- 03.0Cover

- 03.1IBC (Indian Brand Corporation): Dystopic AutonomyJoseph Tisiga

- 03.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 03.3Carrying CapacityMarina Roy

- 03.4Open Letter to the Federal GovernmentW.R. Peltier, D.W. Schindler, John P. Smol, David Suzuki

- 03.5Claiming Bad KinAlexis Shotwell

- 03.6A Brief History of FeelingJacquelyn Ross

- 03.7Energy-Bearing MediaJeff Diamanti

- 03.8Figures 1928, Airline routes and distancesMalala Andrialavidrazana

- 03.9What is Growth?D.T. Cochrane

- 03.10This, Too, Will ContaminateJoy Xiang

- 03.11The Need for Urban Climate JusticeSara Hughes

- 03.12The role of municipalities in changing behaviours

The Climate Change Project, City of Mississauga

- 03.13A PEOPLE'S ARCHIVE OF SINKING AND MELTING: NUNAVUTAmy Balkin

- 03.14Local Useful Knowledge: Resources, Research, Initiatives

- 03.15Glossary

Energy-Bearing Media

- Jeff Diamanti

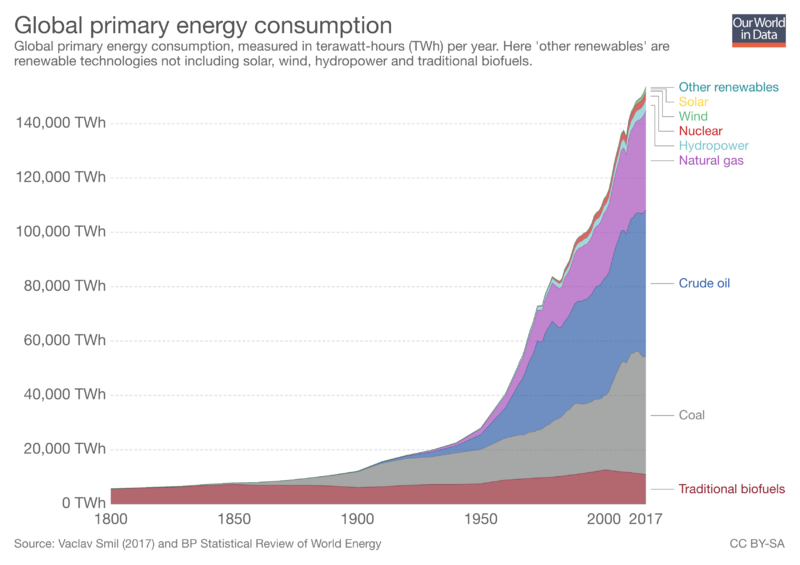

The typical story of long-term growth posits the steam engine as the predecessor to the microprocessor, and the information economy as a stage of development towards which industrial economies tend. Why then does it look like our energy problems will last well into this century? According to recent estimates from the International Energy Agency, the world will need upwards of 30 percent more energy in 2030 than in 2017 in order to maintain positive, global growth.11International Energy Agency, “World Energy Outlook 2017: Executive Summary,” http://www.reuters.com/article/us-eia-global-demand-idUSN2719528620090527. Compare this to the surge in energy from fossil fuels that underwrites the story of twentieth-century modernization. Already in heavy use in the first half of the century, by 1950 oil would become the dominant source—both qualitatively and quantitatively—of advanced industrial development, but would somewhat paradoxically generate the conditions for a parallel dependence on coal and natural gas to keep up with the electrical needs of an oil-based economy. The cultural and economic sequence named as the “postindustrial” is thus underwritten by a proliferation, rather than retreat from, fossil fuels. My argument here is that this increase in energy-bearing media renders the practical and tangible force of fossil fuels both ready to hand and out of sight, even as the cultural imaginary of cloud computing turns information and communications technologies into a kind of dispositif of environmental futurity. As well, this dependence on fossil fuels is a paradox because it exposes the material entanglement of deindustrialization with territories of extraction and the historicity of hydrocarbons, in turn focalizing what Jonathan Sterne calls the techné of communication into a mode of feeling out (and therefore repurposing) energy-bearing media.22Jonathan Sterne, “Communication as Techné,” in Communication as… Perspectives on Theory, eds. Gregory J. Shepherd, Jeffrey St. John, and Ted Striphas (London: Sage Publications, 2006), 93.

