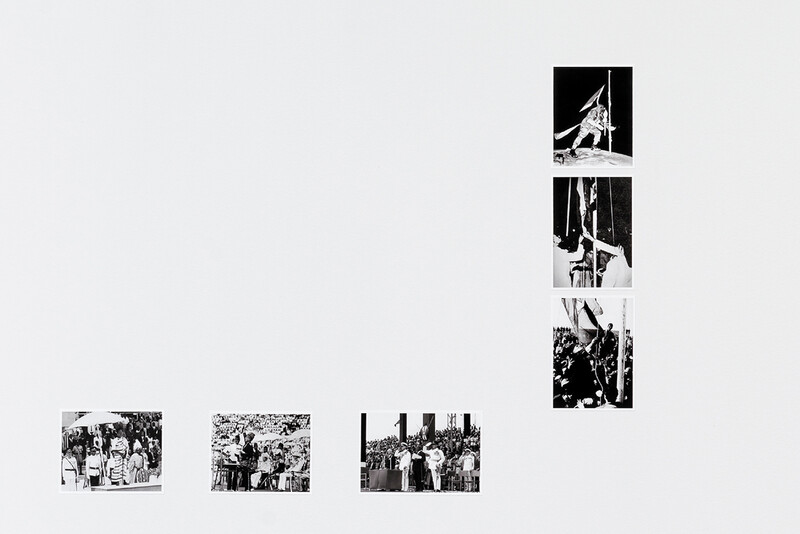

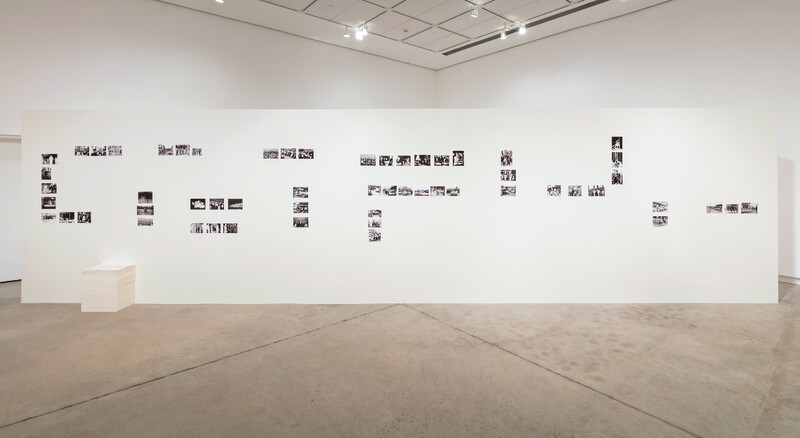

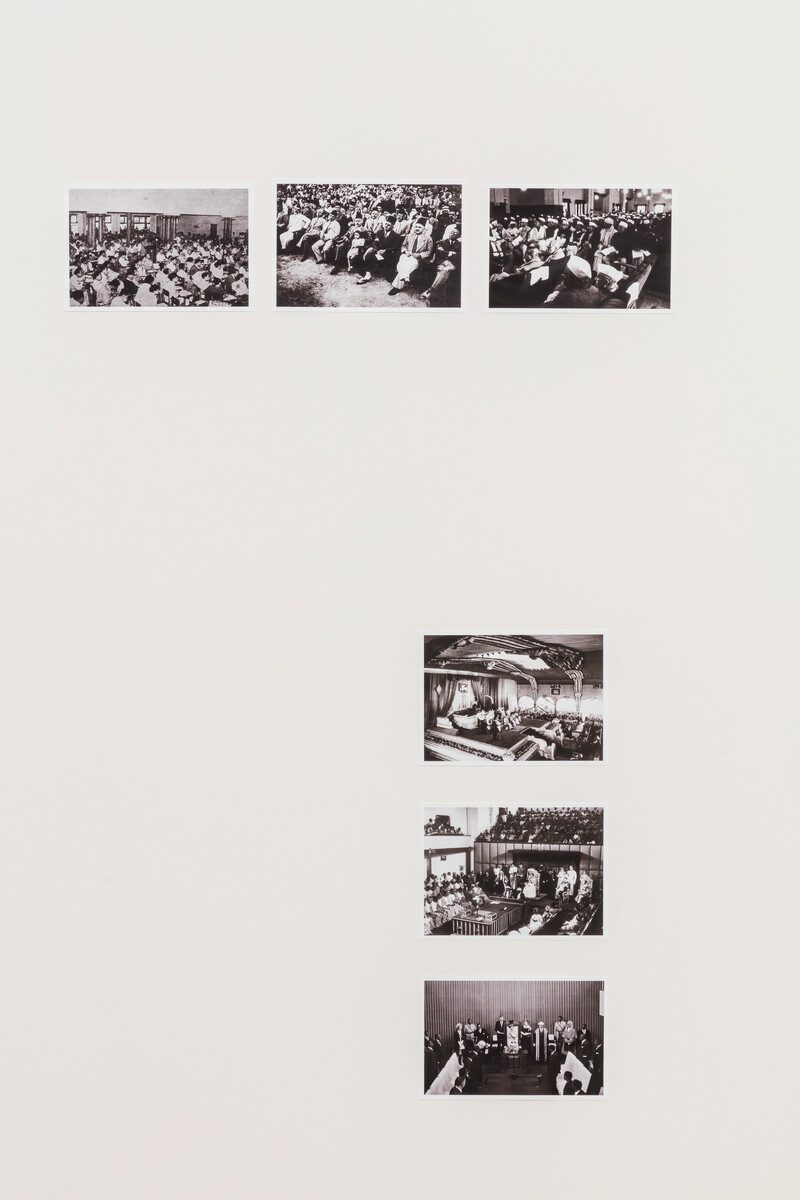

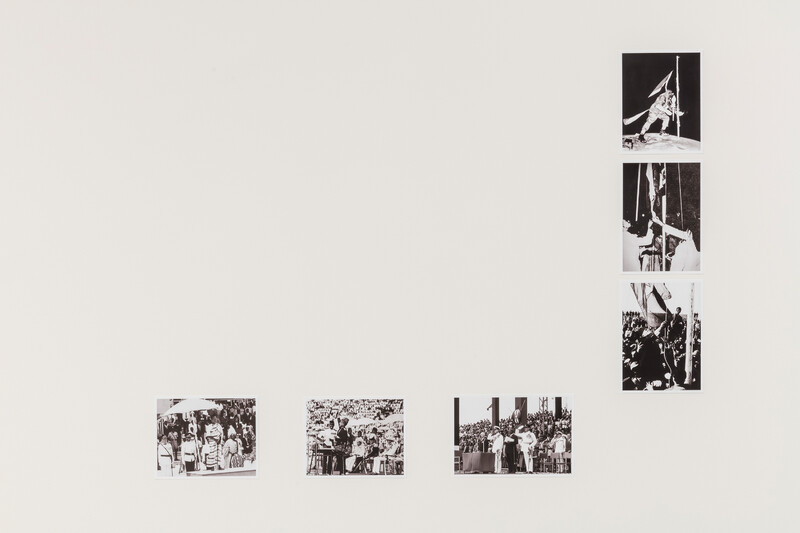

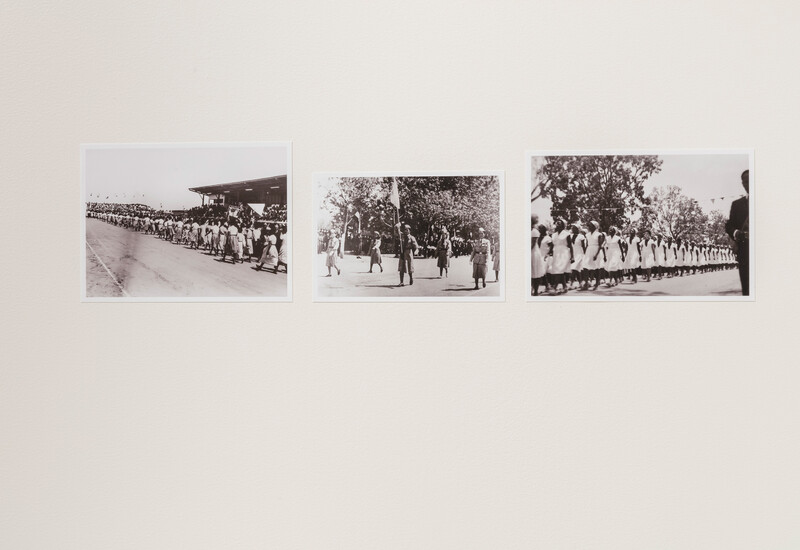

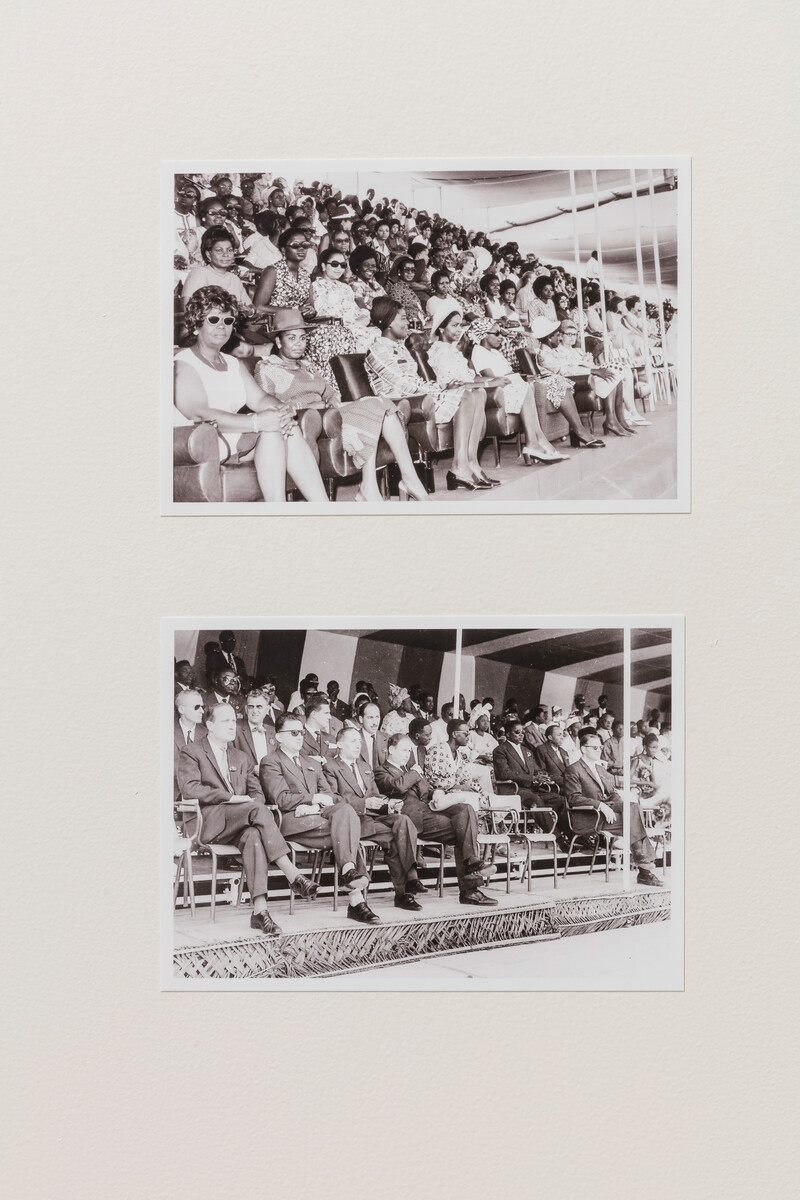

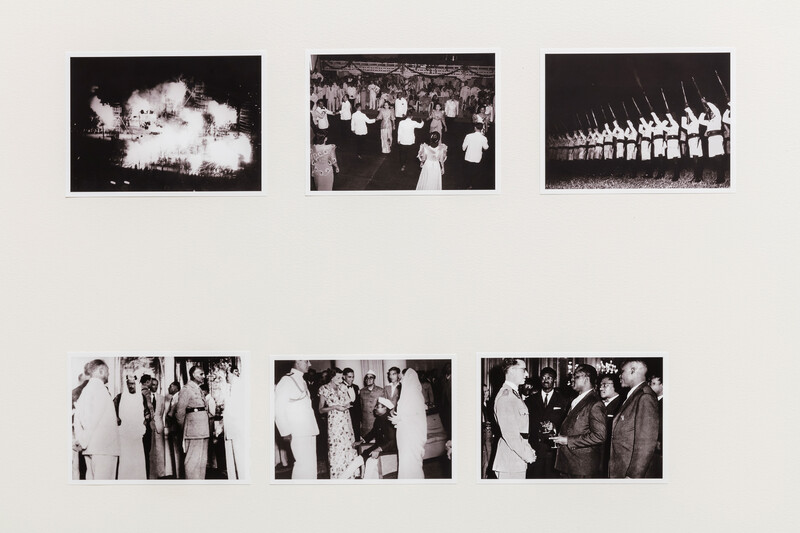

The Day After takes root in Maryam Jafri’s ongoing project Independence Day 1934–1975 (2009–present), an installation composed of photographs taken on the first independence day in former European colonies across Asia and Africa between 1934 and 1975. The photos are sourced from the countries themselves (in order to highlight, in the artist’s words, “how post-colonial states in Asia and Africa preserve the founding images of their