It would probably be a better world if we didn’t use colour terms at all to designate groups of people. Failing that, it might well be better if we used other terms, like pink, olive, and grey to refer to what we now call white people, partly because they are less loaded, partly because this would break up the monolithic identity, whiteness.

—Richard Dyer, 19971

Red, Brown, Yellow, Black, White: all colours used to describe people, somewhat contentiously, of culturally diverse backgrounds. The colourism, or discrimination based on skin colour (of even those of the same skin colour), that Dyer describes is what inspired me to examine the relationship between race and colour.2 In order to present a subtler approach to this fraught territory, I opted to investigate the formal qualities of colour through colour theory. However, the selected works also allow us to consider different ways in understanding race for they stage their formal elements in performative ways which engage the public and thereby foster a reflection (in both senses of the word) on the politics of colour.

“What is that I really see here? I see a bit unclearly in the picture, but in person I can see much better” with these words from Kika Nicolela’s video, I began my process. By asking myself how do I read and interpret works, I delved deeper in my ongoing research on the politics of identity, race, and performativity. Using strategies developed in previous curatorial experiences, I first focused my efforts on including a diverse range of artists in an attempt to present underrepresented groups—artists who each fulfilled a coloured niche. But I soon realized that this offered an all too quick resolution as it reaffirmed the classification of races by colour terms. To include or exclude an artist based on their cultural background was absurd and had become counterintuitive. This led me to instead examine colour through the frames of reference offered by vision and colour theory. My practice as a performance artist informs how I engage with exhibitions, live performances, and conversations; correspondingly, this perspective has coloured the development of this exhibition. Interested in the viewers’ active engagement with the works, I view the performative as an enactment, either through live action, performance for documentation, or by the viewer’s engagement with the works. The works included in Red, Green, Blue ≠ White share a sensibility for subtle performative gestures; the marking of bodies through various means, the construction of identities through cosmetics and clothing, and the critique of white—white, the colour and the race.

Aryen Hoekstra’s Out of Focus (RGB) (2013) ironically both refutes and confirms the title of the exhibition. Three slide projectors devoid of slides beam light through a coloured filter whilst continuously auto-focusing. The red, green, and blue beams are positioned to converge into a rectangular field—a white or ‘non-image’ is thus created that represents the absence of colour. Upon further reflection however, one notices that the three beams result in a field of impure white; a not quite white. When a viewer intercepts the projection throw, incidental colours are created because in instances when two primary colour sources overlap coloured silhouettes of yellow, red, green, pink, etc. appear which mark the body of the interceptor. In this gesture, the body acts similar to a prism—when the white light meets the body, a multitude of coloured refractions result.

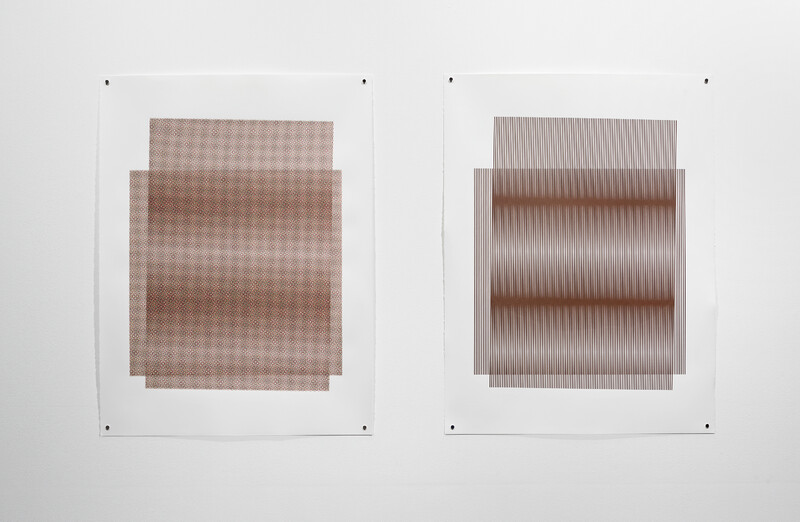

Brown Study Colour Line (2011) by Kristina Lee Podesva presents an analogous approach to an absolute, here we shift from pure white to melange brown. Brown is a mixture of all paint colours, and has no place nor opposite on the colour wheel. Akin to Hoekstra’s work, Podesva’s serigraph diptych employs the layering of colours in the CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black) process of printing to create another—an other that becomes an inextricable mix or blend. Perspectives change as the viewer nears the work, at first glance, the two serigraphs seem matched in colour, but upon closer inspection one serigraph is composed of small distinguishable circles of cyan, yellow, magenta, and black, whereas the other serigraph is resolutely one brown layer. This dual composition muddies the colourist’s aspirations for clearly delineated differences, for brown is the inevitable resulting composition of the mixture of all colours. Tempered by hues, brown represents the end product of the colour field. It blends and blurs the lines between race, thus causing a constant re-focusing. Colours in fact can shift from one to an other, they are performative agents.

