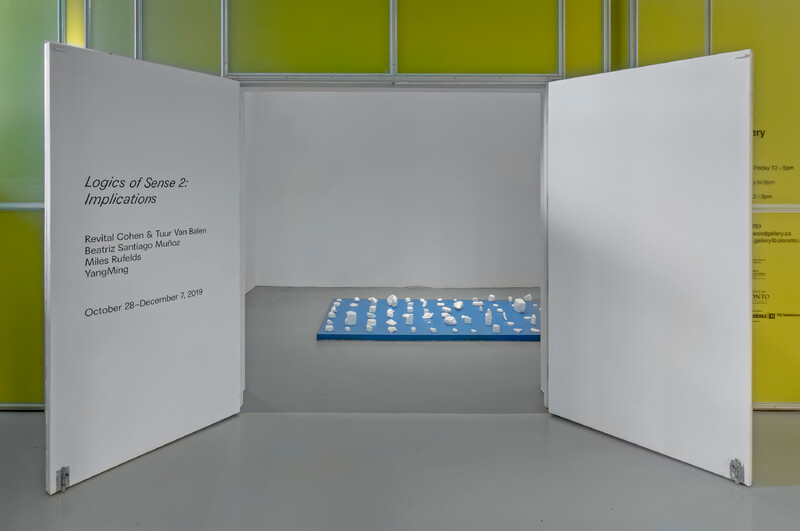

The Weather at Olympus

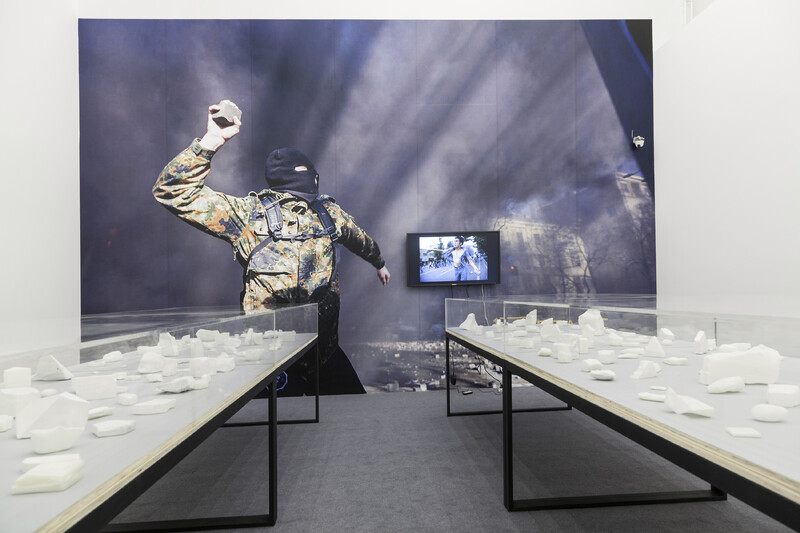

Inkjet print on vinyl; HD video with footage from the Internet; 3D scanned and printed objects, ABS photosensitive resin, variable sizes.

It’s useless to wait for a breakthrough, for the revolution, the nuclear apocalypse, or a social movement. To go on waiting is madness. The catastrophe is not coming, it is here. We are already situated within the collapse of a civilization. It is within this reality that we must choose sides.

—The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection

Street demonstrations triggered by various political upheavals around the world have led to numerous conflicts between protesters and police. Against an ever-increasing militarized response by so-called “authorities,” the weapons used by demonstrators in these confrontations are most frequently the ubiquitous debris of the urban landscape: cobble stones, broken bricks, and concrete fragments from the dilapidated streets, buildings, and monuments of contemporary cityscapes. This rudimentary detritus, in the hands of a public under attack in asymmetrical urban conflict, become objectiles for self-defence and contestation.

The term stone pelter—referring to “people who throw stones”—has become a part of the current vernacular to describe street protestors who appropriate these geological ephemera during urban demonstrations, protests, and riots, and through their energetic release, convert them into new weapons. Can these sites of uneven, uncivil conflict therefore be described as Stone Wars? If so, although the Stone Wars do not cause excessive casualties, they nevertheless drain opponents’ combative power, making it more difficult for them to maintain forms of repressive control.

Reflecting on political resistance and upheaval through these moments of stone warfare, YangMing uses 3D scanning techniques to reconstruct models from photos and videos of protest objectiles found on the internet, and then renders them in vivid sculptural material to reproduce the form of found weapons with 3D printing technology. The display of this array of re-captured protest ephemera conjures an oblique sense of the built environment, shifting attention to the mundane debris of the city as a way of reconsidering the affordances of urban inhabitation and militant resistance

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are open. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.