The land is marked by ephemera from our actions and active existence. Markings of our histories, knowledge systems, homes and activism are present and leave imprints on the landscape. We, as Indigenous peoples, continue to create an ongoing narrative about our bodies’ connections to the land, regardless of past and present colonial attempts of displacement from our communities and the lands we are connected to. This image set, Living Memories, aims to acknowledge the Indigenous body and the actions it takes as a site and method of expression, examining the physical presence of Indigenous peoples with and on the land.

Living Memories features images by collaborators Asinnajaq and Camille Georgeson-Usher, and Sydney Frances Pickering. Each artist’s work documents performative actions that took place on remote land not easily accessible to large public audiences. These living works are meant to be witnessed over time by those who unexpectedly come across them, inviting the viewer to spend time and to reflect on how structures, documents, and markings are made—and who left them behind. These images convey histories of forced removal, the displacement of peoples, Indigenous placemaking, and the building of temporary structures meant to live and die in nature. Collectively, the images question how we as Indigenous peoples interact with and leave our legacies on the land.

As a set, Living Memories acts as an open invitation for deep(er) listening, and for reflection on the marks that living memories make on the land. In each of the works something is left on the land that is not meant to be permanent; rather, these marks are meant to live and leave traces that will eventually decay or disintegrate over time. These ephemeral markings are layered, left through generations of people moving through and living on the land. These artists’ images animate questions like: How do we witness and experience our histories? What does presence teach us about absence?

—Becca Taylor

Image Set

unearthed

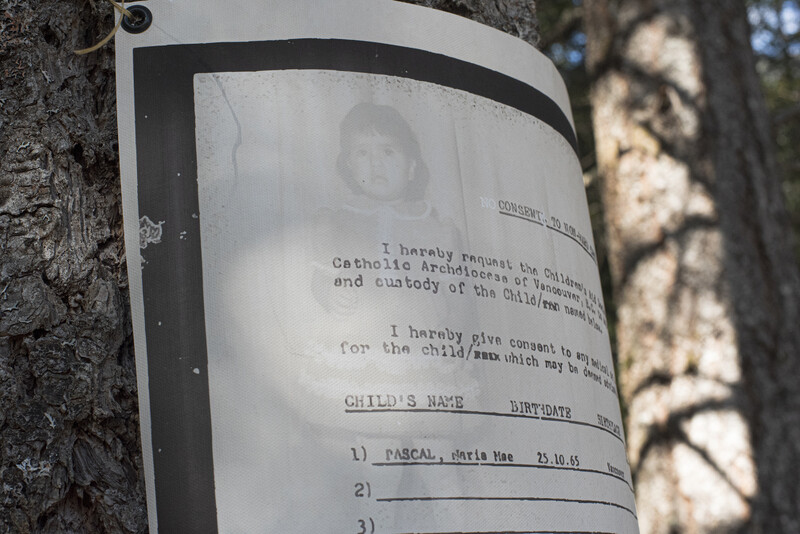

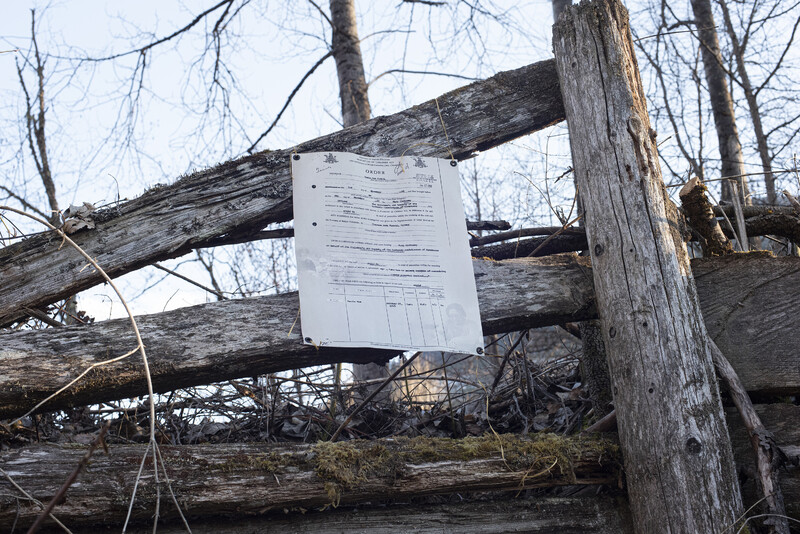

In the image unearthed, Sydney Frances Pickering shares family documents from the Sixties Scoop class action lawsuit authorized by the Catholic Archdiocese of Vancouver, of which her grandmother and mother were a part. The “Sixties Scoop” refers to the unauthorized and coerced removal of Indigenous children from their families and band without consent, placing them in the foster care system or adopting them into primarily non-Indigenous families. These actions affected many adoptees' sense of cultural identity and created emotional and physical separation between child, parent, siblings, relatives, community, language, and territory.