Let me put this another way: In Robert Ayres groundbreaking 2013 analysis, energy explains one of the most difficult puzzles associated with economic growth after 1945. Upwards of twelve percent of growth in the twentieth century remains unexplained so long as energy is considered an independent variable in economic growth. Neutral on the category of energy, the math simply won’t add up. Which is another way of saying that the macroeconomic metrics of capital deepening (the increasing investment that typifies every sector of the economy over time to maintain growth) and labour productivity do not account for the economy’s dependence on steadily drawing more and more power from natural sources—which we might term energy deepening. When Ayres internalized energy in their measures of growth, continuous global growth became fully explained, despite falling labour inputs (due mainly to automation) at the macroeconomic scale.33Robert Ayres et al., “The Underestimated Contribution of Energy to Economic Growth,” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 27 (2013): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2013.07.004.

But adding energy back into the quantitative map of economic growth does more than solve a math problem. It also suggests a qualitative structure to the energetic character of capitalism’s path dependency following the introduction of fossil fuels into the production process. The real insight offered by Ayres’s demonstration was that continuing economic growth under conditions of capitalism depend upon a logic of productivity first introduced to the world during the industrial revolution—that, in short, this introduction of fossil fuels into the dialectic of labour and capital bound future rates to a similar structure. It was hard for most economists to think energy back into the picture because it was all too often figured as a material input (a cost that would appear under the heading “capital”) rather than a force structuring growth more generally.

To the extent that this path dependency, or what Harvard economist Dale Jorgenson calls “the role of energy in productivity growth,” is about overcoming limits to profitability by expanding and intensifying the flow of energy across all sectors of the economy, we can also point to the recursive relay between natural, social, and economic environments: the settings, in other words, through which energy inter-implicates different environments.44“The data support the hypothesis that electrification and productivity growth are interrelated. Somewhat surprisingly, the data also show that the utilization of nonelectrical energy and productivity growth are even more strongly interrelated.” Dale Jorgenson, “The Role of Energy in Productivity Growth,“ The American Economic Review 74, no. 2 (May 1984): 29.The relay will be an evolving range of technologies and techniques that call attention to energy—media that render energy from coal, oil, and natural gas into work, information, and environment.

Hence, Ayres and Jorgenson see in twentieth-century fossil fuels the shape of a solution to a problem of econometric representation, which in turn helps them put energy at the heart of economic growth. Certainly this moves past the conventional understanding of fossil fuels as mere input into a system otherwise conceived as independent from them. Implicit in the concept of energy deepening, though, are two contradictions: one, that fossil fuels, among other things, help capital shed labour—I’ll explain in a moment why increased computational capacity extends this problem; and two, that more energy will often appear like a solution to the contradictions caused by energy deepening. Unlike other energy transitions in human history, the system built around fossil fuels generates a loop where, to use the phrasing from historians M. Jean-Claude Debeir, Jean-Paul Deléage, and Daniel Hémery, “the solution to its energy problems” is sought “almost exclusively in deepening the logic of producing energy from these fuels."55M. Jean-Claude Debeir, Jean-Paul Deléage, and Daniel Hémery, In the Servitude of Power (London: ZED Books, 1991), 12–13.The energy system built around the twentieth-century intensification of fossil fuel extraction, in other words, engenders an epistemological impasse where solutions to social contradictions of a world saturated in oil are sought in the technological increase of the energy available from fossil fuels.

Examples of ways around this impasse include the tendency towards building larger cities and enhancing the infrastructure that connects them to combat slow economic growth; the search for fuel reserves that bring the “energy return on energy investment” (EROEI) closer and closer to parity; using a carbon tax to finance (or purchase) a transnational pipeline; greening the business environment by moving the corporate office onto the cloud; and becoming more and more agriculturally dependent on petrochemical fertilizers, the efficiency of which makes any switch to organic fertilizers demographically homicidal. Once pegged to a certain set of soft and hard infrastructures of growth, fossil fuels generate something of a feedback loop that complicates (if not precludes) any future energy transition.

Implicit too in both Ayres and Jorgenson’s attempts to refigure energy as a structuring force of economic growth (as opposed to a mere internal variable to be counted on the balance sheet of capital) is that energy surges through all manner of technologies, social relations, and historical tendencies in ways that are difficult to quantify. It is this expanded force of energy over the shape and tendencies of the present that requires a media theory of energy, since fossil fuels do not hover in some ethereal void above history—though their emissions certainly have a way of hovering—but are rather distributed into the world through concrete technologies, practices, and habits. Both as an environment of media, and a mediation of the biophysical environment, what fossil-fueled path dependency amidst deindustrialization requires is an account then of “energy-bearing media.”

