The Interval and the Instant

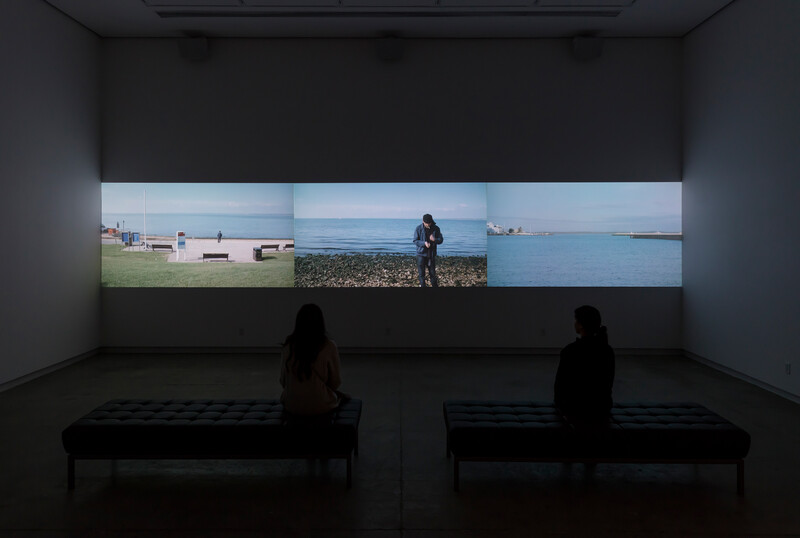

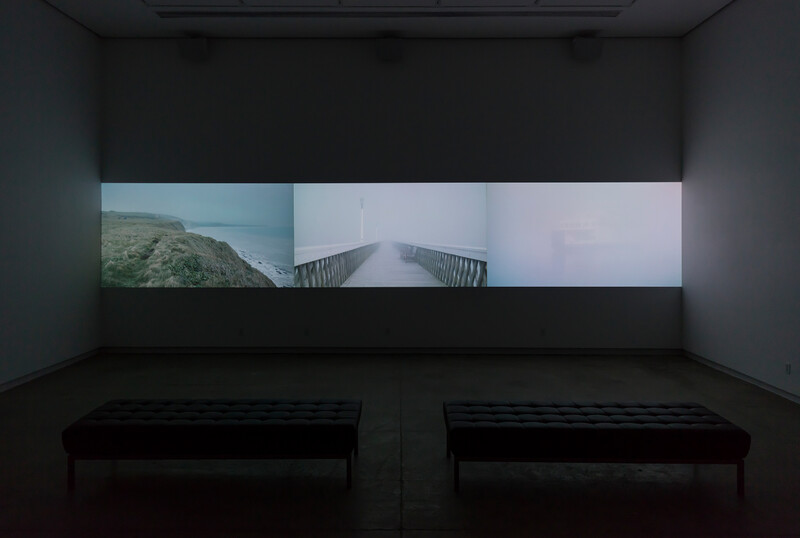

3-channel HD video installation, mono audio across three channels.

49:49, loop.

