're taking on a digital archive as a curatorial project; one of the items is a wiigwaas jiimaan led by Kyla Judge, who brought together a group of Indigenous youth at the Georgian Bay Biosphere to make a traditional birchbark style canoe. She has developed all this protocol around it, Anishnaabemowin language, including handmade tools and seasonal care, and so we want to find a way to include these relations into our Indigenous Living Archive.

At the Indigenous Creation Studio, when I think about what art is I’m looking at this as trans-disciplinary because the term allows us to open it up holistically and move away from European or Western ideas of art as a painting on the wall. Art may be a performance or it could be a body but it never really includes the full scope of what some of these items are that come from Indigenous communities. So we strive to put our content back in right relations. In addition, we ask how art can be shown as living and a connected part of life today. Our efforts, much like my own practice, involve connecting artistic creations with movement and sound and wellness and doing this fully, not only to include the mind and the body, but also the spirit and the emotion as well.

In addition to the curated archive project we are looking at the campus as being in the middle of a medicine garden. The English translation strength of the earth garden—the word that we use Mashikiki Gitigan is the same word that you use for medicine and it's the same word you use for food and, well, all of that is considered strength of the earth. Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer and Leanne Simpson write about this, so it's known but we really want to apply it and understand and practice it here at UTM.

PROMPT 1: MOVING WITH CARE THROUGH INSTITUTIONAL WATERS

What relations are there between our labs/spaces and the institutional landscapes, which they are part of? Do these contrast with relations to other communities and other alliances?

AH: When I was a graduate student at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, my advisor Rosemary Garland-Thomson was very active in recruiting faculty all over the university into disability studies and convincing them that what they were doing was actually disability studies. I didn't really get why she was doing that until the university cut a bunch of departments one year out of nowhere. I talked to her shortly after those departmental cuts happened, and she was like, "this is why we develop relationships with people across the university; because they can't cut disability studies if it exists in every single department." It was really striking to me the technique of building relationships as a way of building a field and also creating power in an institution, as opposed to asking a Dean for money and space that can just be taken away tomorrow. I was also doing union organizing at the same time, and was having a lot of really frustrating run-ins with the university administration around that, and how they responded to forms of power that were legible to them.

When I was starting out at Vanderbilt [University], I was trying to figure out a version of that strategy. The campus was really inaccessible and the official institutional narrative was that the campus is 100% compliant with the law. And so I wanted to figure out, how do we get our campus to understand that that narrative is not true? So I created a lab and I called it that, because it’s a legible forum to all my scientist colleagues, and they understand a lab as a kind of social and academic gathering of people.

But what we do in the lab is of course very different than other forms of research. I intentionally never asked for space or official institutional recognition or anything like that, because then it could exist regardless of whether I have permission, and I could involve other people who do not have the same institutional forms of access that a lot of my students have. The Critical Design Lab is part of the university in the sense that I am part of Vanderbilt, but it's also floating above and beyond it, and exists in a lot of different cultural spaces within disability community.

MH: The pandemic changed everything. Whatever I thought was going to happen was absolutely not the case. One of the shifts I made for this year had to do with partnerships. I already was reaching out to try and build trust, connect with folks. I want to build community—or not even build it, but just try and get a sense of the landscape that's here and what's possible.

Also UofT was like, "Okay, this [lockdown] is lifting" and then suddenly it was like "Oh, we have [CAUT] censure and so now we can't host anyone anyway, even if we wanted to." I decided the way forward was to focus on these partnerships and then by handing the money over to organizations, they would host the events and that became a way to connect, to redistribute some of the resources that were available to me. How can the work that is happening in unconventional spaces support multiple levels, different types of careers, different types of livelihoods? That's something I've really hit up against when trying to connect Indigenous with Institutional models.

The other thing is people who specialize in Indigenous research; they're in high demand. So how do we not overtax our community? Aimi, you talked about how individualism is rewarded in academia. And I think that if we're wading through common waters, what I'm interested in is moving away from this idea of one—of a standard based in a singular male genius anchored in white supremacy and patriarchy—and moving towards something that is nonhierarchical, towards mutual support and alliances. I suppose the term that we often hear is “decolonial” or an “anti-colonial” model that opens up other ways of imagining a future that does not traumatize. So right off the hop at the Indigenous Creation Studio we developed a protocol handbook based on insights and guidance from the Digital Research Ethics Collaboratory led by Dr. Jas Rault and Dr. T.L. Cowan, Assistant Professors of Media Studies in the Department of Arts, Culture and Media (UTSC) and the Faculty of Information at the University of Toronto. They directed me to the work of Dr. Max Liboiron's CLEAR lab at Memorial University in Newfoundland, which applies feminist approaches to a research lab across multiple disciplines. There's a lot of models out there, but not necessarily in the visual arts.

