- 08.0Cover

- 08.1Block Out the SunStephanie Syjuco

- 08.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 08.3Racial Justice in the Distributed WebTaeyoon Choi

- 08.4Coded Bias: Race, Technology, and AlgorithmsMeredith Broussard, Beth Coleman, Shalini Kantayya

- 08.5Feminist Data Manifest-NoFeminist Data Manifest-No

- 08.6Artists-In-PresidentsConstance Hockaday

- 08.7The Great SilenceTed Chiang

- 08.8Elements of Technology CriticismMike Pepi

- 08.9JunkTommy Pico

- 08.10HOW ARE WE:

A SMART CONTRACTEmily Mast & Yehuda Duenyas

- 08.11Forecasted FutureD.T. Cochrane

- 08.12They are. We are. I am.Tiara Roxanne

- 08.13Glossary

They are. We are. I am.

- Tiara Roxanne

They are. We are. I am. is a data visualization project I created with Trinity Square Video (TSV) in Toronto during the first COVID-19 lockdown.

On March 17, 2020, I bought a one-way ticket to New York City from Berlin. There were only American passport holders on my flight, and nearly everyone had their own row throughout the entire United Airlines airbus. When we landed, they announced that we were one of the last flights allowed to land on US territory from Germany without restrictions. Some hugged, others dropped their shoulders and looked out with worry-lined eyes. “What will we do now?” a flight attendant asked as we waited to leave the plane, “I can’t pay rent.” As dread saturated the humid air, an ocean of uncertainty welcomed us in New York.

I had originally planned to fly into Toronto, the home of TSV, a gallery that supports artistic work that unsettles the technological norm. That changed when Canada stopped accepting flights from non-Canadian citizens. Emily Fitzpatrick, the gallery’s Artistic Director, and I had been planning my exhibition for nearly a year. Between our video calls across Berlin–Toronto borders, Emily had booked me a tour that consisted of a lecture for SUNY Buffalo’s PLASMA series; a performance at Squeaky Wheel Film & Media Center in Buffalo and talk with critic, writer, and curator Nora Kahn; and a performance and talk with artist and writer Ella Schoefer-Wulf at the Images Festival, presented alongside my exhibition They Are. We Are. I am. at TSV. Altogether the tour would take up most of April 2020—but the beginning of the pandemic in early March signalled a startling halt to these plans. My lease was ending in Berlin and the question of borders closing led my ancestral heart into panic. I felt an urgency to be on the land from which my ancestors breathe—from which I am born. I needed to be with la tierra, mi corazón, so I bought the first available one-way to New York and moved to Queens for an uncertain amount of time. Once I landed, Emily and I, along with the team at LANE Digital,11LANE Digital is Aljumaine Gayle, E.L. Guerrero, Ladan Siad, and Nabil Vega. LANE builds human-centred, community-focused concepts that lead to a more just and equitable future. Their interdisciplinary studio is about unearthing and unsettling—we work together to conceptualize new ways of listening, seeing, feeling, and understanding social issues through design. Their work is rooted in black, queer, anti-capitalist, diasporic, feminist methodology, and pedagogy. scrambled to move my exhibition, talks, and performances online in a matter of days, which manifested in my data visualization project at theyareweareiam.com.

In moving this work online, a major consideration was to translate embodied experiences of different forms of data colonialism—from spatial experience in the gallery to digital experience. For example, plans for the exhibition required visitors to actively encounter data mining practices by completing a questionnaire and visualization of their data If they did not complete this first step, they would not be permitted to experience the rest of the artwork; entry would not be allowed. This is an embodied marking of (de)colonial subversion.

Because decolonization is not possible due to the implication that it requires the settler to give land back to Indigenous peoples, I am instead interested in active forms of acknowledgment that lean into the more embodied or experiential—or, toward gestures of decolonization. As my work engages with the impossibility of decolonization, I ask participants to encounter the embodied gesture by actively acknowledging the damage of data colonialism. What then becomes necessary from all visitors to the work, regardless of their background, is the recognition of the ongoing violences and injustices against Indigenous peoples that drive the continuation of settler colonialism. In its move from gallery exhibition to digital space, this project enacts and experiments with different modes of encounter with data colonialism, asking:

How do we encounter embodied experiences in digital space? How does the body become data? What knowledges and memories inform our movement through digital space? What kinds of collective experience and encounter are possible through data visualization? What gestures of decolonization and togetherness are possible in the digital (without appropriating Indigenous tradition or ritual), and what gestures of colonization do our existing digital systems reinforce?

The work opens with this statement:

“Aztecas del norte, mojados, Indigenous peoples, First Nations People, mestizos, Redskins, American Indians, Mexican Indians, Native Americans, Natives, savages, minorities, at risk peoples or asterisks peoples are some names or codes the Indigenous body is subjected to using settler colonialist language. The settler names the Indigenous person which codifies and marginalizes. Not only does artificial intelligence learn from these colonial pre-existing biases, it also re-inscribes the notion that Indigenous peoples no longer are but were.”

We are still here. But Indigenous peoples’ data is regularly misconstrued and often not included in larger and important datasets, ultimately reproducing settler-colonial erasure. This is data colonialism: the collision of practices of historical colonization with the abstract quantification methods of computing.