inception as independent nations”) and display striking similarities despite disparate geographical and temporal origins, revealing a political model exported from Europe and in the process of being cloned throughout the world. The installation gathers images collected from 29 Asian and African archives, juxtaposed according to a specific grid around categories of events. In her arrangement, Jafri emphasizes the generic character of the rituals and ceremonies held during the 24-hour twilight period when a territory transforms into a nation-state. The grid, reminiscent of both photo-conceptualism and the storyboard medium, is broken, disturbing the ideological order at play in the images and suggesting non-linear readings.

The Day After takes this rare “second order archive”—or “collection of collections,” as Maryam Jafri calls it—as a starting point to question various artistic, historical, and political issues arising from these images and their historical and institutional background. What do we see when we look at the photographic depiction of an event? How is history framed by its representations? How are images and their significations affected by their context of circulation? How do visual symmetries and comparisons transform our understanding of the narratives arising from the days of independence and, by extension, the days after? And, backstage, what do conditions of access and preservation reveal about the stakes projected onto these photographs? To give a voice to stories in the margins of history’s official images and to the myriad relationships surrounding them, Bétonsalon proposed to Maryam Jafri the idea of bringing together a network of journalists, archivists, artists and researchers who helped her gather these images or whose work resonates with the issues raised above. The Day After seeks to focus on the peripheral context of the images gathered by the artist, so as to encourage varied perspectives and generate multiple histories. Conceived as a space of encounters and debates, the exhibition serve as a terrain of investigation to expand on some of the issues that emerged from Bétonsalon’s conversations with Maryam Jafri.