Marim Adel, one of the students working as a Research Assistant at the ICS, has been working on an accessibility handbook as well, so we can include it into our practices as we bring guests onto the campus, including Elders. I think Zoom life really opened up a lot of thinking around Indigenous knowledge and access. There are certain Elders I would never have imagined being on Zoom giving teachings. Now people are able to attend all kinds of language classes and access other Knowledge Keepers. So how do we promote but still protect that knowledge in this digital sphere? How do we look at contracts as artists, so that we’re not just increasing amounts of unpaid labor?

ZW: Maria, this idea of promoting but still protecting—this is so important in the institutional era of equity, diversity, and inclusion (or EDI) that we're in right now. It gets so appropriative. Aimi, as you were saying, there's this pull for you or your work or your praxis to be made into the property of the university, even a crown jewel. This is in stark contrast from a key lesson in both disability and Indigenous work and worlding: the need to prioritize relations. This seems not to be happening in EDI, where people are operating in this extractive and consumptive mode, and then the question of relations just goes out the window. With the Research Kitchen I’m trying to be mindful of the time it takes to build those relations.

I'm also trying not to assume that I'm entitled to have any particular set of relations with any group of people, particularly outside the university. And actually, most of the work I’ve been doing to build the Kitchen thus far has been focused on building this space within the university. With the exception of a collaboration with Heritage Mississauga, the Kitchen hasn't branched out yet, because I feel like we're not there yet; I haven't built those relations yet. It's really important to be able to move slowly. This is certainly part of wading; moving slowly, not diving right in. I learned this from my previous position at Rice University, where I did dive in but it ended up being really wasteful. Wasteful of the resources I had access to, wasteful of my own energy and the energy of other people. I was building on a sense of enthusiasm that people had, rather than relations.

PROMPT 2: SHOW AND TELL

Can you share an artifact of your work that speaks to how your research space is being shaped by this particular historical moment?

ZW: What I have is a piece of paper from a very large notepad. It's got coloured lines making different quadrants, and writing in different colours showing different tasks, skills, and desires. It's from some delegating and brainstorming work that we were doing to organize an intensive month-long undergraduate research project. On our first day together, my co-facilitator Sophia Jaworski and I decided to take the students outside and to drag a whiteboard to a patch of woods on UTM campus where one of Dylan Miner's platforms is installed. I had assembled this giant bag of cushions and clipboards and markers and things, so we could work in the fresh air. And one of the things that happened was these students who had signed up to do an intensive research project found themselves sitting in the woods eating Persian herb omelettes and thinking about what they need to flourish.

The work on this piece of paper is from a day that the students decided—without prompting from me—that they didn't want to work in the kind of dark classroom we'd been assigned, and instead wanted to go sit on one of Dylan Miner's platforms out in a little patch of dandelions.

In the end, we had some terrific outputs but those outputs only emerged out of practices indebted both to feminist research praxis and to principles of disability justice. It was really wonderful and in some ways, concerns about COVID provided almost an alibi for these wacky practices: the idea of working outside made people slightly less uncomfortable than it would have otherwise. People were perhaps more ready to wade into new waters.

AH: I do have something, and I want to share a backstory. So, one of my touchstones for doing work that is out of sync with the institutional productivity demand is critical race theory, which interrupts the idea that the law is this objective fact. Derrick Bell, in his book Faces at the Bottom of the Well, has this chapter where he tells you that he’s in the woods typing on his laptop, and he’s writing a kind of boring didactic law review article, when all of a sudden this person who looks at first like he could be a white supremacist— they’re holding, like, a gun and walking around in the woods—comes up to him and starts talking to him. And Bell says, “I was doing this weird but beautiful thing, producing my article by sitting on a chair typing on this laptop,” (which was then new technology that enables this in the woods), “and now there’s this person who’s here and like, am I safe? What’s going on?” It turns out this person is part of some white anti-racist group, and they have a whole conversation about institutional racism. It’s kind of a parable, because critical race theory uses narratives and stories and fiction to make different academic arguments. But I think about that all the time, the striking image of somebody sitting in the woods and doing academic work in that setting, in recognition of their connection to that space and their sitedness, but also how it's the complete opposite of working in an academic office.