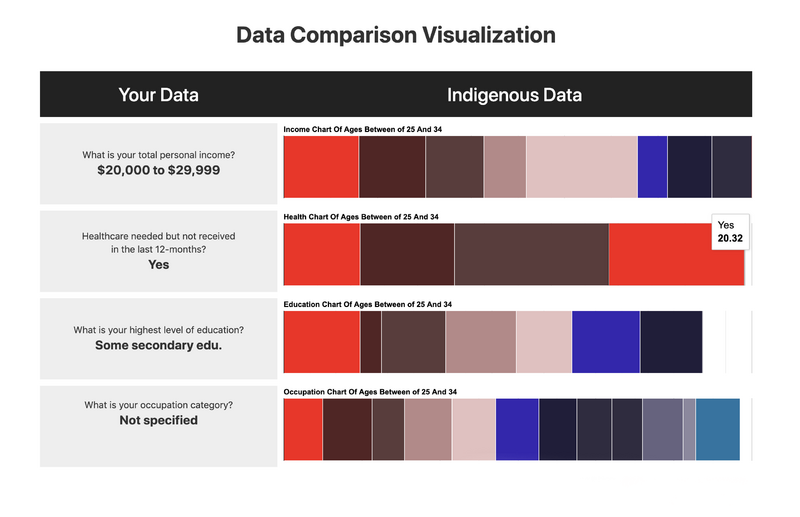

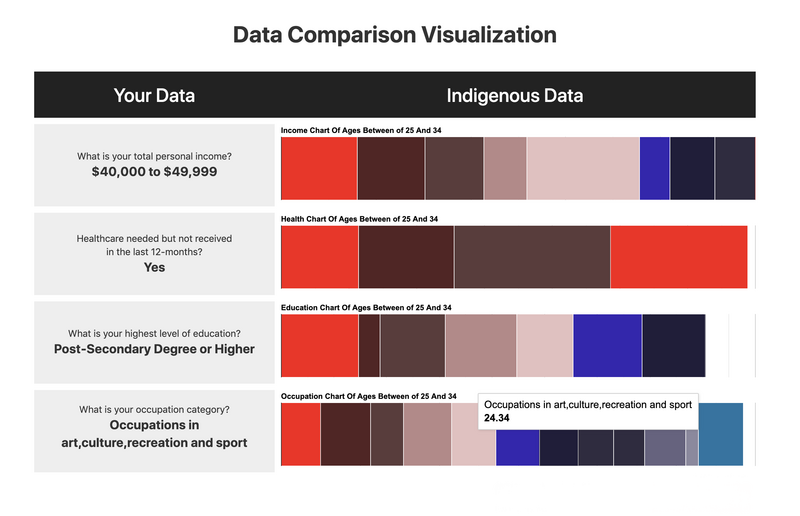

They are. We are. I am. prompts the visitor to offer their own data points, which are later compared to data points pulled from the Aboriginal People Survey (APS) for First Nations people living off-reserve, Métis, and Inuit living in Canada. The team and I chose to request data in the following areas: age, education level, occupation, and health access. These categories of data display the most disparate inconsistencies between the visitor and the extracted APS data. It is important to note that the visitor here is used to describe the average patron of contemporary art. However, we acknowledge that there would be folks of different ages and backgrounds and wanted to provide an experience with the most variety of output. With that said, for Indigenous peoples exploring the data visualization, it was geared toward solidarity and resource sharing. It is important not to collapse the different identities of patrons visiting the work. We wanted to display dissonance within the data. The most obvious data point to exhibit disproportion was health care, followed by total personal income, and level of degree achieved.

A 25–34 year old visitor’s data is arranged along the left side of this image. Indigenous data for the same age range from the APS survey is shown in the varied colour blocks to the right. Upon mouseover, the percentage each colour block represents is provided. In the healthcare line, a large number of individuals have answered “yes” to “healthcare needed but not received,” followed by “not stated,” and “do not know.” See figure below. Thereafter, this is data colonialism in action. When an Indigenous person either does not have access to resources or is not represented within the dataset, they are erased from the state funding, healthcare or otherwise.

When Indigenous peoples are not included in datasets, they do not exist. This means that they will not receive aid or assistance if needed. This is settler colonialism set within the framework of data mining practices. The Indigenous person’s identity is extracted and erased.

Intervening phrases that draw from my larger work regarding decolonization, intergenerational trauma, and AI bias surround the “Data Comparison Visualization” page. I had hoped to have participants record themselves speaking these lines, enacting an embodied form of acknowledgment. A decolonial gesture. Without the recording, the participant would not have been permitted into the larger exhibition space. But the recorded audio provided by the participants would also have been integrated into a sonic (de)colonial cacophony. In this way, audio could stand in as a form of (un)seenness, asking the participant what it sounds like to be colonized, marginalized, or lost in a dataset. I continue to ask: how can we work in solidarity while also acknowledging and grieving the active erasures that data colonialism carries out? How can the digital, the tactile, and the auditory create alternative ways to occupy and move through systems that are designed on the basis of extraction? What kinds of physical and digital spaces can reorient toward recovery and refusal?

The exhibition—and its spatial, auditory, and embodied arrangements—is still a fantasy I wish to bring into reality post-COVID-19. For now, theyareweareiam.com serves as a space to mediate and acknowledge data colonialism for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples within the Canadian borders (and Indigenous peoples more generally). I hope to extend this space beyond the material and digital borders settler colonialism has forcefully brought upon us Indigenous peoples.

As I write from a cozy corner of Neukölln, Berlin, the sun begins to set at four pm and winter slowly settles its cold shadow in the midst of the second wave of COVID-19. There is a calm in the cold, in the distance between bodies. Surrounded by upward-facing leaves, brightly coloured and open-ended palms that welcome the many feet that walk the Ufer (with a loved one, with a friend), the angst that once surrounded my feeling of uncertainty in New York is now transformed into a soothing Berlin backdrop. A surrender in the blackbird winter. We learn to gather differently now. To care with grace. An undoing of panic. The sky is kind today.

See Connections ⤴