Implicit in this schematization of fossil fuels is the idea that the environment of media, to use Marshall McLuhan’s phrasing, is a measure of that medium’s recursive relationship to the energy system that makes it go. Yet to the extent that it’s in the capacity of energy to organize an environment that we’ll see its impact on cultural history, it’s also true that we’ll hardly ever see it at the level of content. When we do—say in an encounter with an oil rig or a coal shaft—we are not necessarily in on some secret about how energy works across media. This is why thinking energy-bearing media means rethinking the setting of different media in relation to the material and social history of energy deepening. McLuhan’s axiom is that “each new age creates an environment whose content is the preceding age,” and that while you can see content (belatedly), you cannot see environment. With energy-bearing media, the axis begins to look reversed: the setting generated by fossil fuels contains a history in more ways than one—millennia of compact matter, centuries of colonial violence, and decades of technological development—but its orientation is towards the future as growth and development, as well as global warming. Indeed, energy does funny things to media.

On the other end of the postindustrial sequence that begins in the 1960s, the media system we call the (data storage) cloud, and the world of information and communication technologies (ICTs) that rely on it, form the infrastructure of global culture and commerce. In the recent turn to materiality in media, communications, and environmental studies, researchers and activists have found new ways to see the connections between electronic clouds and climate change. The connection here between the infrastructure of cloud-based computing and deindustrialized labour is the energy content modulating both. For instance, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce, per-worker consumption of electricity increased 232 percent between 1950 and 1984.66Bernard C. Beaudreau, Making Markets and Making Money (London: iUniverse, 2004), 100. Per worker, the postindustrial is far more energy intensive than the industrial, not just because it relies on a global logistics and supply chain that has been overwhelmingly dependent on cheap fossil fuels, but because the very environment of postindustrial production and consumption is lit up like a Clark Griswald Christmas display. Cloud-based computing is enormously resource-intensive, from the ground up through assembly, distribution, maintenance, and operation, yet amidst the computational sublime of the cloud is the global division of labour as such: from the hyperexploitation of miners and service workers in extractive industries to the hyperattention required of postindustrial work. Every four years the cloud’s energy requirements double, and with it the lion’s share of postindustrial profit: In Q4 2015, Amazon Web Services generated 7.88B USD in revenue, up 69 percent from the same quarter the year before, and its hardware is only one collection in a rapidly expanding sea of data-storage providers, such as EMC (now Dell), IBM, Microsoft Azure, and quickly rising Google.77Louis Columbus, “Roundup Of Cloud Computing Forecasts And Market Estimates, 2016,” Forbes, 13 March 2016, http://www.forbes.com/sites/louiscolumbus/2016/03/13/roundup-of-cloud-computing-forecasts-and-market-estimates-2016/#3cc4e5c74b07.

Today the ubiquity of media—which as we just saw was a result of, as well as the condition for, the ubiquity of an industrialized energy system—is starting to refigure the forms and flows of labour that keep profit rates competitive. One can plot, in other words, a loop of labour up through what Benjamin Bratton calls “The Stack”: the layered reality of hard and soft infrastructures that connects earth, cloud, city, address, interface, and user.88Benjamin Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016). Figured vertically or horizontally—from subsoil up to the atmospheric waves, or from the gentrified core of the new economy across to the special economic zones of the global economy—the layers that make up the stack pull together the social and environmental contradictions of energy-bearing media. Industrial work generated one set of experiences in relation to the machine and the factory, and these persist of course at certain levels of the stack. Meanwhile, postindustrial work means something fundamentally different. But what precisely does this new environment of cloud-based commerce mean for the experience of work? Using Thomas Whalen’s 2000 term “cognisphere” to describe this new work environment, N. Katherine Hayles emphasizes that “human awareness comprises the tip of a huge pyramid of data flows, most of which occur between machines.”99N. Katherine Hayles, “Unfinished Work: From Cyborg to Cognisphere,” Theory Culture Society 23, no. 7–8 (2006): 161. This parceling out of human input into a flow of information and energy that, at scale, operates independently of any one user or group of users in many ways literalizes the theory of a decentered subject foretold by leading postmodernist theorists, such as Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, and Judith Butler. As a feature of cloud-based computation and commerce, however, the experience of decentered subjectivity is entirely bound up with the global infrastructure of fossil fuels—in other words, if I may be so bold, experience of the cloud is as close to an experience of our global energy system as filling up your car with a tank of gas.

Why then is it so hard to see fossil fuels in our daily habits and habitats, and to see labour in the computational processes and energy intensity of postindustrial society? The ubiquity of polymers in consumer products and electronic components is one side of the more general shape-giving quality of oil, which extends invisibly across the habits and attachments of modern petrocultures. Oil’s plasticity is thus both the quality that sets it free to reign over the material world—to get lodged in it and to change its landscape indelibly—and the one that alters the world of social relations by shaping and accelerating a kind of materiality appropriate to global citizenship. This uniquely historical quality of energy is impossible to grasp without a long view of energy-bearing media that locates energy flows between media and environment.

See Connections ⤴