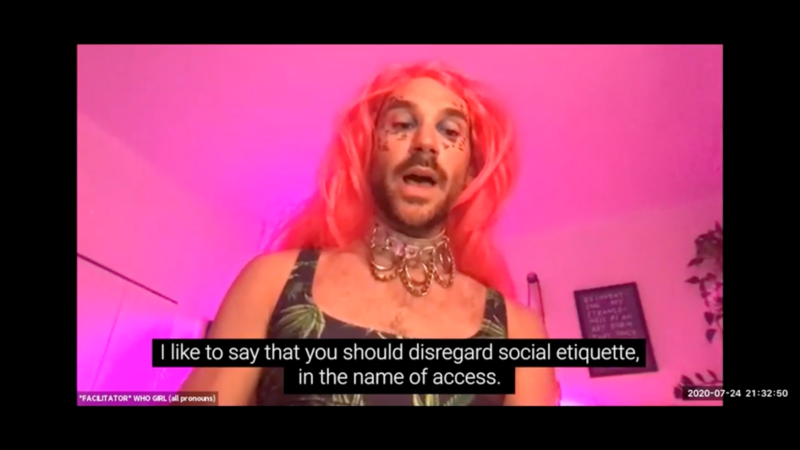

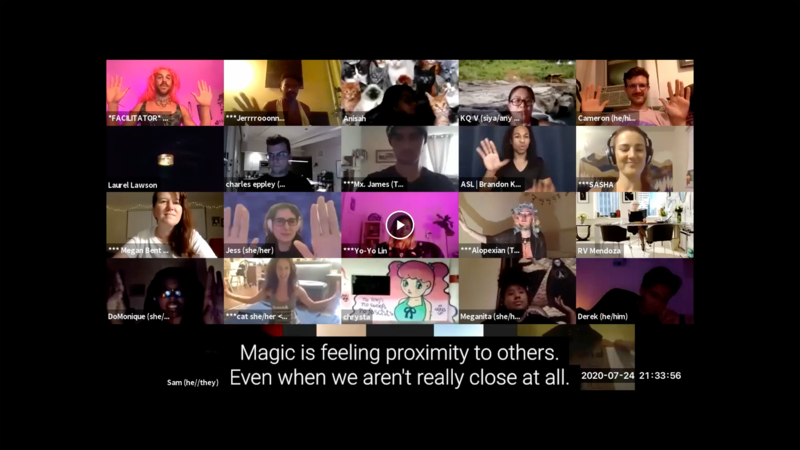

So this image is a screenshot from the second Remote Access party and it shows a grid of like twenty people like on Zoom. Some have pink light behind them. There's an ASL interpreter, and almost everyone is holding up their hands to the edge of the screen as if to touch the other people, at the direction of the facilitator and DJ. This is a moment of connection across time and space, with all these other people. The caption says, "magic is feeling proximity to others, even when we aren't really close at all."

This is one of the first instances of what Kevin Gotkin—who's the DJ in the upper left-hand corner wearing this green dress and a cool necklace and a pink wig and a beard—called "access magic," and the magic is the forming of connections and webs across space. In the early days of the pandemic, we all really needed that. There was a lot of healing and that sense of “I can't touch anybody, I haven't touched anybody for four months, but here I am touching people across the screen.” That became a blueprint for other forms of connection that could be created through these digital formats. So I wanted to share that and it’s a little bit like typing a law paper in the woods, because it's using this technology that I think was made for bankers to have meetings across time zones or something, but you know, having a crip dance party.

MH: I'm really curious about some of your archive strategies, Aimi. One of the things we're always trying to think through is what to include and how. For example, I talked about the jiimaan, but we also have another item in the archive titled "My Grandmother was Born on the Blueberry Patch," which is a little purse that's been beaded on hand-tanned leather. We've been able to document it with photogrammetry, so you can see it in the round. There's little bells on it and beautiful beadwork on both sides. When we talked to the maker, an artist named Caitlyn Bird, we asked what else we could include with it. One of the things that came up was the whole blueberry economy in the north.

Caitlyn interviewed their grandmother's sister—because their grandmother passed away and they didn't know their grandmother—so we could have those audio pieces in the archive as well. Then their grandmother's sister also passed away. So, we're navigating all these different ways to fully represent something like "My Grandmother was Born on the Blueberry Patch." How can we really realize it, locate it within family and geographically within land relations?