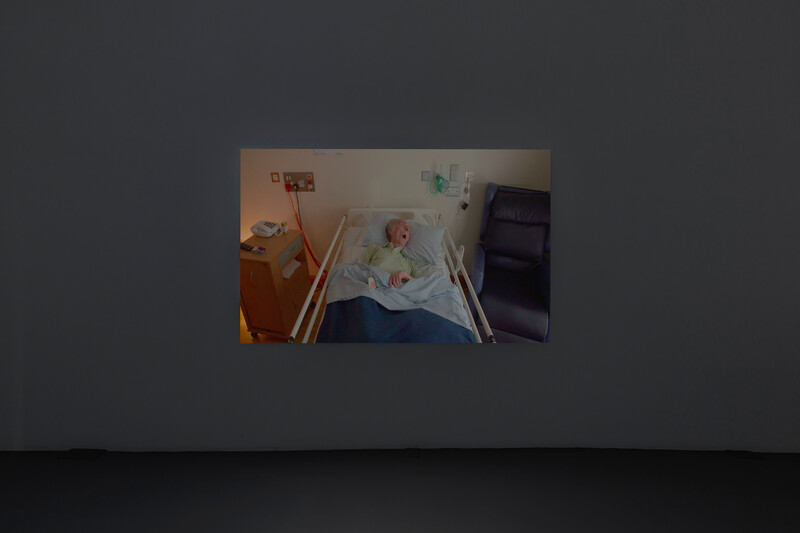

An intimate and patient encounter with the end of life in the context of palliative care, The Interval and the Instant is a multiscreen video installation that reworks footage from Eastwood’s feature-length film, Island (2017), a sustained engagement with four individuals navigating terminal diagnoses in a hospice on the Isle of Wight in England. Filmed over twelve months, Island is a life-affirming reflection on dying, portraying the transition away from active personhood and observing the last days of life and the moment of death. Based on extraordinary access to intensely private events, Island shows diagnosis, treatment, the progression of illness, and death—trialling, in the process, an ethics of looking at dying. Long takes and interwoven sequences document the temporal interval of terminal illness, following subjects from home to hospital to hospice, and the instant of death. Involving multiple screens and video loops of varying lengths, The Interval and the Instant’s centrepiece is a fifty-minute triptych, each screen witnessing one hospice patient—Alan, Jamie, or Roy—and working with extended duration. “Death,” says Eastwood, “takes its own time.”

The Interval and the Instant counters contemporary western culture’s tendency to partition dying and death, to regard mortality with anxiety, and to abstract death in metaphoric representations. On the deficit of moving images of death, Eastwood says: “If the person with terminal illness is denied a certain kind of participation in our culture, denied a certain kind of image, then denying that person an image is surely also contributing to how they are repressed in our culture.” While the subject remains stubbornly taboo, The Interval and the Instant shows dying to be natural and everyday—but also unspeakable and strange. Among the insights that have stayed with Eastwood after filming is, he remarks, a sense of how beautiful a good death can be: when care is really attentive, pain is managed, when somebody has lived a long life, and what you see is the gentle running out of a life—the end of breaths... I found it very empowering. It had a beauty. It had an unspeakable quality, and I am very fortunate to have been invited to see that. And I found it strangely uplifting."

The Interval and the Instant’s image of dying is generated in the institutional milieu of hospice care and, as such, its conditions of possibility include the care work performed by nurses and other palliative care professionals. Yet, says Eastwood, “I was halfway through one year of filming when I realized that I had no images of care. Whenever I produced my camera, the nurses would vacate the frame. We had a meeting with the nurses and said, ‘Listen, we are giving an inaccurate representation. If you see what I’m filming, it looks as though these people are abandoned.’ That produced a powerful shift in the nurses’ attitudes. They understood that it was important to act against their default behaviour. They had to allow themselves to be visible.” Eastwood’s project reveals the distinctiveness of the bond between nurse and patient in hospice care, with “the carer being witness to events, experiences, and expressions that wider society (or, at times, family and friends) do not see, and making representations (medical, corporeal, holistic) of the person cared for and their symptoms.” Eastwood’s work further evokes affinities between carer and artist: “In a situation like the making of this film, the artist is something of a stranger, or an interrupter. The filmmaker arrives for a limited time into the centre of a life, yet is granted uncommon relationships and access, because of a newness and strangeness. For me, one of the exciting things that filmmaking can do is produce new behaviour, for both filmmaker and subject. Talking with nurses, I realized they have similarly uncommon relationships with patients. Often their patients show parts of their personalities or reveal intimacies and private thoughts that they don’t share with their families. Nurses are also physically proximate to patients, so they know every aspect of them. This creates a window, almost a liberating opportunity, for the development of new relationships that don’t have to conform to patterns and histories.”

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently open. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm, Wednesdays until 8pm.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.