Consisting of instructions, black ink, paintbrushes, tweezers, and two bowls—one full of white rice, and the other empty, the viewer is invited to enact a gesture. Chun Hua Catherine Dong’s installation, titled Hourglass (2010), instructs the viewer to select and paint a grain of white rice black, then place it into the adjacent, empty bowl. This repeated action contributes to the tracking (and passing) of time, and allows for meditation on the symbolism of this gesture. The gesture of painting white rice to black renders the food inedible and the product becomes an archive of the action and marker of time. The whiteness of the rice represents the absence of colour, whereas the ink contrasts this with its opposite. David Batchelor defines chromophobia as the fear of corruption through colour, which is interpreted as dangerous and alien.3 Dong sets up this gesture to embrace not just colour, but the darkest colour as a performative metaphor for the shifting power relations between the West and the rest.

The activation of accumulation and the liveness of colour are recurring themes in the exhibition, from the growing pile of black rice, to Golboo Amani’s and Manolo Lugo’s Covergirl (2012). In this three hour durational live-performance, the artists will conceal each other’s faces with all the available hues of Covergirl foundation. From ‘ivory’ to ‘normal beige’ to ‘tawny’, each hue is purged from the face with a white handkerchief that is then displayed as a specimen for inspection within the gallery space.4 The specimens contain a ghost-like quality similar to that of the Shroud of Turin, they represent an indexical trace of each artists’ face. Foundation make-up professes to enhance beauty by masking imperfections; this gesture also conflates the gender of the artists as they mimic one an other and blur their individual identities. Furthermore, the homogenous hues problematize race since the available spectrum tellingly excludes darker complexions.5

