Wages For Facebook draws on the 1970s feminist campaign Wages For Housework to think through the relationships of capitalism, class, and affective labour at stake within social media today. Wages For Housework demanded that the state pay women for their unwaged housework and care-giving, as the market economy was built upon massive amounts of this unacknowledged work—and its labourers could be seen to constitute a huge working class. Wages for Housework built upon anticolonial discourse to extend the analysis of unwaged labour from the factory to the home. Along these lines, Wages For Facebook attempts to extend the discussion of unwaged labour to new forms of value creation and exploitation online. The launch of a manifesto website, wagesforfacebook.com, in January 2014 clearly hit a collective nerve. Since then the project has been debated widely via social media, at universities, and in the press, setting off a crucial public conversation about workers’ rights and the very nature of labour, as well as the politics of its refusal, in our digital age. [E]very social relation is subsumed under capital and the distinction between society and factory collapses, so that society becomes a factory and social relations directly become relations of production.1

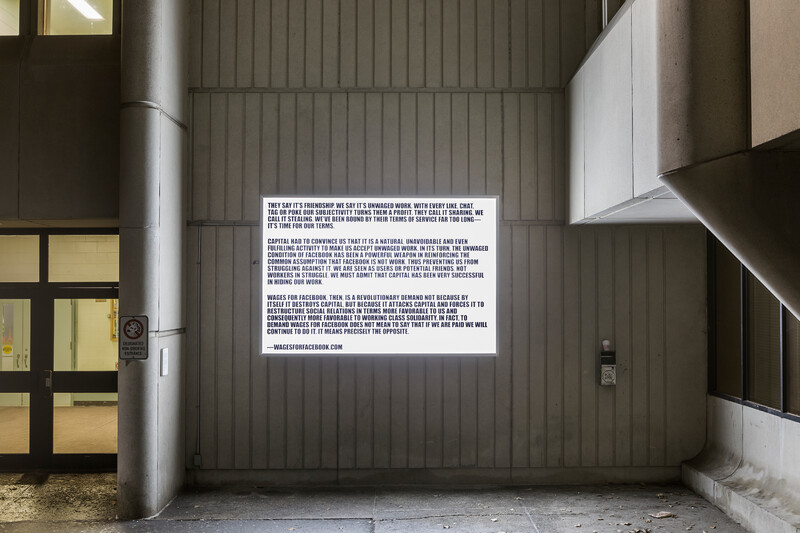

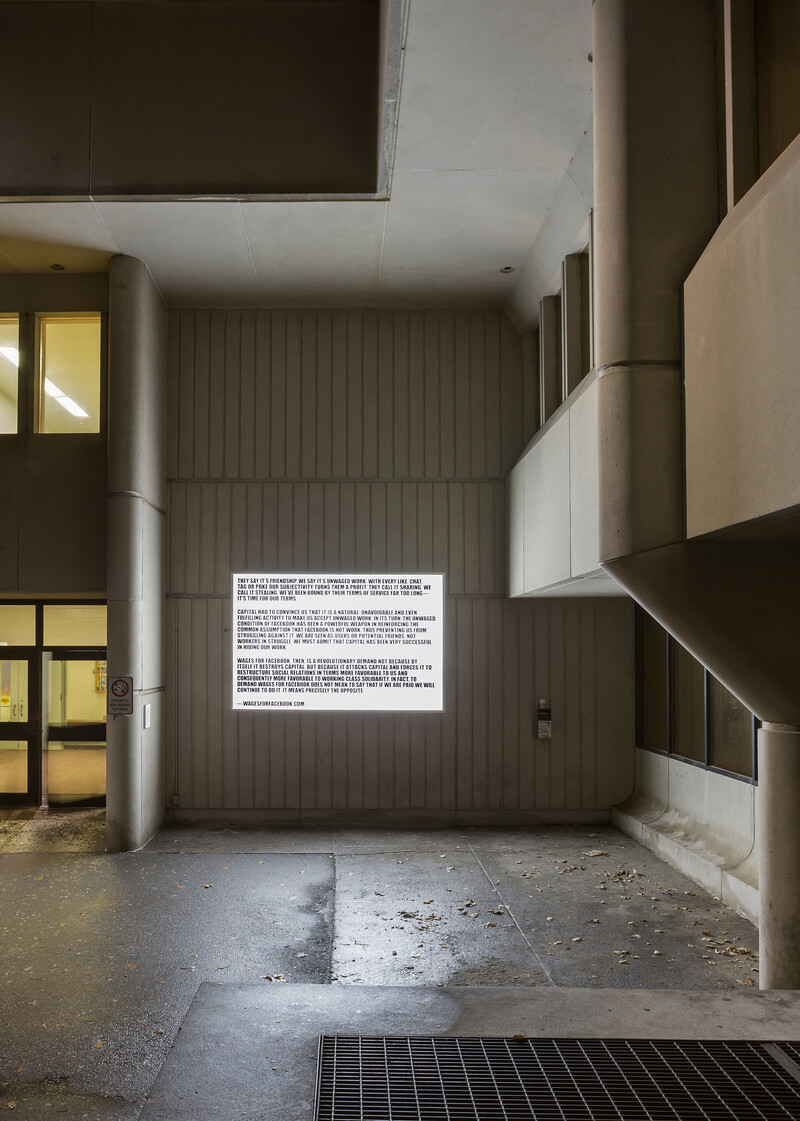

Excerpted text from the Wages For Facebook manifesto is presented on a backlit billboard as one element of a campus-wide campaign at the University of Toronto Mississauga which includes wallpapering the campus with speculative campaign posters; staging information tables staffed by (waged) Work-Study students; installing a digital labour reading room in the Hazel McCallion Academic Learning Centre; giving away free buttons that feature the motto WWWORKERS OF THE WORLD, UNITE!; flyering the campus with the text from hundreds of tweets discovered online voicing both support and criticism of Wages For Facebook; hosting a reading group on the politics and culture of social media; organizing a discussion-based workshop with Laurel Ptak on the political precedents for Wages For Facebook; and collectively exploring the possibility of building a workers’ centre on campus.

Wages For Facebook: Poll

Are you a Facebook user? Why or why not?

What do you mostly use it for?

How often do you update Facebook?

How does social media affect your interactions with other people?

Does social media feel like work to you?

Do you care that Facebook is making money off of your newsfeed?

Would being compensated for using social media change how and why you use it?

What type of Facebook work could logically be compensated?

What kind of governing body could represent workers of Facebook?

Are you interested in participating in the Wages For Facebook campaign? Why or why not?

This poll was conducted by students of the University of Toronto Mississauga, from October 6th to October 20th, 2014.

Project Statement