In unearthed, Pickering alters the legal documents by layering family photographs of her mother as a youth to humanize their officiousness, placing her mother within the same page that sought to permanently sever familial relations. The original document shows the ways in which the English language has been used as a representation of false realities; a tool, a weapon, to carry out the intentions of a system of forced removal and separation between parent and child. These documents and the English language have and continue to be used as a source of power and manipulation against Indigenous peoples and their relationships to family, community and to land.

To extend this gesture, the altered documents seen in the series have been returned to and documented in her mother’s traditional territory in Lil’wat Nation in relation to sites of importance to her family's histories and futures. In unearthed, Pickering honours the strength of her late kwékwa7 Theresa Attsie Pascal whose perseverance brought her family back home to this site, resisting the permanence of the Sixties Scoop’s intentions for forced removal.

this world, here; nesting

Asinnajaq and Camille Georgeson-Usher’s collaborative work, this world, here; nesting, shows the construction of a lifesize nest made of grasses, leaves and surrounding flora found in Northern Alberta. Sitting on top of an old railroad track, the nest is big enough for two people to sit comfortably in it, in a pathway beside a small lake that is well-travelled by locals as well as visiting artists for the land-based residency program common opulence that is hosted there. The nest is an invitation to sit listening deeply to the land, to connect profoundly and to witness the stories it has to share with us.

The nest is not intended to be a permanent structure, but something that lives and dies within the landscape, to be witnessed only in its temporary existence. These tender acts of love and care in building the nest are an extension of Asinnijaq and Georgeson-Usher’s collaborative practice, in which they often examine the nurturing qualities and generative possibilities of inter-connectivity—inter-connectivity that calls for shared moments of active listening and witnessing with one another, our communities, our ancestors, future generations, and the land. These moments are abundant with shared memories, histories, understandings, and knowledge, and are an opportunity to pause and to collectively imagine our future.

See Connections ⤴

Camille Georgeson-Usher is a Coast Salish/Sahtu Dene/Scottish scholar, artist, and writer from Galiano Island, British Columbia. Usher completed her MA in Art History at Concordia University. Her thesis, “more than just flesh: the arts as resistance and sexual empowerment,” focused on how the arts may be used as a tool to engage Indigenous youth in discussions of health and sexuality. She is a PhD candidate in the Cultural Studies department at Queen’s University and was awarded the Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarship for her research-creation work looking at ontologies of gathering in urban centres. She was awarded the 2018 Canadian Art Writing Prize and most recently has exhibited work in Soundings: an exhibition in five parts. Usher is the Executive Director of the Indigenous Curatorial Collective, a Board Member of Artspace in Peterborough and the Toronto Biennial of Art, and part of the curatorial team for MOMENTA 2021.

See Connections ⤴

Sydney Frances Pickering is a member of Lil’wat nation. She is currently living and working on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish), and səl̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples. Her multidisciplinary practice includes hide tanning, video, sound, beadwork and poetry. She uses her practice to tell her family’s story, speak about identity, and what it is like to navigate as an Indigenous person within a colonial society. Her work over the past few years is grounded by her continued connection to land-based material practices.

See Connections ⤴

Living Memories

Sydney Frances Pickering

Curated by Becca Taylor

Part of Crossings: Itineraries of Encounter, the 2021–22 Lightbox Program

Image Set

Programs

Installation Views

Interpretive Video

Educator-in-Residence Shalon T. Webber-Heffernan leads a tour of Living Memories on University of Toronto Mississauga campus.

- Respondent

- Cheyenne Rain LeGrande ᑭᒥᐊᐧᐣ

- Attunement Session

- Kateri Gauthier

- Curator

- Becca Taylor

Notably, Taylor co-curated the 4th iteration of La Biennale d’art contemporain autochtone (BACA) with Niki Little, entitled níchiwamiskwém | nimidet | my sister | ma sœur (2018), co-led the land-based residency, Common Opulence (2018) in Northern Alberta, and curated Mothering Spaces (2019) at the Mitchell Art Gallery. Taylor is currently the Director of Ociciwan Contemporary at Centre, a collective run art centre in amiskwacîwâskahikan that focuses on supporting Indigenous contemporary Art.

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are currently closed.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.