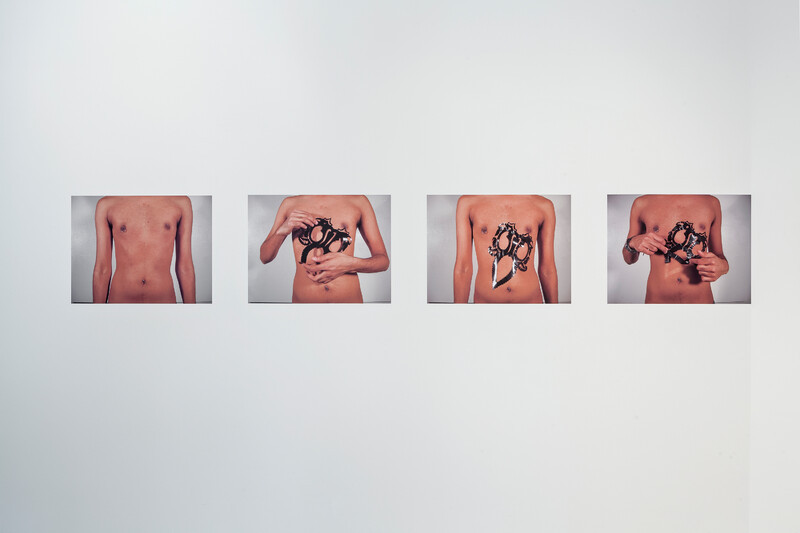

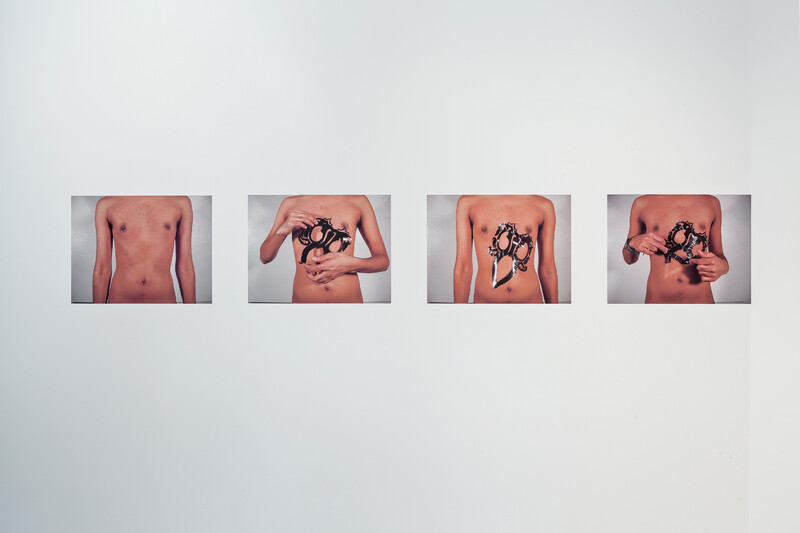

As a Kenyan-Indian-Canadian, Brendan Fernandes reclaims his cultural hybridity through the act of tanning. Changing to Summer (2005) documents the gradation of the artist’s skin as textile motifs are emblazoned onto his body. With the paisley decals layered on top of each other, he then exposes his torso to UV tanning lights which render his skin into a range of different tones and shades. This is a figurative attempt to reconcile his identities and hold on to his cultural histories. A tan, viewed by some with negative connotations of the working class and manual labour, here becomes a positive reclamation of the artist’s body and multicultural heritage.

The exhibition includes a second work by Chun Hua Catherine Dong titled After Olympia (2011). This photograph documents a three hour durational performance where the artist cleansed a white male subject’s body with rubbing alcohol before meticulously licking his whole body. The title references Edouard Manet’s infamous painting Olympia (1863) and by extension the history of Western European Art and the tradition of objectifying the female body in paint. The artist comments on power relations as she subverts the original painting’s gendered composition. Dong stands in as an authoritative, medical figure instead of the black female ‘Negress’ archetype in the referenced 19th century painting. In addition, a submissive, languid, white male body replaces the confrontational courtesan that the painting was named after. Dong marks the subject’s body with her saliva, leaving a trace of herself and her dominance over the male figure. The tables are turned, at least temporarily. The licks literally embody language, they claim language and thereby control. Their measured sensuality is empowered and empowering.

Re-claiming power is paramount to critiques of colourism, but ambiguity can also be constructive. In self-portrait in alterNation between descension & ascension (2010), the single-channel video captures the artist Jude Norris’ in perpetual motion, yet stationary in elevation. Wearing a plains-style deer hide dress and regalia, the ‘Sohkatisiw Iskwewasakay’ or Strong Woman Dress appears disjunctively traditional and archaic in contrast with the urban setting of an escalator and flanking staircases of the Brooklyn Library. Stepping upwards and downwards on an escalator, Norris is stuck in a mesmerizing limbo between two planes, symbolic of spiritual movement and the rigidity of stereotypes about First Nations People. The artist negotiates her identity as Métis (Cree/Anishnawbe/Russian/Scottish Gypsy) of the Plains Cree affiliation, and through this treading action her head is continually bobbing above the centre of the frame (the horizon) as she navigates staked racial territories.