Wages For Facebook draws on the 1970s feminist campaign Wages For Housework to think through the relationships of capitalism, class, and affective labour at stake within social media today. Wages For Housework demanded that the state pay women for their unwaged housework and care-giving, as the market economy was built upon massive amounts of this unacknowledged work—and its labourers could be seen to constitute a huge working class. Wages For Housework built upon anticolonial discourse to extend the analysis of unwaged labour from the factory to the home. Along these lines, Wages For Facebook attempts to extend the discussion of unwaged labour to new forms of value creation and exploitation online. The launch of a manifesto website, wagesforfacebook.com, in January 2014 clearly hit a collective nerve. Since then the project has been debated widely via social media, at universities, and in the press, setting off a crucial public conversation about workers’ rights and the very nature of labour, as well as the politics of its refusal, in our digital age.

Project History

As soon as the website launched in January 2014 it was graced with over 20,000 views (and counting) and rapidly and internationally debated on social media platforms and message boards, as well as in mainstream and left press including The Nation, International Business Times, Dissent, The Atlantic, Jacobin, and The Hindu. It has been analyzed at conferences by academics across disciplines of geography, cultural studies, anthropology, public health, and labour; used to support the argument for Universal Basic Income by Pirate Party enthusiasts in Europe; spawned an activist group ready to collectivize and make the demand for wages for Facebook; is being taught to students in universities internationally; and is the subject of workshops and installations in the art context taking place in Chicago, London, New York, San Diego, San Francisco, and Stockholm. Wages For Facebook contributors and supporters include Eric Nylund, Michelle Hyun, Christina Linden, Anna Lundh, Pedro Neves Marques, Laurel Ptak, Mariana Silva, Christine Shaw, Nicole Cohen, as well as numerous University of Toronto Mississauga students, staff, and faculty.

Wages for Facebook

Part of the exhibition FALSEWORK, September 15 – December 7, 2014.

Curated by Christine Shaw

Installation Views

- Artist

- Laurel Ptak

- Curator

- Christine Shaw

Shaw’s work convenes, enables, and amplifies the transdisciplinary thinking necessary for understanding our current multi-scalar historical moment and co-creating the literacies, skills, and sensibilities required to adapt to the various socio-technical transformations of our contemporary society. She has applied her commitment to compositional strategies, epistemic disobedience, and social ecologies to multi-year curatorial projects including Take Care (2016–2019), an exhibition-led inquiry into care, exploring its heterogeneous and contested meanings, practices, and sites, as well as the political, economic, and technological forces currently shaping care; The Work of Wind: Air, Land, Sea (2015–2023), a variegated series of curatorial and editorial instantiations of the Beaufort Scale of Wind Force exploring the relentless legacies of colonialism and capital excess that undergird contemporary politics of sustainability and climate justice; and OPERA-19: An Assembly Sustaining Dreams of the Otherwise (2021–2029), a decentralized polyvocal drama in four acts taking up asymmetrical planetary crisis, differential citizenship, affective planetary attention disorder, and a strategic composition of worlds. She is the founding editor of The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Blackwood, 2018–ongoing), and co-editor of The Work of Wind: Land (Berlin: K. Verlag, 2018) and The Work of Wind: Sea (Berlin: K. Verlag, 2023).

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently closed, reopening March 27. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.