AH: What you're doing is so interesting because you're creating a material archive that has the stories of the material things, places, and people who are connected to them. It's a similar approach that we want to take for the Remote Access Archive. We're not just doing oral histories on their own. But sometimes the material is lost, and so it can only be described and recounted. For example, disabled people used telegrams to get in touch with each other across long distances, but they're only in someone's memory. Then, sometimes, you're able to find the actual object and digitize it in some way, or to find historical documentation of it somewhere, and include that.

I was talking to the disability historian Susan Burch. All her work is about institutions, and she had written about the institutionalization of Black men in the Jim Crow era and has a new book about the institutionalization of Indigenous people in North Dakota in what was called a “mental asylum.” She shared that one of the ways people connected outside of the institution was through quilting. There were messages sent back to families through quilts, and there was an equivalent practice with residential schools in that same area and time. So I'm trying to find out what those kinds of things are. I don't think those quilts exist anymore, but Burch had stories about them in her book.

Then there's this whole other history of the present part. How do we capture this ongoing history? There's so much that's happening around COVID, how do we capture that in real time? I've asked people to do oral histories about the present, and they're kind of confused because they say, “it's happening now, how could this be historical?” There are students at UCLA that have been doing sit-ins to demand remote learning for months, and they were like, “Here's our protest signs but we're not ready to talk about this yet. We will do an oral history in a year, maybe, but right now we're just too in the weeds of what's happening to even be able to reflect on it and know what's important to share.” I'm sure there will be interesting things once they start talking, like with telemedicine and telehealth. There's a lot to navigate around how you share your medical encounters and what needs to get redacted or what's community information versus information that can go to public archives.

MH: Thank you—you just shifted something in me. It feels like, “Of course!” Taking that extra leap from object to voice is necessary. We really want to hear a voice with each of these objects. The speaker’s positionality can connect us back to truth and context; context is everything. In history museums, they historically didn’t even bother to know who the maker is—who collected it often is all that's important.

I'm going to talk about something I use a lot in my own practice. You may have seen these before; it is just a little Jingle. It starts as a circle cut out of tin that gets hand-curled to make a cone. It looks a lot like a bell but it doesn't have a hammer inside it so they need each other to make sound. I think this is a really nice way of thinking about individual versus collective models. The other thing about the Jingle is that they are worn on a Jingle dress which is a healing dress, and a very recent dance form. It shows cultural innovation and survival and something that we have learned during the pandemic was that this form of dance started during another pandemic [the 1918 influenza pandemic]—that's when the Jingle dress surfaced.

Thinking about the Jingle as a sound; how do you embody sound? This changes your movement but also this idea of sound and thinking about the word "truth." Jim Dumont talks about truth, the word debwe. The ending of the word “we” or “we-we” (pronounced way-way), which has to do with sound, so listening to your truth. A Jingle, and the Jingle dress, the sound of it, which is also like a shaker or shesehkwan also recalls water. All of these things are connected. The healing and the wellness of water and the sound of the water in the womb: that takes you back to creation. So with these ideas of truth and embodying knowledge and living a truth in mind, I've been thinking about how to listen, how to listen deeply. That takes me towards future work that has to do with language and voice and speaking. Not just embodying it but also the responsibilities that come with speaking when you're based in an oral tradition like I am as an Anishinaabe person. When you're putting words out in the world, what those mean, living it versus just writing it down. These are other methodologies, that we can look to, that have always been there, but haven't been visible or active in the same kind of way. I agree that we're in a moment where there's a lot of experiential learning that I’ve been called upon for at UofT. These little jingles are part of that work I’ve been doing.

See Connections ⤴

Maria Hupfield (she/her) is a transdisciplinary maker working at the intersection of performance art, design and sculpture. She is the 2022 ArtworxTO Artist in Residence with solo projects at Patel Brown, Toronto, and Nuit Blanche fall 2022. Hupfield is an Assistant Professor and Canadian Research Chair, cross-appointed to the Departments of Visual Studies and English and Drama at UTM, with a graduate appointment in the Daniels Faculty. Hupfield is lead artist at the Indigenous Creation Studio. She is Marten Clan and an off-rez member of the Anishinaabe Nation belonging to Wasauksing First Nation.

See Connections ⤴

Zoë H Wool is Assistant Professor in Anthropology at the University of Toronto Mississauga, where she teaches about toxicity, disability, and the tyranny of normativity. She is author of After War: The Weight of Life at Walter Reed, co-founder of Project Pleasantville, a community-engaged archive of Black leadership and environmental racism, and is Director of the TWIG Research Kitchen, a convivial feminist space for work on toxicity, waste, and infrastructure.

See Connections ⤴