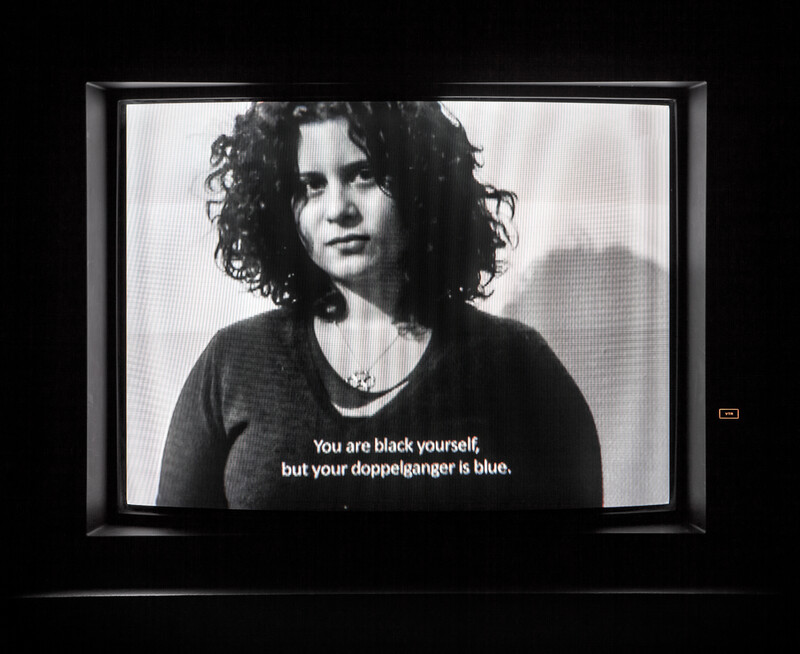

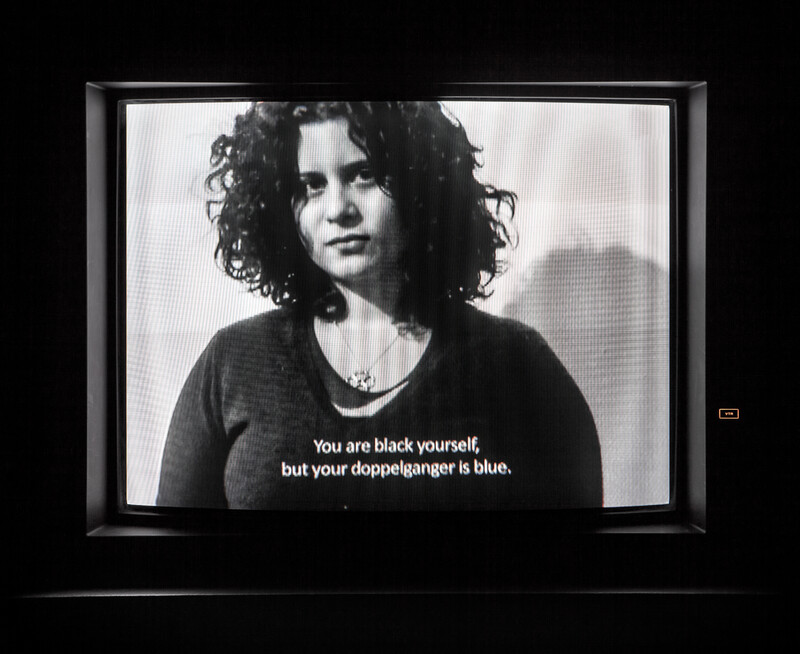

An awkward smile, yet receptive body language was my initial reading of “What do you think of me?” (2009) by Kika Nicolela. I was drawn to the use of language in relation to colour and wanted to contextualize her work within a larger conversation around race and identity. “What do you think of me?” is the initiating and only question posed to gallery goers in Finland featured in the video. As these gallery goers hold the camera, they describe the artist, commenting in their native tongue; these responses are the first impressions of the gallery goers as they become active participants in the work. The result for the viewers of the video is a heightened awareness of the stakes of difference between the camera-wielding gallery goers and the artist as the former focus on the physical characteristics of the latter. Using descriptors such as "coffee," "licorice hair," "sunshine face," and "carnival," Finnish locals make assumptions about her cultural heritage and racialize her body—all this, due to the language barrier, is unbeknownst to the artist.

One could posit that white has been the dominant colour in most domains, including art. White is a predominant hue for skin tones in painting and the symbol of the Enlightenment.6 This is indicated by the tradition of using ceruse, or white lead, and powders, to cover and whiten one’s skin as a symbol of status, perpetuating the correlation between whiteness (both race and colour) and beauty.7 Through the mixture of paint, the accumulation of light, the layering of inks, the application of make up, the works selected for this exhibition highlight the formal qualities of colour as a means to understand race and the construction of identity and thereby debunk colourist readings of people. The performative elements of the works instill shifts in the relationship between the viewer’s body, vision, and consequent understanding. The symbol ‘≠’ fosters a conversation about race, extending from an awareness of inequalities to the artistic presentation of shifting perspectives.

—Johnson Ngo, Curator-in-Residence

Red, Green, Blue ≠ White

Curated by Johnson Ngo

Artist Projects

Lightbox Commission

Events

Installation Views

- Artists

- Golboo Amani

- Manolo Lugo

- Chun Hua Catherine Dong

- Aryen Hoekstra

- Brendan Fernandes

- Kika Nicolela

- Jude Norris

- Kristina Lee Podesva

and photography. She has participated in over 100 solo and collective exhibitions internationally, in institutions including the Museum of Image and Sound (São Paulo), MASP (São Paulo), Museum of Modern Art (Buenos Aires), KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Berlin), Museum Ludwig (Cologne), LOOP Gallery (Seoul), GL Strand (Copenhagen) and Parc de La Vilette (Paris). In 2010, she had a retrospective of her videos at the Museum of Modern Art in Salvador, Brazil.

kristinaleepodesva.com

- Curator

- Johnson Ngo

Generous supported by the Canada Council for the Arts, the Jackman Humanities Institute, the Toronto Reel Asian International Film Festival, University of Toronto Student Housing & Residence Life, and Open Studio.

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently open. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm, Wednesdays until 8pm.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.