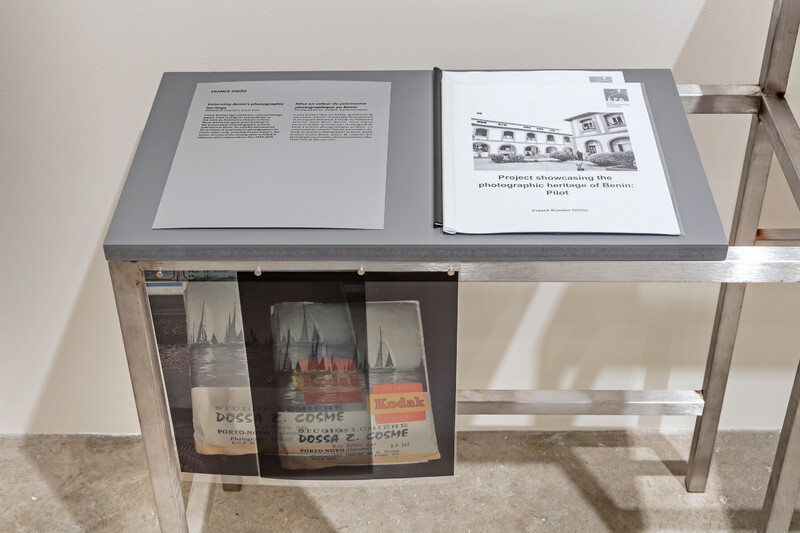

Thus a variety of materials (magazines, photographs, films, texts, as well as artworks) together form a companion to Independence Day 1934-1975. The contributions, emerging from the work of participants in the artist’s research over the last few years or invited by Bétonsalon and the Blackwood Gallery, seek to trigger a re-examination not only of the photographs themselves—the context in which they were produced and the historical narratives attached to them, as in the study by Madagasy historian Helihanta Rajaonarison who collected personal stories from inhabitants of Antananarivo at the moment of its independence and in so doing brought out other readings of official photographs; but also of their current status and the problems of conservation, such as those featured in the contributions of historian Erika Nimis (a specialist on Mali photography) and Franck Ogou (a lecturer at the School of African Heritage in Benin), highlighting property and international issues, as well as the subject of authorship and copyright, as addressed in another of Maryam Jafri’s works, Getty vs Ghana (2012); and finally of the geopolitical and cultural upheaval caused by the events they depict—debts imposed by European powers on their former colonies, the petrol crisis, the spread of Pan-African movements and the Non-Aligned movement (the Bandung conference was held in 1955), and the development of projects of identity and culture as discussed namely in magazines and film productions (the films of S.N.S. Sastry in India, for example) in the fifties and sixties.

Arranged throughout the exhibition like sculptures, the materials together trace a nonchronological journey, fragmented because subjective, and open to rearrangement and reassembly. They will thus be activated and recharged by the various interventions of researchers, students, and artists invited to interact with the exhibition during a series of events (seminars, performances, screenings, workshops, and visits) held in the Blackwood Gallery’s e|gallery and at the University of Toronto Mississuaga, or in collaboration with partner organizations in Toronto. This presents an opportunity to generate diverse new viewpoints, making the exhibition a constant “work in progress.” With The Day After, we aim to catalyze the many studies linked to issues raised by the exhibition in Canada and abroad, and provide a visible space for them to intermingle, thus uniting and strengthening positions while eliciting unexpected dialogue.

“Not only is it impossible to reduce photography to its role as producer of pictures,” theorist Ariella Azoulay reminds us, “but [...] its broad dissemination over the second half of the 19th century has created a space of political relations that are not mediated exclusively by the ruling power of the state and are not completely subject to the national logic that still overshadows the political arena. This civil political space [...] is one that the people using photography—photographers, spectators, and photographed people—imagine every day.”1 It is to this political exercise of an imaginative gaze that The Day After invites us.

The Day After

Curated by Mélanie Bouteloup and Virginie Bobin

Conceived by Bétonsalon – Centre for art and research, Paris, France, and co-produced by Tabakalera, San Sebastián, Spain.

Events

Installation Views

- Artist

- Maryam Jafri

Previous solo exhibitions include Kunsthalle Basel, Bétonsalon (Paris), Gasworks (London), Bielefelder Kunstverein (Bielefeld), Galerie Nova (Zagreb), Beirut (Cairo), the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (Berlin), and Malmö Konst Museum (Malmö). Her work has also been featured extensively in international group exhibitions, including at Beirut Art Center, 21er Haus (Vienna), Institute for African Studies (Moscow) and Contemporary Image Collective (Cairo) in 2015; Camera Austria (Graz), Contemporary Art Gallery (Vancouver), CAFAM Biennial (Beijing), Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami (Miami) in 2014; Museum of Contemporary Art (Detroit), Mukha (Antwerp), and Blackwood Gallery (Mississauga) in 2013; Manifesta 9 (Genk), Shangai Biennial, and Taipei Biennial (Taipei) in 2012, among others. She was an artist-in-residence at the Delfina Foundation in London in 2014, as part of the program The Politics of Food. In 2015, she was a part of the Belgian Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennial and the Götenburg Biennial. She lives and works between New York and Copenhaghen.

- Curators

- Mélanie Bouteloup & Virginie Bobin

Hadrien Gérenton

With contributions by Jean Genet, Kapwani Kiwanga, Helihanta Rajaonarison, S.N.S. Sastry, and Jürg Schnieder, and students and researchers from the University of Toronto.

The Blackwood Gallery is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Department of Visual Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga.

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently closed, reopening March 27. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.